The junta in Myanmar has been unable to quell daily protest marches, candlelight vigils and strikes opposing the Feb. 1 military coup despite killing hundreds of protesters and jailing thousands.

The police pulled over several public transit buses for no reason April 2 in Yangon’s North Okkalapa Township, a working-class stronghold of opposition to the military regime. “They told the passengers to get off and kneel down. They beat not only the passengers but also the drivers,” a witness told Irrawaddy, a news site that backs the Civil Disobedience Movement.

The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners said April 7 that the death toll stands at 598, most killed when the police and army units fired on unarmed demonstrators.

The junta, led by Gen. Min Aung Hliang, seized power after the National League for Democracy, a capitalist party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, won the November elections in a landslide. Suu Kyi had shared power with the military command since the party first won an overwhelming majority in the 2015 elections. Under the 2008 constitution, the high command automatically controls 25% of the seats in the parliament, and key ministries.

The junta, led by Gen. Min Aung Hliang, seized power after the National League for Democracy, a capitalist party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, won the November elections in a landslide. Suu Kyi had shared power with the military command since the party first won an overwhelming majority in the 2015 elections. Under the 2008 constitution, the high command automatically controls 25% of the seats in the parliament, and key ministries.

As the military unleashes further repression, working people and youth have been adjusting their tactics to keep up pressure on the regime while minimizing their own losses.

In Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city and the one that has suffered the brunt of the repression, smaller groups — including some led by members of the garment workers union — are carrying out short actions that disperse before the police or army units have time to attack.

Early in the morning April 6, protesters sprayed messages in red paint all over Yangon. “The blood has not dried,” read one message. Another appealed to soldiers: “Don’t kill people just for a small salary as low as the cost of dog food.”

The junta has relied on the police and elite army units to repress the peaceful protests and strikes by workers. But the bulk of the soldiers are from rural farm areas, as well as unemployed youth from the cities.

Unequal combat

Daily protests, some in the thousands, and strikes that have involved tens of thousands of workers over the past two months, continue.

Workers, farmers and youth in at least a dozen small towns and villages have stood up to police and military assaults with bows and arrows and hunting rifles.

In Kalay city, in a majority Chin ethnic area in northern Myanmar, young people armed with rifles and homemade weapons fought for hours March 28 with soldiers from an army unit and police who were using machine guns and hand grenades.

Later in the week, seven plainclothes police captured by the protesters were released in exchange for nine residents detained for violating the evening curfew imposed by the junta. Unlike the way the junta treats protesters, “We treated them [the police] well. There were no beatings,” a protester told Myanmar Now.

History of ethnic divisions

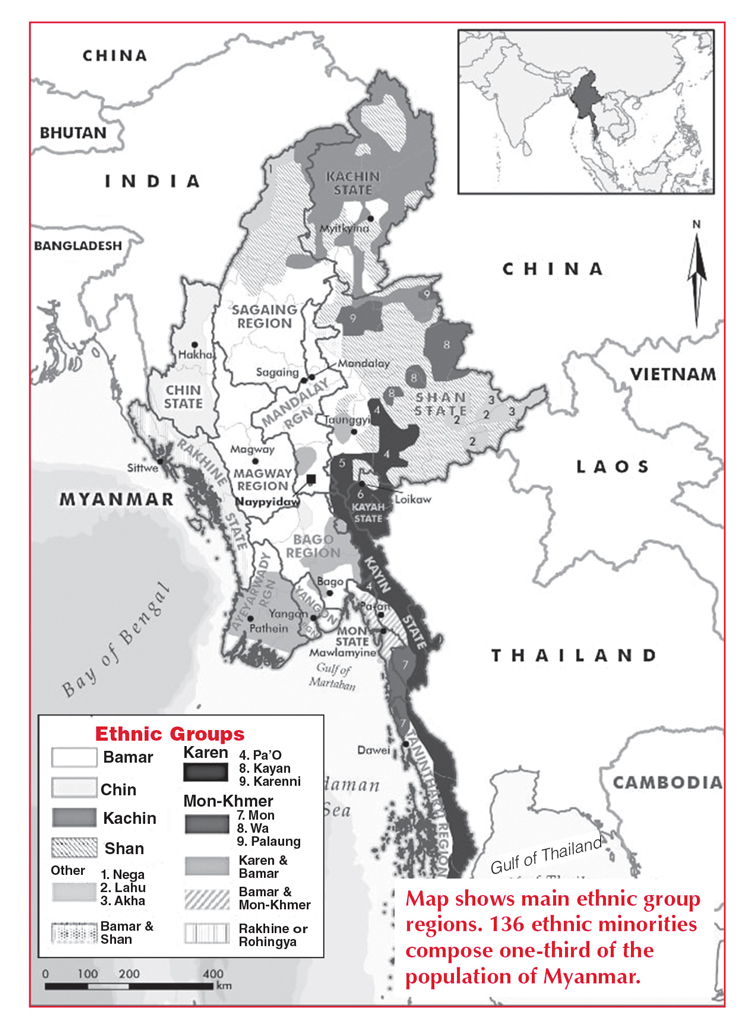

Myanmar’s capitalist rulers have relied on the military to wage a series of wars with dozens of armed groups in mountainous border areas where ethnic minorities make up the majority of the population. By 2013 the government had negotiated de facto, if uneasy, cease-fires with most of them.

These conflicts originate in the divide-and-rule strategy of the British colonial regime. Their continuation is in part because no revolutionary working-class leadership emerged from the hard-fought battles that brought colonial rule to an end. The British rulers had excluded the Bamar majority from the colonial army, instead recruiting from the Karen, Kachin and Chin ethnic minorities. For government positions, it brought in officials from India.

After gaining independence in 1948, the new government reversed the discrimination against the Bamar, but at the expense of the ethnic minorities.

More than a third of the population is made up of 135 ethnic minorities recognized by the government.

The largest of these are the Shan with 9%, Karen 7%, Rakhine 4% and ethnic Chinese with 3%. The government does not recognize Rohingya, a Muslim minority in the west, as an ethnic minority. In 2017 the military carried out deadly assaults on Rohingya, forcing 700,000 to flee to neighboring Bangladesh. Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy defended the repression.

The junta wants to keep the ethnic armies from bolstering the movement against the coup. At the end of March it announced a unilateral cease-fire to run through the end of April.

The United Wa State Army, based on the Wa people — one of the smaller ethnic groups — has not criticized the coup. But it is the largest standing ethnic army, with 25,000 soldiers, and surface-to-air missiles and heavy artillery provided by Beijing. It is not willing to jeopardize its long-standing accommodation with the Myanmar military high command that accepts its control over a large region along the Chinese border.

A dozen other armed groups have expressed their solidarity with the nationwide protests against the military junta.

Both the Kachin Independence Army and the Karen National Union have clashed with the Myanmar military since the coup. The Karen National Union noted in a March 30 statement that despite a 2013 cease-fire agreement, “the Burmese military has been expanding its military presence in several Karen territories” for years.

Some 12,000 Karen people fled their homes in the Papun and Nyaunglebin districts after the junta carried out airstrikes March 27-31, killing 14 villagers.

Demonstrations in solidarity with those fighting military rule in Myanmar took place across the U.S. March 28 and April 3. More actions are planned.

James Khyne in Houston contributed to this article.