Feb. 21 marks the 56th anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X. Malcolm was “the face and the authentic voice of the forces of the coming American revolution. He spoke the truth to our generation of revolutionists,” Jack Barnes, then national chairman of the Young Socialist Alliance, told a March 1965 memorial meeting in New York City.

The example Malcolm set as a revolutionary leader of the working class is more important than ever to working people of every skin color seeking ways to resist the impact of the capitalist crisis today. His legacy can be read and studied in the eight collections of speeches and interviews published by Pathfinder Press, and in Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power by Barnes, today the national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party.

Malcolm was born in 1925. When he was 6 his father, a follower of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, was murdered by a racist gang. As a teenager, Malcolm became involved in petty crime. He was sent to prison on burglary charges in 1946. It was while behind bars that Malcolm began to read broadly — history, philosophy, science, literature, whatever he could find in the prison library.

His conversion to Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam while in jail was the particular road he took that allowed him to pull his life together and begin acting on his own capacities. Following Malcolm’s release in 1952, he became a prominent spokesman of the Nation, speaking out against all forms of anti-Black racism, as well as U.S. government policy at home and abroad.

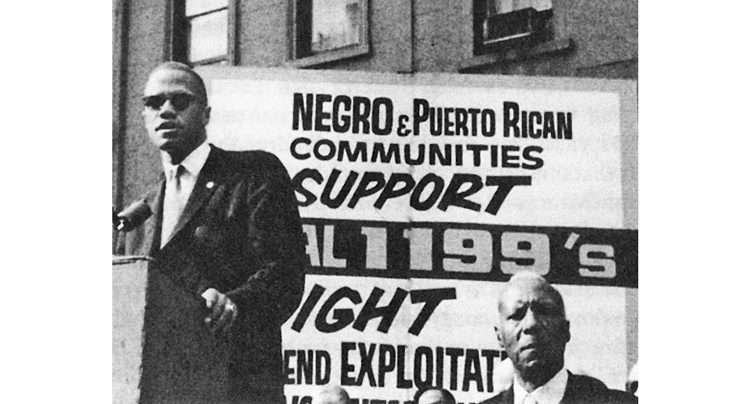

By the early 1960s, Malcolm was increasingly attracted to the rising struggles to end Jim Crow segregation and of oppressed peoples around the world. His initiatives to join these struggles came into growing conflict with the perspectives of the Nation of Islam, a bourgeois nationalist organization that sought to carve out a place for itself within American capitalism. In March 1964, Malcolm split from the Nation.

During the last year of his life, Malcolm organized and spoke with increasing clarity on questions that remain central for working people today.

“I believe that there will ultimately be a clash between the oppressed and those that do the oppressing,” he told a television reporter in 1965. “I believe that there will be a clash between those who want freedom, justice, and equality for everyone and those who want to continue the systems of exploitation. I believe that there will be that kind of clash, but I don’t think that it will be based upon the color of the skin, as Elijah Muhammad had taught it.”

Malcolm acted on his conviction that the fight to end racial oppression here was part of the worldwide struggle against colonialism and imperialism. He met and worked with other revolutionaries, taking two extended trips to Africa and the Middle East. He was attracted to the workers and farmers governments that had come to power through popular revolutions in Algeria and Cuba.

He was drawn to work with the Socialist Workers Party in the U.S.

Speaking at a Militant Labor Forum in New York in May 1964, Malcolm pointed to the example set by the Chinese and Cuban revolutions, where the capitalists and landlords had been expropriated. In contrast, he said, “The system in this country cannot produce freedom for an Afro-American. It is impossible for this system, this economic system, this political system, this social system, this system, period.”

Malcolm remained a determined fighter for the rights of Black Americans, increasingly seeking opportunities to collaborate in action with those fighting to expand voting rights, access to jobs and public facilities, organize unions, and more. But unlike prominent figures in the fight for Black rights, such as Martin Luther King Jr., he did not act on the illusion that U.S. capitalist society, its government and its twin political parties could be won to advancing the interests of the oppressed.

He rejected the trap of choosing the “lesser evil” between the capitalist Democratic and Republican parties. He stood virtually alone in the 1964 presidential election, apart from the SWP, in refusing to campaign for — and subordinate the fight for Black rights to — the election of Democrat Lyndon Johnson.

Malcolm understood, from his own experience, that the biggest challenge for those oppressed and exploited under capitalism is to throw off the self-image that the ruling class teaches us — to gain confidence in our own capacities. In one of the last interviews he gave before he was killed, Malcolm was asked if he was trying to wake people to their exploitation.

“No, to their humanity, to their own worth, and to their heritage,” he replied.

He became convinced by meeting Algerian revolutionaries who were white that Black nationalism was an inadequate political outlook. “I haven’t been using the expression for several months,” Malcolm told Barnes in one of his last interviews.

“Malcolm challenged American capitalism from right inside,” Barnes said, in his 1965 tribute. “He was living proof for our generation of revolutionists that it can and will happen here.”

In the decades since Malcolm’s assassination, numerous books have been written about him, along with movies and plays. Nearly every one distorts or obscures his legacy as a revolutionary leader of the entire working class.

But as Malcolm told young civil rights fighters in 1965, you need to “see for yourself and listen for yourself and think for yourself.”

A good way to start is with Malcolm’s speeches and by reading Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power. These titles are available at the book centers listed in the directory or from pathfinderpress.com.