NEW YORK — Albert Woodfox spent nearly 44 years in solitary confinement in a 6-by-9 foot cell in Louisiana’s notorious Angola prison. He and fellow prisoners Herman Wallace and Robert King came into the sights of authorities there after organizing a chapter of the Black Panther Party and joining with fellow prisoners to fight against the brutal conditions they faced.

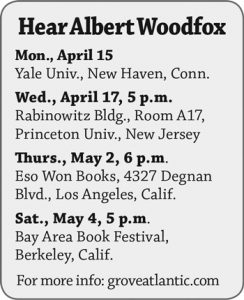

He won his freedom in 2016 and is now on a national speaking tour promoting his just released book Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope. He is campaigning for an end to solitary confinement. (See ad this page.)

He won his freedom in 2016 and is now on a national speaking tour promoting his just released book Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope. He is campaigning for an end to solitary confinement. (See ad this page.)

The tour and book expose the abusive conditions that exist in prisons across the country. And just as importantly, they highlight the example set by Woodfox and others who stand up to those abuses and express solidarity with others who assert their humanity. The tour is organized by his publisher, Grove Atlantic.

At a meeting of over 150 people at the Brooklyn Public Library March 27 he explained how the prison system is designed to “break a man’s spirit.” The authorities in Angola used racial segregation as the most effective way to control the prisoners and to keep inmates divided. To combat that, the three began to organize interracial basketball and football games and to talk to fellow prisoners regardless of skin color, to advance solidarity. “We were making a difference,” he said.

Prison officials saw this as a threat. They framed up Woodfox and Wallace for the 1972 killing of a guard during a riot in the prison. King was victimized in a separate frame-up after a fellow prisoner was stabbed to death on his cellblock. Together they became known as the Angola 3. They never stopped organizing and fighting.

King was released in 2001. Wallace died in October 2013, three days after his release.

To confront their conditions, “we turned toward society, not away,” Woodfox said. “I became a voracious reader. Mao, Malcolm X, Ho Chi Minh, Martin [Luther King Jr.], Gandhi,” among others. He studied law to be better able to fight and help others. “Other prisoners would sneak us law books into our cells.”

Woodfox said there were two battles they undertook while in solitary that he was most proud of. One was a hunger strike to stop the inhumane way meals were shoved under prisoners’ cell doors, as if they were animals. The unity and determination of the strikers forced prison authorities to cut slots in the doors for passing the food trays.

The second was a fight against humiliating strip searches.

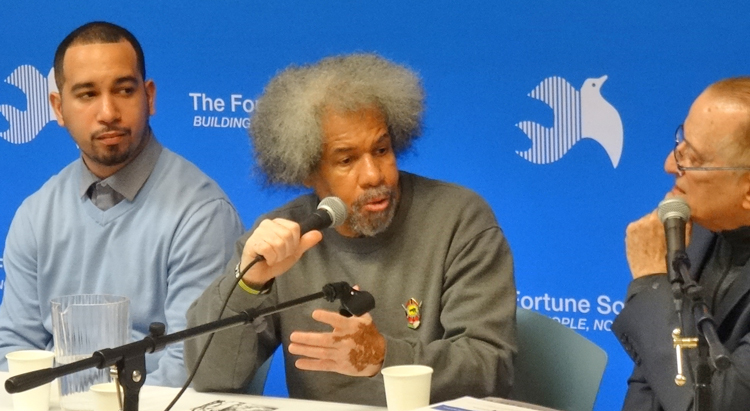

At the meeting in Brooklyn and the next day at the Fortune Society in Long Island City, Woodfox was asked his opinion on a bill before the New York Senate that would limit solitary confinement to 15 consecutive days.

“Try it for one day,” he told those at the Fortune Society, “and see what you think.” He is campaigning for the total elimination of solitary confinement.

Several former prisoners spoke from the floor about their experiences in New York state lockup. “They treat us like animals,” one said to general agreement.

Another, who was recently released after 23 years behind bars, described being “thrown in the box [solitary] because the guards said I wasn’t eating my lunch fast enough.”

Guards believe “they can do whatever they want, beat you, even kill you and nothing will happen to them,” Woodfox said, because they think no one knows or cares. “Until that changes, the abuse will continue. There needs to be oversight and accountability.”

His book and tour are helping spread the word.

Lanie Fleischer and Seth Galinsky contributed to this article.