The Monroe Doctrine, whose 200th anniversary is marked this year, has been the subject of countless articles in the press. Many argue that the foreign policy position announced by President James Monroe in 1823 was a declaration of “imperialist” designs on Latin America, and that Washington’s course today is simply a continuation of that policy.

That explanation is false. It blurs together different historical periods. To understand where we came from and where we are going, working people need to study the history — the concrete conditions and evolution — of the conflict between class forces that has driven U.S. and world politics.

Today we live in the imperialist epoch. But we can’t look at history through 21st century eyeglasses. When the United States was established as a republic in the late 1700s, capitalism was on the ascent. It was the most progressive social system the world had ever seen — a revolutionary advance over outmoded feudalism, which had prevailed for centuries.

As capitalist trade, agriculture, industry, transportation and communications were revolutionized and spread worldwide between the 15th and 19th centuries, humanity’s productive capacities multiplied more than during all its previous existence put together.

Most importantly, capitalism created the working class — the only class that has the capacity and material interest in leading a successful struggle to replace the rule of the propertied, exploiting classes with a society organized in the interests of the vast majority.

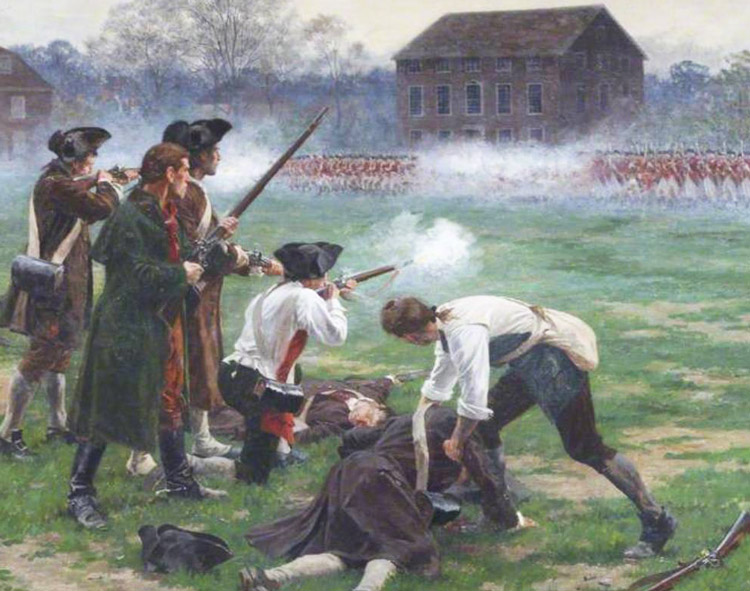

The United States was born through a deep-going popular revolt. “The history of modern, civilized America opened with one of those great, really liberating, really revolutionary wars,” Russian revolutionary leader V.I. Lenin explained in his 1918 “Letter to American workers.”

“That was the war the American people waged against the British robbers who oppressed America and held her in colonial slavery.”

Over the first half of the 19th century, the U.S. developed rapidly, expanding coast to coast. The 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the 1846-48 war with Mexico, and the 1846 Oregon Treaty were all part of securing for the American capitalists the land, waterways, ports and internal market that helped consolidate a modern bourgeois nation.

From a historical perspective, this process was in the class interests of working people. Only the most thoroughgoing development of capitalism could bring about such a vast expansion of productive forces and put the working class in the strongest position to lead the next historic battles to advance humanity. A more in-depth explanation of this dynamic can be found in the book Labor, Nature, and the Evolution of Humanity: The Long View of History, by Frederick Engels, Karl Marx, George Novack and Mary-Alice Waters.

Another leap forward took place with the Second American Revolution — the 1861-65 Civil War, which overthrew chattel slavery, followed by Radical Reconstruction. By its end, Karl Marx wrote that he could see the social forces that would lead the next American revolution — the developing working class, exploited Western farmers and the oppressed Black population.

The U.S. became the most politically advanced nation in the world. Marx, co-founder with Engels of the modern revolutionary workers movement, called it the “great Democratic Republic.” The Bill of Rights, added to the U.S. Constitution as a result of struggles by farmers and workers after the First American Revolution, contained democratic protections beyond any recognized in Europe: freedom of speech and assembly, separation of church and state, freedom of religion, the right of citizens to bear arms, and freedom from arbitrary search and seizure, among others.

European colonial threat

Now let’s take a look at where the Monroe Doctrine fits into this history.

In an 1823 message to Congress, Monroe warned European powers that Washington would not tolerate any “future colonization by any European powers” or interference against “governments who have declared their independence” in the Western Hemisphere. There was good reason for this concern.

Despite what some opponents of U.S. imperialism argue today, the biggest threat to struggles for independence and sovereignty in Latin America and the Caribbean through most of the 19th century was not the United States. It was the European powers — especially the British rulers.

The British Empire continued to interfere with the sovereignty and economic independence of the fledgling United States. That led to the War of 1812, and then to London’s support to the Southern slaveholders in the U.S. Civil War.

The British rulers flexed their muscles throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, seeking to replace Spain — which lost most of its American colonies between 1810 and 1825 — as the dominant power.

Eduardo Galeano, in his classic book The Open Veins of Latin America, describes how British bankers and merchants dominated South America’s export market — Chilean copper, Peruvian nitrates, Brazilian coffee, Argentine beef. British and French warships blockaded Buenos Aires in 1845 to try to open up Argentina to unrestricted imports of European goods.

Monroe Doctrine

In 1822 the Monroe administration recognized the new republics of Chile, Argentina, Peru, Mexico and Colombia, and soon after, the newly independent Central American Federation.

In Europe, however, a reactionary coalition of the Austrian, Prussian and Russian monarchies — the “Holy Alliance” — had defeated Napoleon’s armies and was making clear its determination to wipe out all vestiges of the French Revolution and threats of republican rule. They were also concerned that the French invasion of Spain had weakened the Spanish crown and spurred the independence wars in its New World colonies. The Holy Alliance began preparations to back renewed efforts by Spain’s Bourbon monarchy to subjugate insurgent Latin America.

That was the context for Monroe’s warning to the European powers not to interfere in the affairs of newly independent Latin American nations.

Today, some opponents of Washington’s policies assert that U.S. “imperialism” has been seeking to conquer Latin American territory since the founding of the U.S. But that’s not accurate.

Prior to the U.S. Civil War, small groups of American adventurers organized armed expeditions to Mexico, Central America and Cuba. They sought to grab land for U.S. Southern slaveholding interests. The most notorious was William Walker, who landed in Nicaragua in 1855, proclaimed himself president, and declared slavery legal there, until he was driven out in 1857 by the united Central American armies.

Such adventures were historically doomed to fail — as was the Confederacy’s war of conquest to establish a reactionary slave empire extending into the Caribbean.

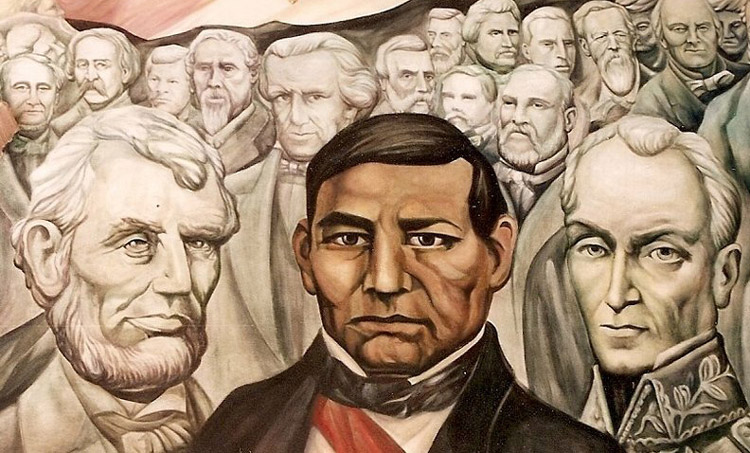

Lincoln and Benito Juárez

The best illustration of the progressive character of the Monroe Doctrine took place during the Second American Revolution. It was the response by President Abraham Lincoln’s administration to the French invasion and occupation of Mexico.

In 1861, the Mexican government of Benito Juárez, after winning a revolutionary democratic war against the power of the semifeudal landholding classes and Catholic Church hierarchy, declared a two-year moratorium on onerous foreign debts. In response, the British, Spanish, and French governments launched a joint military intervention against Mexico, which Marx denounced as a “new Holy Alliance.” Their goal was not only to make Mexico pay the debt, but to prop up reactionary class forces there and regain a foothold in the Americas. It was also part of efforts by the European powers to aid the U.S. slavocracy in the Civil War.

Although the British and Spanish governments backed out of the adventure, the French regime of Napoleon III carried through the invasion and installed Austrian Prince Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico.

The Lincoln administration backed the Juárez government and opposed the French-led war on Mexico, a clear violation of the Monroe Doctrine. Union Army generals Ulysses Grant and Philip Sheridan massed 50,000 troops near the Texas-Mexico border and transferred weapons to Juárez’s forces.

After the victory of the North in the Civil War, some 3,000 Union Army veterans joined and fought in Mexico’s republican army. And in U.S. cities from San Francisco to New Orleans, groups called Defenders of the Monroe Doctrine and the Society of Friends of Mexico held public meetings to promote solidarity and recruit volunteers for the Juarista army. By 1867, Juárez’s forces expelled the French invaders, a revolutionary victory celebrated annually as Cinco de Mayo.

It’s no surprise that José Martí, leader of Cuba’s independence struggle against Spanish rule, wrote in 1889, “We love the country of Lincoln as much as we fear the country of Cutting.” Francis Cutting was a leader of the American Annexationist League, which agitated for Washington to seize Cuba from Spain.

Martí was contrasting his admiration of the bourgeois-revolutionary heritage of the U.S. with Washington’s transformation, then underway, into an imperialist power.

What Lenin and Sankara explained

It’s Lenin, in his 1916 pamphlet Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, who best described how world capitalism had outlived its progressive character. He explained that imperialism is marked by the domination of finance capital, the rise of monopolies, and the division of the world among the big capitalist powers.

Lenin pointed to the 1898 U.S. rulers’ war against Spain over its colonies — Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam — as the first war of the imperialist epoch.

Imperialism, Lenin noted, is not a policy that a government chooses. The drive toward war and plunder is inherent to imperialism. It can only be ended by organizing a revolutionary movement of workers and farmers to take state power and overturn capitalist rule.

In taking a historical materialist approach to understanding developments like the Monroe Doctrine, we can also learn from Thomas Sankara, the outstanding communist and leader of the 1983-87 popular revolution in Burkina Faso.

“Our revolution in Burkina Faso,” Sankara said in a 1984 speech, “draws inspiration from all of man’s experiences since his first breath.” We “draw the lessons of the American Revolution, the lessons of its victory over colonial domination and the consequences of that victory. We adopt as our own the affirmation of the Doctrine whereby Europeans must not intervene in American affairs, nor Americans in European affairs. Just as Monroe proclaimed ‘America to the Americans’ in 1823, we echo this today by saying ‘Africa to the Africans,’ ‘Burkina to the Burkinabè.’”

Sankara saluted the powerful legacy of the French Revolution of 1789, the 1871 Paris Commune and “the great revolution of October 1917” led by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Russia.

We are, Sankara said, “the heirs of all the world’s revolutions.”