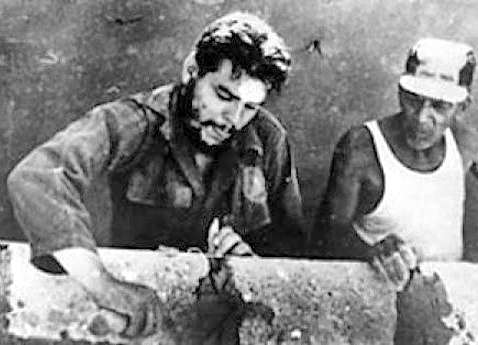

The excerpt below is from Socialism and Man in Cuba by Ernesto Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. The French edition is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for April. The piece is from “Che’s Ideas Are Absolutely Relevant Today,” an Oct. 8, 1987, speech by Castro commemorating the 20th anniversary of Guevara’s death. In 1959 the Cuban Revolution opened the socialist revolution in the Americas, initiating a renewal of Marxism and inspiring a new generation of revolutionary-minded youth worldwide. In the mid-1980s, Castro led a rectification process in Cuba to reverse the growing impact of bureaucratism and use of capitalist methods on working-class consciousness and morale by re-emphasizing voluntary labor and deepening involvement of workers and farmers in political life. Copyright © 1989 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

What are we rectifying? We’re rectifying all those things — and there are many — that strayed from the revolutionary spirit, from revolutionary work, revolutionary virtue, revolutionary effort, revolutionary responsibility; all those things that strayed from the spirit of solidarity among people. We’re rectifying all the shoddiness and mediocrity that is precisely the negation of Che’s ideas, his revolutionary thought, his style, his spirit, and his example.

I really believe, and I say it with great satisfaction, that if Che were sitting in this chair, he would feel jubilant. He would be happy about what we are doing these days, just like he would have felt very unhappy during that unstable period, that disgraceful period of building socialism in which there began to prevail a series of ideas, of mechanisms, of bad habits, which would have caused Che to feel profound and terrible bitterness. [Applause]

For example, voluntary work, the brainchild of Che and one of the best things he left us during his stay in our country and his part in the revolution, was steadily on the decline. It became a formality almost. It would be done on the occasion of a special date, a Sunday. People would sometimes run around and do things in a disorganized way.

The bureaucrat’s view, the technocrat’s view that voluntary work was neither basic nor essential gained more and more ground. The idea was that voluntary work was kind of silly, a waste of time, that problems had to be solved with overtime, with more and more overtime, and this while the regular workday was not even being used efficiently. We had fallen into the bog of bureaucracy, of overstaffing, of work norms that were out of date, the bog of deceit, of untruth. We’d fallen into a whole host of bad habits that Che would have been really appalled at. …

Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that money was becoming man’s concern, man’s fundamental motivation. He who warned us so much against that would have been appalled. Work shifts were being shortened and millions of hours of overtime reported; the mentality of our workers was being corrupted and men were increasingly being motivated by the pesos on their minds.

Che would have been appalled for he knew that communism could never be attained by wandering down those beaten capitalist paths and that to follow along those paths would mean eventually to forget all ideas of solidarity and even internationalism. To follow those paths would imply never developing a new man and a new society. …

Those paths I repeat — and Che knew it very well — would never lead us to building real socialism, as a first and transitional stage to communism.

But don’t think that Che was naive, an idealist, or someone out of touch with reality. Che understood and took reality into consideration. But Che believed in man. And if we don’t believe in man, if we think that man is an incorrigible little animal, capable of advancing only if you feed him grass or tempt him with a carrot or whip him with a stick — anybody who believes this, anybody convinced of this will never be a revolutionary; anybody who believes this, anybody convinced of this will never be a socialist; anybody who believes this, anybody convinced of this will never be a communist. [Applause]

Our revolution is an example of what faith in man means because our revolution started from scratch, from nothing. We did not have a single weapon, we did not have a penny, even the men who started the struggle were unknown, and yet we confronted all that might, we confronted their hundreds of millions of pesos, we confronted the thousands of soldiers, and the revolution triumphed because we believed in man. Not only was victory made possible, but so was confronting the empire and getting this far, only a short way off from celebrating the twenty-ninth anniversary of the triumph of the revolution. How could we have done all this if we had not had faith in man? …

In essence — in essence! — Che was radically opposed to using and developing capitalist economic laws and categories in building socialism. He advocated something that I have often insisted on: Building socialism and communism is not just a matter of producing and distributing wealth but is also a matter of education and consciousness. He was firmly opposed to using these categories, which have been transferred from capitalism to socialism, as instruments to build the new society.

At a given moment some of Che’s ideas were incorrectly interpreted and, what’s more, incorrectly applied. Certainly no serious attempt was ever made to put them into practice, and there came a time when ideas diametrically opposed to Che’s economic thought began to take over. …

But many of Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today, ideas without which I am convinced communism cannot be built, like the idea that man should not be corrupted; that man should never be alienated; the idea that without consciousness, simply producing wealth, socialism as a superior society could not be built, and communism could never be built. [Applause]