Malcolm X Talks to Young People is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for December. The book contains an interview and four talks given to young people in Ghana, the U.K. and the United States in the last months of his life. On Feb. 21, 1965 — 10 days after the final talk in this collection, presented at the London School of Economics — Malcolm was assassinated as he was speaking to an Organization of Afro-American Unity meeting at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. Socialist Workers Party leader Jack Barnes said Malcolm had increasingly become an authentic voice of the coming American revolution. Below are excerpts from the preface. Copyright © 2002 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

Malcolm X seized every occasion to talk to young people. All over the world, it is “young people who are actually involving themselves in the struggle to eliminate oppression and exploitation,” he said in January 1965, responding to a question from a young socialist leader in the United States.

They “are the ones who most quickly identify with the struggle and the necessity to eliminate the evil conditions that exist. And here in this country,” he emphasized, “it has been my observation that when you get into a conversation on racism and discrimination and segregation, you will find young people more incensed over it — they feel more filled with an urge to eliminate it.” …

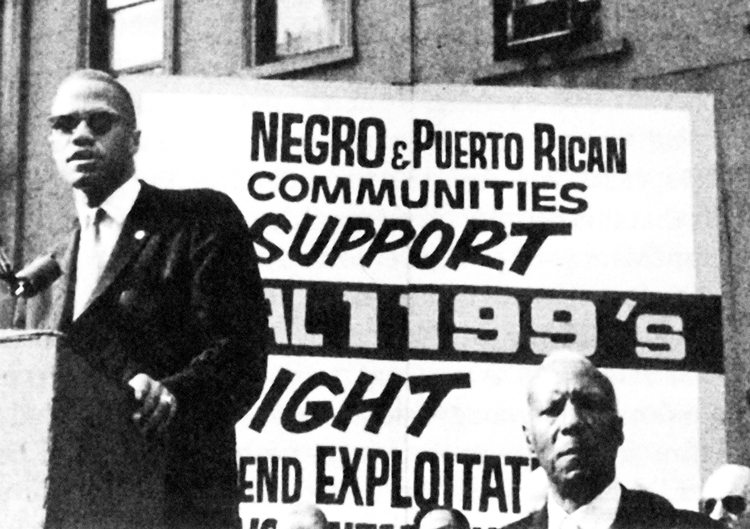

By the opening of the 1960s, Malcolm was politically drawn more and more toward the rising struggles by Blacks and other oppressed peoples in the United States and around the world. He used his platforms in Harlem and Black neighborhoods across the country, as well as on dozens of college campuses, to denounce the policies of the U.S. government both at home and abroad. He campaigned against every manifestation of anti-Black racism and was outspoken in condemning the pillage and oppression of the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America for the profit and power of the U.S. and other imperialist regimes.

“The black revolution is sweeping Asia, is sweeping Africa, is rearing its head in Latin America,” Malcolm said in a November 1963 talk to a predominantly Black audience in Detroit. “The Cuban Revolution — that’s a revolution,” he continued. “They overturned the system. Revolution is in Asia, revolution is in Africa, and the white man is screaming because he sees revolution in Latin America. How do you think he’ll react to you when you learn what a real revolution is?”

By 1962 it was becoming more and more noticeable that Malcolm was straining against the narrow perspectives of the Nation of Islam, a bourgeois nationalist organization with a leadership bent on finding a separate economic niche for itself within the U.S. capitalist system. …

During the last year of his life, Malcolm X spoke out more and more directly about the capitalist roots of racism, of exploitation, and of imperialist oppression. Malcolm never gave an inch to U.S. patriotism, let alone imperialist nationalism. Blacks in the United States are “the victims of Americanism,” he said in his May 1964 talk at the University of Ghana. …

In 1964 Malcolm refused to endorse or campaign for Democratic presidential candidate Lyndon Baines Johnson against Republican Barry Goldwater. “The Democratic Party is responsible for the racism that exists in this country, along with the Republican Party,” he said in the Young Socialist interview. “The leading racists in this country are Democrats. Goldwater isn’t the leading racist — he’s a racist but not the leading racist. … If you check, whenever any kind of legislation is suggested to mitigate the injustices that Negroes suffer in this country, you will find that the people who line up against it are members of Lyndon B. Johnson’s party.” It was also the Johnson administration, Malcolm often pointed out, that was presiding over the U.S. war against the people of Vietnam and the slaughter of liberation fighters and villagers in the Congo. The revolutionary integrity underlying this political intransigence in the 1964 elections set Malcolm apart from, and helped earn him the enmity of, just about every other leader of prominent Black rights organizations or the trade unions, as well as the vast majority of those who called themselves radicals, Socialists, or Communists.

Malcolm X stretched out his hand to revolutionaries and freedom fighters in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and elsewhere. In December 1964 Malcolm, who had demonstratively welcomed Fidel Castro to Harlem four years earlier, invited Cuban revolutionary leader Ernesto Che Guevara to speak before an OAAU meeting in Harlem. At the last minute Guevara was unable to attend but sent “the warm salutations of the Cuban people” to the meeting in a message that Malcolm insisted on reading himself from the platform. …

In the United States, Malcolm X spoke on three occasions — in April and May 1964, and again in January 1965 — to large meetings of the Militant Labor Forum in New York City organized by supporters of the revolutionary socialist newsweekly, The Militant. This was a departure for Malcolm. Even while still a spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, he had spoken on campuses to audiences that were not predominantly Afro-American. Malcolm’s decision to accept the invitation to speak at the Militant Labor Forum, however, was the first time he had agreed to appear on the platform of a meeting outside Harlem or the Black community in any city. …

“One of the first things I think young people … should learn how to do is see for yourself and listen for yourself and think for yourself,” Malcolm told the McComb students at the opening of 1965. “Then you can come to an intelligent decision for yourself.”

This book shows how hard Malcolm X worked to do just that — to help young people step outside the bourgeois influences that surround them and come to decisions for themselves. What’s more, it demonstrates how important an element working with young people was in Malcolm’s own decision to commit his life to building an internationalist revolutionary movement in the United States, one that could join in the fight worldwide to wipe racism, exploitation, and oppression off the face of the earth.