SETH GALINSKY

AND MARY-ALICE WATERS

NEW YORK — After more than two years of debate involving millions of Cubans, a nationwide referendum will be held Sept. 25 to vote “yes” or “no” on a new Families Code. If approved, it would replace the Family Code adopted nearly 50 years ago in a similar referendum, which registered the enormous advances in the social and economic status of women conquered in the first decade and a half of Cuba’s socialist revolution.

The proposal seeks to codify further economic and social gains of women and register changes in social attitudes since the 1975 document was adopted.

It also addresses some of the economic difficulties affecting families in Cuba today, especially regarding responsibility for care of the elderly and children. It deals with a range of contentious social issues, from the rights and responsibilities of parents versus the rights of minor children, to common-law relationships and same-sex marriage.

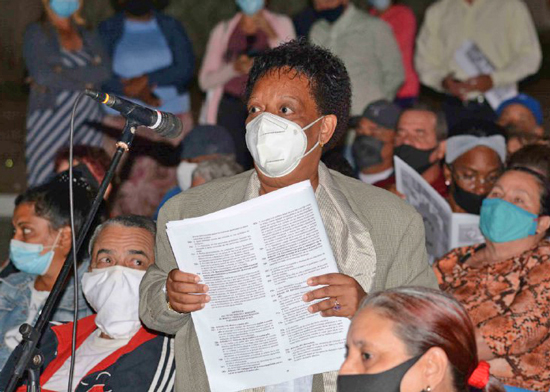

Over a three-month period ending April 30, some 78,000 meetings to discuss the code were held across the island — in every neighborhood as well as in workplaces and rural areas. The draft, originally prepared by a commission established by Cuba’s Council of State, has been revised many times through these and other debates, culminating in a National Assembly session that approved the text to be voted on in September, which is version 25.

While they were in New York City in March for a meeting of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, Militant reporters had the opportunity to talk about the draft Families Code and related economic and social questions with Teresa Amarelle, general secretary of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), and Osmayda Hernández, the FMC’s international relations director. Amarelle is also a deputy in Cuba’s National Assembly of People’s Power and a member of the Council of State.

At the time, the neighborhood meetings were in full swing. Amarelle and Hernández, like FMC members around the country, actively participated in these discussions from the start.

Registration of gains for women

Amarelle noted that the original 1975 Family Code had registered the enormous gains women made during the first years of the revolution. It replaced the prerevolutionary laws on marriage, divorce and alimony that codified the property relations of Cuba’s former capitalist ruling class.

The proportion of women in the labor force has continued to increase, from 24% in 1974 to 55% in 2020. That, together with their rising educational level and involvement in all aspects of Cuban society, has further changed broad social attitudes regarding women.

The new proposed code registers some of those changes. For example, it prohibits domestic violence against women. The 1975 Family Code did not broach the issue, and it was not uncommon at that time for some to deny the existence of the problem. Over the decades, however, the FMC, a mass organization with 4 million members, has played an important role in pushing back the acceptance of domestic violence as “normal” and in protecting women who face it.

Another change is in the legal age for marriage. Under current law it’s 18, but girls can marry at 14 and boys at 16 with their parents’ consent. “It was discriminatory — one age for females and another for males,” Amarelle said.

It also contributed to teenage women dropping out of school and giving up job opportunities after they became pregnant and faced pressure to get married. Helping reduce the high levels of teen pregnancies is one of the FMC’s priorities, working through its neighborhood Counseling Centers for Women and Families (Casas de Orientación), which are in every municipality.

“After some discussion we decided the code should establish a minimum age of 18 without exceptions. That proposal is widely supported,” Amarelle noted.

Care of children and elderly

Articles in the Cuban press describe the “Families Code” as recognizing “many types of families,” and the draft states that what defines a family is a relationship based on “love, affection, solidarity and responsibility.” That’s the future the code strives to bring closer, but it’s far from the reality in a world where commodity relations rule.

As Frederick Engels, co-founder with Karl Marx of the modern communist workers movement, explained with such clarity, what has determined the character of the family at all stages of class society is not love but private property. “True equality between men and women,” he noted, “can become a reality only when the exploitation of both by capital has been abolished and private work in the home has been transformed into a public industry.” That is as true in Cuba as elsewhere.

Much of the new code, in fact, deals with questions of property. The draft document, Amarelle explained, takes up inheritance questions and establishes options for the disposition of property within a marriage and the division of property — such as housing — in a divorce. Cuba has the highest divorce rate in Latin America, a registration, among other factors, of the economic advances and status of women that the revolution made possible.

Among the biggest, and most debated, questions taken up in the Families Code is responsibility for the care of children and elderly relatives. Cuba, with an average life expectancy of 79, has an aging population — more than 20% are 60 years or older. Given the longstanding housing crisis, it’s common for a household to include parents, children and grandparents living together in cramped quarters.

The draft Families Code establishes that elderly family members, those with special needs and minor children have “the right to be cared for,” Amarelle said. Parents and other close family members will have a legal obligation to assure them food and other necessities.

Women are the caregivers in the overwhelming majority of families, and often have to leave their jobs to shoulder that responsibility. They are already entitled to a full year’s maternity leave — 18 weeks at full pay and the rest at 60% — and can also share the leave time with their male partner or another designated family member.

Under the proposed code, they will be able to seek monetary compensation from other family members as part of sharing responsibility for the welfare of elderly relatives.

Debate on same-sex marriage

The new Families Code affirms “the right of all persons to form a family, to marry or establish a civil union, and to adopt.”

“It respects those rights for all,” said Amarelle, from married couples irrespective of sex, to single parents, children being raised by grandparents or other relatives and common-law relationships.

The new measure will ease the process of adoption, including for same-sex couples, and allow for surrogate motherhood, as long as no payment is involved. In Cuba it will be illegal for someone to rent a woman’s body to bear a child. A womb is not a commodity.

“Cuban society today is more inclusive. There are fewer prejudices and more respect for individual rights,” Amarelle said.

The proposed code would give “de facto unions” of two or more years’ duration a legal standing equal to marriage, including for property and inheritance rights. In addition, marriage and common-law unions by same-sex couples would have the same legal status as for heterosexual couples.

The international capitalist press has focused almost exclusively on the same-sex marriage provision, but it’s only one of 474 sections of the Families Code, many of which have been the subject of intense debate. Nonetheless, the proposals to allow same-sex couples to marry and to adopt children have been controversial.

The international capitalist press has focused almost exclusively on the same-sex marriage provision, but it’s only one of 474 sections of the Families Code, many of which have been the subject of intense debate. Nonetheless, the proposals to allow same-sex couples to marry and to adopt children have been controversial.

The proposal to define a marriage as a relationship “between two persons” instead of between a man and a woman was initially debated as part of the new Cuban constitution approved in 2019 by popular referendum. Because of the heated debate it generated, however, all mention of marriage was removed from the final text of the constitution. The proposal was incorporated into the draft Families Code, allowing for further discussion.

According to the Cuban press, some 76% of voting-age Cubans — 6.5 million people — took part in the neighborhood meetings on the Families Code. Of these, 62% voiced support for the draft, indicating it remains more controversial than the new constitution, which was adopted by an 87% majority.

The Conference of Catholic Bishops of Cuba, in a statement issued in February, said the Families Code has “positive elements such as the strengthening of care for older adults or people with different abilities” and measures to protect women and children from domestic violence. But the bishops voiced opposition to the legalization of same-sex marriage. They also criticized the code as “permeated with what is known as ‘gender ideology’ … an attempt to forcibly impose a construct of ideas onto reality” that would lead to “indoctrinating children in school without consent of the parents.”

During the National Assembly debate on the code in July, deputy María Armenia Yi Reina, a Quaker leader in Holguín, stated, “Although it takes up positions I don’t share, based on my Christian principles and faith, I say yes to the draft and urge its submission to a popular vote,” reported the news website CubaDebate.

Another controversial topic is the proposal to change legal norms on parental rights from patria potestad (parental authority or custody) — a widespread legal concept in Latin America and Europe — to “parental responsibility.” This means, the code states, that parents should be “respectful of the dignity and physical and mental integrity of children and teenagers.” A clause on “gradual autonomy” states that parents and courts should grant minor children increasing say over their lives as they mature.

As Amarelle noted in our discussion, the Families Code will have legal consequences, but social relations cannot be changed by decree. “The laws are there, but we have to do the work of convincing and educating,” she said.

Tightened U.S. sanctions hit women

Elaboration of the new family code, the FMC leaders stressed, takes place at the same time the Cuban people are confronting the combined effects of the world capitalist economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and a brutal, six-decade-long economic war by the U.S. government. Washington’s bipartisan policy is designed to deprive them of the economic resources to develop and thus “prove” that a socialist revolution only leads to poverty, desperation and ruin.

U.S. sanctions block the import of medical supplies, fuel, spare parts and other essential products; sharply curtail Cuba’s access to the international banking system; and penalize foreign companies that trade with Cuba. The Trump administration imposed 243 measures further tightening the sanctions, which the Biden White House has overwhelmingly maintained.

A disastrous gas explosion that ripped through the five-star Hotel Saratoga in the heart of Havana last May, costing 47 lives, and the even more devastating fire in August in Matanzas that destroyed a significant portion of Cuba’s oil reserves and left 16 people dead, are only two of the most graphic examples of the consequences of depriving the Cuban people of the equipment and technology needed to maintain the infrastructure of a 21st century economy and protect lives.

“Cuban women have been especially hard hit by the U.S. blockade, which has caused shortages of food, medicine and other necessities,” Amarelle noted. “It’s mostly women who wait in line for scarce products. Although we’ve made some progress over the years in men sharing domestic chores, it’s women who do most of the work at home, taking care of children and elderly grandparents.”

Measures to protect women, workers

From the very first days of the COVID pandemic in 2020, Cuba’s revolutionary government took measures to protect women and other workers. “When schools closed and many women had to stay home with their children, they received 100% of their wages the first month and 60% after that,” Amarelle said.

The FMC and other mass organizations collaborated with the government to shift idled workers to other jobs. That included many of those working in tourism, which was paralyzed during the pandemic. Some were employed as support staff at hotels and schools converted into quarantine centers for COVID patients.

“We also organized messenger services to deliver food and medicine and provide social contact for older adults and others who were isolated at home during the pandemic,” said Osmayda Hernández. “Many were volunteers. But for women and families facing a particularly tough economic situation, we proposed to the Labor Ministry that the women be paid, and that was done.”

In May 2021 the Cuban government launched a mass inoculation campaign, using the highly effective vaccines developed by Cuba’s widely acclaimed biotechnology industry. By early 2022, some 90% of the island’s population was vaccinated. Schools reopened, workers started returning to their workplaces, and foreign tourism slowly began to recover.

Amarelle described a program the Cuban government has instituted to build or renovate housing — at no cost to the family — for women who have three or more children and face economic hardships. The priority given this program is also part of eventually reversing the sustained decline in Cuba’s birth rate.

The FMC also helped launch a neighborhood laundry program called Espumás — a play on the Spanish word for “suds” — that provides jobs for women who cannot work outside the home, usually because they care for children or bed-ridden adults.

“They rent one or two washing machines from the domestic trade ministry, which also supplies the detergent and softener,” Amarelle said. It’s a source of jobs and income for the women and meets a real social need.

There is a big demand for child care centers, the FMC leaders said. Cuba has some 1,086 public círculos infantiles (children’s circles) across the island, with nearly 142,000 kids enrolled, but there are still 56,000 families on a waiting list.

The government has also offered tax breaks for trained child care workers, supervised by the education and public health ministries, to offer private services in their own homes. They charge more than public day care but help bridge the gap for families that can afford it.

In addition, the FMC, together with the Central Organization of Cuban Workers (CTC), the trade union federation, are promoting child care centers called casitas infantiles (children’s centers) set up in workplaces — from factories to farm cooperatives — in consultation with the parents, with resources provided by the entities. As of June there were 41 workplace casitas in Cuba, with another 44 under development.

With the growing number of elderly, Hernández noted, one resource for families is the adult day care centers — the casas de abuelos (grandparents’ centers) — although the demand remains much greater than what’s available.

“A family member drops off an older adult at the center early in the morning and picks them up in the afternoon.”

“The abuelos get breakfast, lunch and a snack there,” Amarelle said. “They take part in exercise programs and cultural activities, learn handicrafts, celebrate collective birthday parties, sometimes even weddings!” The centers also have medical staff.

In face of the ongoing challenges, Amarelle concluded, it’s clear the U.S. economic and political war, which is directed at making life difficult for ordinary Cubans in the hopes they will turn on their own government, is not going to end anytime soon.

“We’ve had to learn to live with the U.S. blockade. We’ve done it for decades and we’ve still been able to develop,” the FMC leader said.

That’s precisely what the U.S. capitalist rulers cannot forgive — that the workers and farmers of Cuba took the factories, utilities and plantations out of the hands of U.S. and Cuban capitalist families, established a state and government that would defend the interests of working people, and set an example for millions around the world.

Telling the truth about that example — including the advances in the fight for women’s emancipation that the revolution made possible — is the most effective way to win support among working people in the U.S. and worldwide for the campaign to demand Washington end its economic, financial and trade sanctions against Cuba.