During a winter when a new epidemic, the coronavirus, is spreading rapidly in China and beyond, when more traditional influenzas have killed some 20,000 people in the U.S. alone, and at a time when Washington is escalating its economic war against the Cuban Revolution, the Pathfinder Press publication of Red Zone: Cuba and the Battle Against Ebola in West Africa is a beacon of light.

The book — a gripping account by Enrique Ubieta Gómez about the Cuban Revolution’s response to the 2014 epidemic of the deadly Ebola virus in West Africa — is a powerful argument for socialist revolution and a close-up look at the human beings such a revolution produces. It’s impossible not to compare the compassion and solidarity of the policies of the Cuban government and the men and women who carry them out and with the devil-take-the-hindmost profit-driven character of medical care in the U.S., where the care you need is a costly commodity. Much of the book is interviews with those Cubans who volunteered to lead the fight against the disease.

Ubieta’s account also thoroughly disproves Washington’s slander that Cuba’s international medical assistance program engages in “exploitative and coercive labor practices” toward its volunteer doctors, as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said last summer, or that Cuban doctors’ chief motivation in taking international assignments is to get their hands on more money.

When the World Health Organization declared the Ebola epidemic in West Africa a “Public Health Emergency” in August 2014 and the United Nations appealed for nations to join the fight to contain and reverse it, several governments responded with economic aid. The U.S. rulers sent 500 soldiers to build hospitals and other facilities.

At that point Cuba was the only government to respond with medical personnel.

12,000 volunteer to go

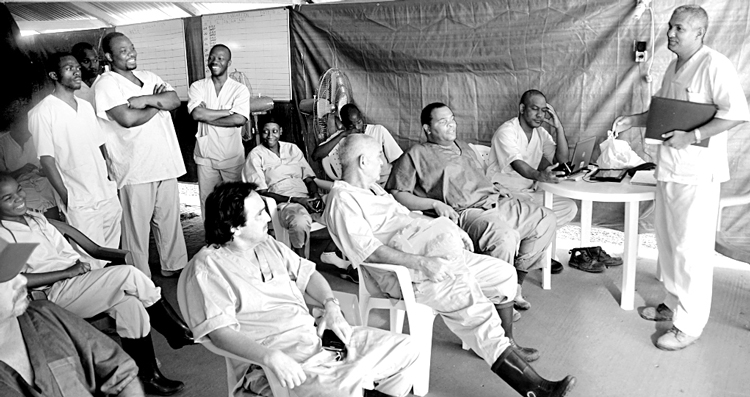

Cuba’s revolutionary leadership acted rapidly, calling for volunteers. Some 12,000 doctors and nurses answered. Of these, 256 were selected and began specialized training. The first contingent left Cuba for Sierra Leone Sept. 19, others followed in the next few weeks.

Dr. Luis Escalona, an officer in Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces, exemplifies the attitude of the medical volunteers. He called the head of the medical services department about the mission, who told him, “We’re looking for people willing to go to Africa and fight Ebola.”

“I replied, ‘Sign me up,’” Escalona recounts.

“He said, ‘You could die in Africa.’

“I repeated, ‘Sign me up.’”

Ubieta quotes what Fidel Castro, the central leader of the Cuban Revolution, said about the volunteers, comparing the Cuban fight against Ebola to the country’s military volunteers who joined Angola’s battle against apartheid South Africa’s invasions decades earlier.

“Just as no one has the slightest doubt that the hundreds of thousands of combatants who went to Angola and other African and Latin American countries gave humanity an example that can never be erased from human history,” Castro wrote, “it cannot be denied that the heroic actions of the army of white coats will occupy one of the highest places of honor in that history.”

The Cubans methods were different

Cuban doctors and nurses told Ubieta how they overcame their fear with humor, comradeship and dedication to their work. How they comforted the dying as they fought for the survival of each and every person. How they treated their patients with respect and dignity. How they learned about and appreciated the distinctive culture of the people they treated.

The deaths of children touched them particularly deeply. “These were hard blows,” Ricardo Zamora Álvarez de la Campa, a nurse, said, “and what always came to mind were our own kids, who were nearly the same ages: four, five years old.”

While the Cuban volunteers were putting enormous effort into saving lives, they also were seeing up close the social and political conditions that allowed the Ebola epidemic to flare up in West Africa. Ubieta places the blame squarely on the capitalist system, whose exploitation holds much of Africa’s people in underdevelopment and poverty.

Dr. Jorge Delgado, head of the Cuban brigade in Sierra Leone, explains, “Ebola is a disease of poverty … just as malaria is a disease of poverty, along with pneumonia, meningitis, and all other infectious diseases associated with malnutrition.” Delgado said that in a few days previous to his interview, 12 or 13 children had been admitted to his clinic. “None tested positive for Ebola. What did they test positive for? Pneumonia, cerebral malaria, gastroenteritis, meningitis, malnutrition with sepsis of various kinds — all associated with poverty.”

“Capitalism engenders poverty, biological warfare, the profit drive, and ecological catastrophes,” Ubieta comments. “In Liberia, the infant mortality rate is 56 per 1,000 live births (in Cuba it’s 4.2). Maternal mortality per 100,000 live births is 990 (44 in Cuba). … Yet Liberia has only 0.1 doctor per 10,000 inhabitants. In Sierra Leone the figures are even starker.”

Red Zone shows the sharp contrast between the approach of the Cuban revolutionaries and that of the imperialist countries. “We can fight for the lives of patients,” Dr. Carlos Castro Baras said. “But an epidemic is defeated on the ground by actions taken with the people, cutting off contacts with those infected, tracking the chain of transmission, raising awareness among them.”

Epidemiologist Osvaldo Miranda Gómez described how they developed relationships with the Ebola patients and won their confidence. “One afternoon there were about five or six patients gathered together. They were happy because they knew they would be discharged the following day,” he said. “We had a cell phone playing music, and we started to joke around and sing, and they started dancing. It was nice, because some of them had come to the treatment center in serious condition.”

Some of the patients became volunteers in the clinic, Dr. Miranda said. “It’s a very rewarding experience, because they’re the ones who help convince new patients.”

Red Zone also points to the future of the Cuban Revolution, which has survived for more than six decades in spite of a bipartisan political and economic war waged against it by 12 consecutive U.S. administrations.

Only two Cuban volunteers died during the mission, both of malaria, and only one, Dr. Félix Báez, contracted Ebola. He was transferred in a coma to Switzerland.

When it wasn’t clear whether Báez would survive, the Cuban press kept the population up to date on his condition and published a brief message from his son, Alejandro, that elicited an explosion of support across the island. As Báez recovered, Alejandro published another letter expressing gratitude for that support and taking on those who had questioned the mission.

“Yes, my father got sick, but that doesn’t mean, as many say, that he shouldn’t have gone. I say it’s just the opposite,” Alejandro wrote. “My father was over there putting his life on the line because he felt it was his duty to help those who needed it the most. But I say: isn’t that what makes us human?”

After his recovery, Báez insisted on returning to his post in Africa.

Cuba’s revolution is an example

Ubieta sees the spirit of Cuban volunteers in Africa and on other internationalist missions as an indicator of the continuing strength of the revolution. “The US blockade continues, and it punishes average Cubans. But whenever there is a call to action, thousands of volunteers step forward,” he said. “The hundreds of doctors and nurses who volunteered and those who went to West Africa are irrefutable proof of a fact: among the people there are moral reserves — reserves that need to be summoned.”

For class-conscious workers in the U.S. and other imperialist countries, reading Red Zone can inspire us to emulate the Cuban Revolution by building a mass working-class movement to take political power and transform ourselves in the process.