Revolutionary Continuity: The Early Years 1848-1917 by Farrell Dobbs is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for April. This is the first of two volumes covering class struggles and political battles behind the development of a Marxist leadership in the U.S. As a young leader of the Minneapolis Teamsters in the 1930s, Dobbs joined what became the Socialist Workers Party. He was SWP national secretary from 1953 to 1972 and the party’s presidential candidate four times.

This volume covers the founding of the international communist movement by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels in 1848 and its expansion in the U.S. Dobbs wrote that the international “championed the war to defeat the Confederacy in the United States, projecting the need to transform it into a revolutionary war to emancipate the slaves and crush the slaveholding system and planter class.” The excerpt below is from Chapter 2, “Indigenous Origins.” Copyright © 1980 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

In 1852 Joseph Weydemeyer organized the Proletarian League, based on German-American socialists in New York, and began the systematic distribution of Marx’s writings in German. Under his leadership the league sought to deepen labor’s grasp of class politics. Struggles conducted by the trade unions over immediate issues on the job, these Marxists explained, should be accompanied by independent political action. Generalized demands reflecting the needs of the entire working class could in that way be incorporated into a broad program, and the many local struggles could be raised to a higher plane in the form of political confrontations between the workers and the capitalists nationally. In taking this course labor would of necessity back all victims of capitalist exploitation and oppression, seeking to win them as political allies. But the movement could not be allowed to fall into the hands of petty-bourgeois peddlers of social nostrums. Leadership of anticapitalist political action had at all times to be assumed by the workers and for that purpose they, as a class, had to build their own mass party. …

After a time Weydemeyer moved to the Chicago-Milwaukee area, where he again took up political work. Friedrich Sorge, another German immigrant, assumed leadership of the eastern socialist movement. In 1857 Sorge reorganized the former cadres of the Proletarian League as the Communist Club of New York.

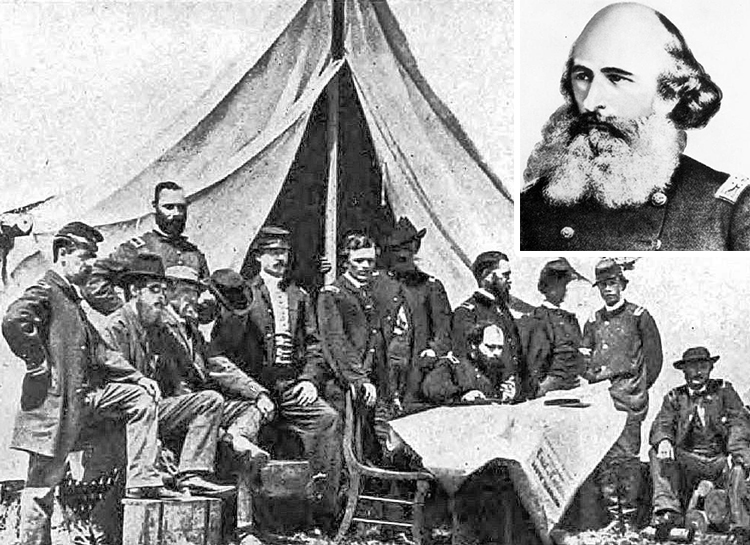

The new group continued socialist propaganda in the labor movement along the lines initiated earlier by Weydemeyer. But anticipating the coming showdown, its activities — like those of other Marxists scattered around the country — began to focus more and more on the abolitionist fight against enslavement of Blacks. Then, in 1861, the antagonisms between the capitalist and planter classes erupted into civil war. Recognizing the progressive character of the bourgeois “free-labor” struggle against the slave system, followers of Marx responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s call to arms. Thereafter the socialists centered their activity on participating as Union Army soldiers in the military side of the war, which caused their work in the labor movement to dwindle for an extended period.

Crushing the slavocracy in 1865 brought the capitalist class definitive control over the nation. A general recasting of governmental policies and social institutions followed, so as to bring them into full conformity with bourgeois needs. That cleared the way for qualitative leaps in machine production, railroad construction, etc., already accelerated by the Civil War. Huge concentrations of capital were amassed to finance large-scale enterprises. Big corporations came into existence. Giant trusts were formed by industrial and banking combines in moves to establish monopolies. This trend soon produced a bumper crop of multimillionaires who fattened on harsh exploitation of wage-labor and wanton depredation of national resources. These plutocrats became the real power behind the bourgeois-democratic governmental facade, and they dealt brutally with all who resisted their ruthless methods of coining superprofits.

Expansion of the factory system also led to transformation of the working class. Unskilled laborers serving as appendages of machines became an increasingly larger section of the class and the weight of the skilled workers declined proportionately. As these contrasting trends revealed, wage-labor was becoming substantially proletarianized. This signified that — in terms of objective developments — the country was entering a new phase. Capitalism, which had just triumphed over the planter aristocracy and which was making fewer and fewer compromises with the independent producers, was already beginning to create “its own gravediggers.”

This period also saw the definitive end to a progressive role for any wing of the bourgeoisie or its political parties.

By 1877, radical reconstruction had gone down to bloody defeat, and not only Afro-Americans but the entire working class had suffered the worst setback in its history. The defeat was engineered by the dominant sectors of the industrial ruling class, who were incapable of carrying through a radical land reform in the old Confederacy and rightly feared the rise of a united working class in which Black and white artisans and industrial workers would come together as a powerful oppositional force, allied with free working farmers.

The rural poor and working class were forcibly divided along color lines. The value of labor power was driven down and class solidarity crippled. Jim Crow, the system of extensive segregation, was legalized. Racism was spread at an accelerated pace throughout the entire United States. The ideological basis for imperialist expansion was laid. All the conditions were created for the forging of the new Afro-American oppressed nationality.