Protests against cop brutality and police killings are continuing in cities and small towns across the country, as well as worldwide. They’ve remained strongest and most determined where new cases of police violence have been forced into public view, or where longstanding fights by families whose loved ones have been slain by police have gained new publicity. These fights revolve around demands for the arrest and prosecution of the cops responsible.

“These protests have helped bring a light to our fight,” Jimmy Hill, father of Jimmy Atchison who was shot and killed by cops in Atlanta last year, told the Militant at a June 27 rally of several hundred organized by the NAACP.

“We have been waiting on a grand jury indictment for 1½ years, we’re never going to give up,” Hill said. Atchison was shot dead by now-retired cop Sung Kim in January 2019 as he tried to surrender to cops who were chasing him. He was unarmed.

Elsewhere in Georgia, a Glynn County grand jury finally indicted three white vigilantes June 24 on murder charges in the death of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man who was shot as he jogged in Brunswick Feb. 23. Ex-cop Gregory McMichael, his son Travis McMichael, who fired the shots, and William Bryan Jr., who videotaped the killing and worked with the McMichaels to trap Arbery, were each charged with malice murder, felony murder and aggravated assault.

“The indictment means a big accomplishment,” Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, told CBS46 News. But “it’s not time for celebration yet because we want to get them sentenced properly.”

For more than two months no arrests were made and facts about the case were swept under the rug by local cops and prosecutors. Finally, with the public release of the video and the outcry that ensued, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation arrested the McMichaels May 7 and Bryan May 21.

The June 24 indictment of the vigilantes came after Arbery’s name and countless others became widely known from protests around the country, putting growing pressure on Georgia officials.

Breonna Taylor killing

Other fights continue. More than 500 people rallied on the steps of Kentucky’s Capitol in Frankfort June 25, demanding that the three cops who shot and killed emergency room technician Breonna Taylor in her apartment in Louisville be charged.

“We wanted to keep it peaceful but make some noise and let the government know, enough is enough,” Kayla Schnell, a 24-year-old restaurant server who came on one of several buses from Louisville, told the Militant at the rally. “I invited friends to come with me but I also knew I was going to be here no matter what. This fight has been getting international support.”

Armed with a “no-knock” warrant, cops busted down the door to Taylor’s apartment unannounced late at night March 13. In response to the break-in, Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, fired one shot that hit an officer in the leg. The cops then fired over 20 rounds into the apartment, killing Taylor with eight bullets. Walker was arrested and charged with attempted murder, but as the facts of the raid came out and protests began, charges were dropped.

The officers were placed on administrative leave. Three and a half months later, one of them, Brett Hankison, was fired from the force. But none of the cops have been charged.

Outrage over killing of Lopez

The cover-up of the April 21 cop killing of Carlos Adrian Ingram Lopez in Tucson, Arizona, is also coming apart. For over two months cops refused to turn the officer’s video of Lopez’s death over to his family. Just before it was made public June 24, the three officers involved all resigned.

Some 400 people attended a vigil for Lopez, a cooking school graduate, at the El Tiradito shrine in Tucson June 25 and marched to the city’s police headquarters.

“Two months ago, Tucson Police Department killed our son, our grandson, our nephew, our brother and a father to a 2-year-old girl,” Lopez’s aunt, Diana Chuffe, told the Arizona Daily Star at the protest, speaking for the whole family. “Yesterday, they killed him all over again by smearing him in the media.”

An autopsy report by the Pima County medical examiner’s office had claimed the cause of Lopez’s death was “undetermined.” It said Lopez died of sudden cardiac arrest, with physical restraint by officers and cocaine intoxication “contributing” factors.

In fact, Lopez was killed at his grandmother’s house when cops handcuffed him, put a mesh spit guard over his head and held him face down on the garage floor for 14 minutes, as a cop’s body camera video shows. Lopez kept screaming “Nana ayudame” (grandma help), and pleaded for water more than a dozen times, but the cops wouldn’t let up until he stopped breathing.

Lopez was having a mental health crisis that day, acting erratically and running around the house naked. So his grandmother called 911 to get medical assistance. Instead, the cops showed up.

City officials paint the police department in Tucson as “progressive,” banning cops from using chokeholds and requiring them to participate in “cultural awareness” training. But for the working people there, many of whom are Latino, these reforms haven’t changed a thing.

In Aurora, Colorado, thousands of people took to the streets June 27 to protest the cop killing of 23-year-old Elijah McClain in August 2019. McClain was walking home from a convenience store when three cops stopped him, saying they had a complaint about a young Black man acting “suspicious.” One officer put the 140-pound youth in a chokehold, although he was already handcuffed on the ground. On a now public body camera video, McClain can be heard saying, “I just can’t breathe.”

McClain’s family said he was always very sensitive. He would go to a local shelter and play his violin to help soothe the animals.

Will ‘defund police’ stop brutality?

These public protests fighting particular instances of cop brutality are effective in getting the truth out and in more and more cases forcing authorities to indict the cops. They are educating millions about the real character of the cops under capitalist rule.

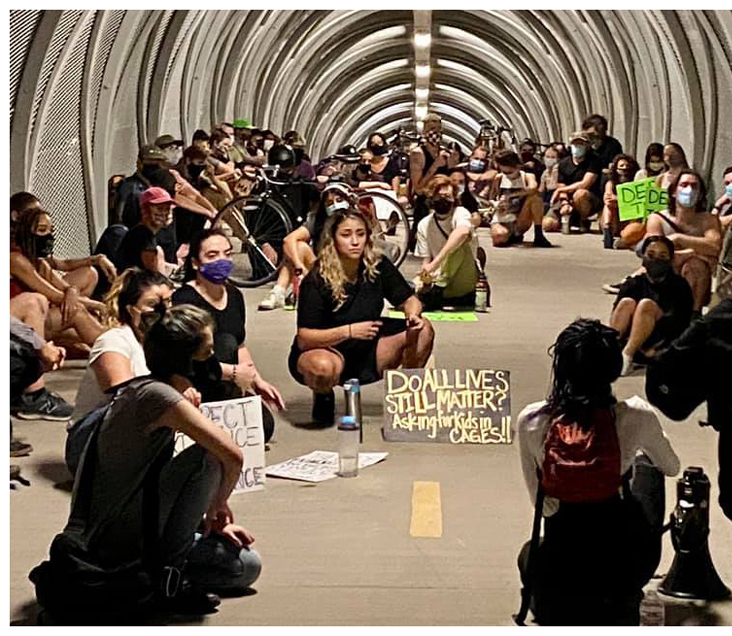

But elsewhere, protests have centered on demands to “defund the police” and other reforms aimed at ameliorating the most brutal aspects of the capitalist “justice” system. This takes working people away from identifying and fighting the root cause of the problem. Prominent at these actions are liberals promoting “lesser-evil” Democratic Party candidate Joe Biden to get rid of President Donald Trump.

There is no way to “improve” the conduct of the cops, whose function under capitalism is to mete out punishment to working people to protect the profits, property and power of the ruling capitalist class. The only road to get rid of police brutality is to put an end to the social system that breeds it, by organizing working people in our millions to take political power into our own hands. Workers and farmers in Cuba demonstrated this is possible when they made a socialist revolution in 1959, a revolution they have continued to defend for over six decades.

Amy Husk in Louisville, Kentucky, and Janice Lynn in Atlanta contributed to this article.