Cuban revolutionary leader José Ramón Fernández died Jan. 6 at the age of 95. Mary-Alice Waters, a central leader of the Socialist Workers Party and president of Pathfinder Press, collaborated with Fernández on three Pathfinder books.

In the presence of José Ramón Fernández, you quickly sensed you were with a human being of exceptional integrity. His posture alone communicated that fact.

He held himself to the highest standards of revolutionary selflessness, human solidarity and proletarian discipline. Even more important, he knew the men and women he led were capable of acting with the same selflessness and discipline, and he drew the best from them.

His strength was not only his moral clarity. It lay in the consistency of his conduct, a trajectory followed throughout his life as a revolutionary soldier and then as a leader of the Communist Party of Cuba.

Several of us in the leadership of the Socialist Workers Party in the U.S. had the privilege of working with José Ramón Fernández for some two decades in the process of preparing three books. He was one of the four contributors to the small jewel of a book, Making History: Interviews with Four Generals of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces.

He was the principal author of Playa Girón/Bay of Pigs, 1961: Washington’s First Military Defeat in the Americas, a book that contains his testimony in 1999 before the Provincial People’s Court of the City of Havana (an excerpt from the book was run in last week’s Militant).

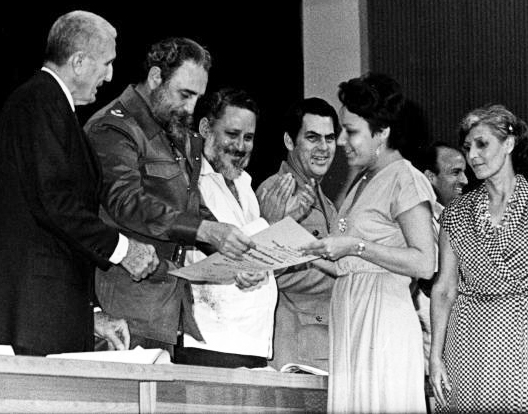

And Fernández’s collaboration in the work that produced Women in Cuba: The Making of a Revolution Within the Revolution by Vilma Espín, Asela de los Santos, and Yolanda Ferrer — and his unflagging enthusiasm and encouragement — was equally indispensable.

All three are published by Pathfinder Press in Spanish and English, and two are published in Farsi. They’ve been distributed around the world and featured at book fairs and political events from the Philippines to Iran, Australia to Sweden, the Dominican Republic to Iraq and beyond.

What left the most profound impression on us in working with Fernández was the attentiveness, courtesy and respect he extended to all around him, including and especially those who to the bourgeois world are the “invisibles” — the men and women who worked with him as drivers, translators, secretaries, cooks, housekeepers, security and more. The dignity, pride, loyalty — and discipline — he inspired in return was always in evidence.

A bourgeois army, or one cast in its mold, imposes its command through “established norms based exclusively on hierarchy and rank,” Fernández told us more than 20 years ago during the interview that appears in Making History. By total contrast, in our army, a socialist army, he said, “discipline is achieved through conscious methods, and the commanding officers derive their authority from the consent of their subordinates; they earn that authority every day by their ability, work and example.”

The army requires very strict discipline, he insisted, “There can be no concessions on that. But it must be very just, very humane, and it must be carried out with the highest moral standards.”

Fernández contrasted the norms of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces to the attitudes that exist among instructors in the U.S. Marine Corps, which he called “bestial” and “contemptible.” He said he was not talking only about the young recruits “who have drowned in the swamps [in ‘training’]. I’m talking about the dehumanizing and denigrating methods of treating young people. That’s unacceptable. It exemplifies the difference between the two types of armies.”

His comments were doubly striking because only a few days earlier, Division Gen. Enrique Carreras, the father of revolutionary Cuba’s air force and one of the other generals who contributed to Making History, had made a similar point. Carreras was talking with us about the differences he knew from his own experience between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Cuba and the Soviet army. “If you’ll pardon my saying so,” he commented, “armies have their own traditions. The Soviets have theirs, of course, very strong ones. We have our own traditions — very appealing ones, which we fight to maintain and guard.”

“For one thing, we are incapable of laying a hand on a soldier. That is the greatest abomination we can imagine,” he said. “Yet once, right in front of several of us, I witnessed a Soviet general strike a soldier for being drunk. I can put up with a lot, but seeing that made me so angry I had to get out of there. Laying a hand on a soldier shows a lack of respect, and that’s something we do not allow. That’s just the way we are.”

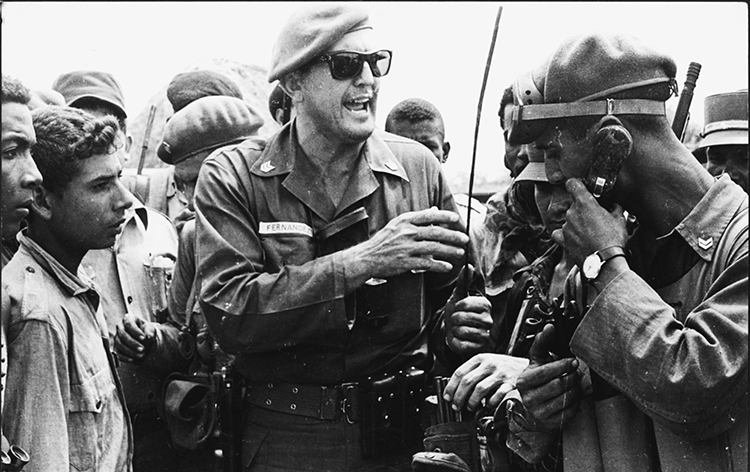

A combat leader

To those of us who knew him, Fernández reminded us above all of the combat leaders of the U.S. working class — men like Farrell Dobbs and Vincent Raymond Dunne — who during the tumultuous years of the early 1960s recruited many of our generation to the Socialist Workers Party and taught us what combat by a politically conscious proletarian vanguard could achieve.

Those were the years during which we learned from the men and women of Cuba what a socialist revolution could accomplish; how working people fighting to transform their world transformed themselves. In the process, they helped begin the transformation of some of us as well. We learned from their example and, first and foremost, wanted to emulate them. Joining those in the United States who were building a proletarian party capable of making such a revolution, we set out on that lifetime course.

It was during those years we also learned firsthand the fighting capacities of the oppressed and exploited toilers of the U.S. Their powerful, unstoppable movement for Black rights brought down the entire institutionalized system of Jim Crow racism that had for nearly a century imposed the terror of its reign throughout the post-Civil War South. That social revolution at the same time began the transformation of race relations in the North and changed the U.S. forever.

A legendary figure

Fernández was already a legendary figure among vanguard fighters in Cuba at the time of the triumph of the revolution in January 1959. A junior officer of the armed forces, he initiated a conspiracy to overthrow the Batista dictatorship, leading a group of military men who became known as los puros — the pure ones. Arrested and convicted for his activities, he had been incarcerated on Cuba’s Isle of Pines, today the Isle of Youth, where many cadres of the July 26 Movement and other revolutionary fighters were imprisoned. Among them was Armando Hart who had led the urban underground before his capture.

Collaborating closely with Hart, Fernández organized and gave military training to the political prisoners who were held in what was called the “Model Prison” — because its design had been copied from a recently built state prison in Joliet, Illinois, then considered the most “secure” penal institution in the world.

As Batista and his top henchmen fled Cuba in the wee hours of Jan. 1, 1959, a massive popular insurrection swept the country in response to the Rebel Army’s call for a general strike. Fernández, along with other imprisoned military officers, was released. It was part of a maneuver by the desperate Cuban bourgeoisie to put together a government and military command that could block the revolutionary forces from taking power.

While others headed straight out of the prison for a military plane sent to carry them back to Havana, Fernández struck out for the military garrison on the Isle of Pines itself. He convinced the troops stationed there to surrender their weapons and, accompanied by an armed escort, returned to the prison. With a machine gun aimed on the gates, he ordered the release of all the incarcerated revolutionaries. After a brief showdown the warden complied, and the battalion Fernández had trained formed ranks and marched out of confinement.

With Hart in civilian control and Fernández in charge of the military, they established on the Isle of Pines one of the first revolutionary governments of Cuba, one that was utterly opposed to the maneuvering bourgeois forces in Havana and utterly loyal to Fidel’s revolutionary movement and its Rebel Army.

Transforming the Rebel Army

José Ramón Fernández will always be remembered as the field commander of the main column of militia forces — trained and led by him — that fought under Fidel’s leadership to defeat the 1,500 mercenaries that invaded Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961. The counterrevolutionary invaders, organized and financed by Washington, were routed in less than 72 hours, and the name Playa Girón became known to history as the first military defeat of U.S. imperialism in the Americas.

But Fernández himself did not consider that his most important or enduring contribution to the revolution.

Having been a junior officer in the Cuban army, who had also received training at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, Fernández told us, “When the revolution triumphed, I joined the Rebel Army as a first lieutenant, the same rank I held previously. Since I was a trained professional (and I say this with no vanity), I was given the task of helping to train the Rebel Army — more than to train it actually, to help transform the Rebel Army and the Revolutionary Armed Forces.”

In the revolution’s early days, he said, “There was not, in general, a clear and firm consciousness of the need for structures, for discipline, for the norms indispensable to a modern-day military force. The members of the Rebel Army — although excellent combatants who had been capable of defeating the corrupt army of the Batista tyranny — needed training along these lines. It was essential to organize and train these cadres in the handling of weapons, in tactics, in combat engineering, in communications, and in all those specific areas of knowledge essential for any armed force.”

Raúl, as minister of the armed forces, “was decisive” in this process, he added.

“Participating in a modest way in building the Rebel Army in the early years, as I did, coming to be vice minister of the armed forces with Raúl under the leadership of Fidel, has been the true fulfillment of my life, this is what has given it meaning. The fact that I was able to participate in the armed struggle in defense of the country at Girón has contributed greatly to this personal fulfillment.”

The significance of the transformation of the Rebel Army and revolutionary militias of 1959 into what became the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Cuba was nowhere confirmed more decisively than some 30 years later in southern Angola in what has become known as the battle of Cuito Cuanavale. That’s when the invading forces of the apartheid South African Defense Force, then the strongest army on the continent, were dealt a crushing defeat by Cuban, Angolan and Namibian forces under the command of internationalist combatants from Cuba.

The spirit of victory

With characteristic insistence, Fernández was always the first to point to the Cuban toilers as the force that won the victory of Playa Girón. “The mercenaries came well organized, well armed, and well supported,” he testified before the People’s Court in Havana in 1999.

“What they lacked was a just cause to defend. That is why they did not fight with the same passion, courage, conviction, valor, firmness, bravery, and spirit of victory as did the revolutionary forces. … The outcome can be explained only by the courage of a people who saw the Jan. 1 triumph as the genuine opportunity to determine their own future.”

That “spirit of victory,” that conviction among the working people of Cuba that with the leadership of Fidel, Raúl, and cadres like Fernández, they were capable of carrying the day militarily against an invading force organized by the strongest imperialist power in the world — that was the example that inspired millions around the world, including here in the United States.

With the truthfulness that marked him, Fernández never failed to point out it was the caliber of Fidel’s leadership that made possible the victory at Playa Girón, and many others.

“History will one day record that few statesmen in the modern epoch of humanity have had the talent, wisdom, courage, and capacity to take advantage of the opportunities of the moment that Fidel has exhibited in defending the revolution,” he told us.

“For almost 40 years [now more than 60] we have been navigating along the edge of a possible attack, firmly defending our sovereignty, the revolution, and socialism.” We have “proved capable of defending our principles while avoiding war.”

Defending principles while avoiding war — that is the ultimate strategic goal of revolutionary armed forces. Only along that road can there be space for the class struggle to unfold, involving the largest possible numbers of the toilers, and experience through which we can transform ourselves.

Fernández shouldered many other responsibilities in Cuba’s revolutionary leadership, including as minister of education for some 20 years, vice president of the Council of Ministers for 30, and president of the Cuban Olympic Committee.

The impact on others of the ongoing march of the revolution to which he gave his loyalty and every fiber of his being will continue. And the importance of that ongoing march will be registered not only in Cuba but far beyond.

Making the example of the Cuban Revolution — and of the men and women like Fernández who made it — known to working people in the United States and around the world is above all our responsibility. That example is needed by the millions looked upon by the rulers as “deplorable” or worse, whose revolutionary capacities will one day prove no less powerful than those the Cuban toilers have already demonstrated for more than 60 years.