NEW YORK — The victory of the Cuban armed forces and volunteer militias against U.S.-trained and -equipped mercenaries at Playa Girón in April 1961 demonstrated “the determination of the Cuban people to defend the socialist revolution, whatever it took,” said Ambassador Pedro Luis Pedroso, Cuba’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, April 18.

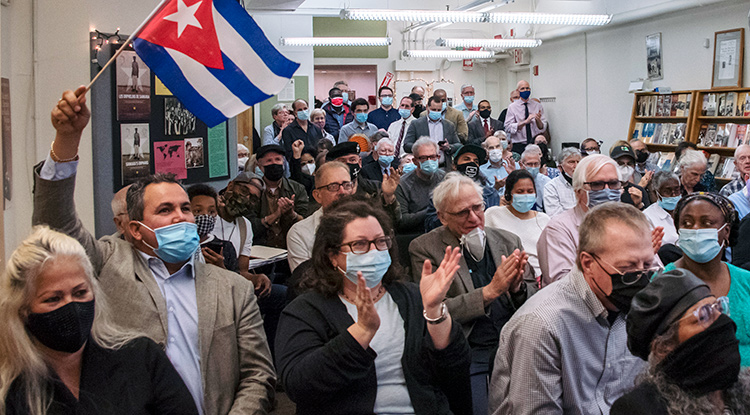

He was speaking to some 105 people at a program sponsored by the New York and Northern New Jersey Socialist Workers Party to celebrate the 60th anniversary of that historic triumph, as well as the launching in January 1961 of the yearlong campaign that eliminated illiteracy in Cuba. The talks, messages, colorful displays and books featured at the meeting addressed several themes.

One is the continuity of the revolution’s program and course of action. It extends from the opening of the revolutionary struggle in 1953, to the Rebel Army in the mountains later that decade, to the January 1959 victory toppling the U.S.-backed Fulgencio Batista dictatorship. It continued through the mobilizations of workers and peasants that nationalized the land, banks, and factories, to Fidel Castro’s call to arms to defend the socialist revolution on the eve of the Bay of Pigs invasion, to the revolution’s proletarian internationalism shown today by its active solidarity with peoples the world over in face of the COVID pandemic.

A second theme is that Cuba shows socialist revolution is not only necessary but, with a conscious and disciplined working-class leadership, can be made — and defended. It is the only realistic perspective for working people in the United States.

Participants in the event included Cuban Americans from both sides of the Hudson River who’ve taken part in car and bike caravans in New York City demanding an end to Washington’s decadeslong economic war against Cuba. There was a young hardware store worker from New York City, as well as a worker at a graphics shop in the Albany area. There were college and high school students from New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Workers at several Walmart stores in the region attended, as did rail freight conductors, nurses and other workers. There was a radio host for a station in Orange, New Jersey, connected to a large Pentacostal church, that broadcasts interviews and other news to Haitians on the island and here, including information about the Cuban Revolution.

SWP members and supporters came from Albany, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C. A delegation from the Frente Independentista Boricua, a Puerto Rican independence group, took part, as did a Venezuelan-born physician trained at a Cuban medical school, now practicing in the United States. A Nicaraguan psychologist visiting family in New York, who studied at a Cuban university in the late 1980s, came. And many others.

Shelves of books on revolutionary working-class politics ringed the meeting room. Enlarged covers of Bay of Pigs/Playa Girón, 1961: Washington’s First Military Defeat in the Americas by Fidel Castro and José Ramón Fernández and Cuba and the Coming American Revolution by Jack Barnes were featured above the speakers table.

Along with Ambassador Pedroso, speakers included Mary-Alice Waters, a member of the SWP National Committee and author or editor of many books on the Cuban Revolution, including interviews with its leaders, as well as Catherine Murphy, director of The Literacy Project. Murphy, who participated via video hookup from San Francisco, also shared a preview from her forthcoming documentary on Cuba’s literacy campaign, Maestros voluntarios (voluntary teachers).

Joanne Kuniansky, SWP candidate for governor of New Jersey and a deli counter worker at Walmart, welcomed participants to the celebration, held at the party’s New York City headquarters. Kuniansky described the receptivity she and other SWP candidates find as they campaign on working people’s doorsteps, build solidarity with strikes and other labor struggles, join in social protests, and present working-class answers to today’s widespread joblessness and other crises of the profit-driven capitalist system. At the close of the meeting, Kuniansky introduced the other SWP candidates in attendance.

The program was chaired by New York SWP member Martín Koppel, who is active in the local Cuba Sí coalition and a Pathfinder Press editor. “In Cuba, too, millions are celebrating these anniversaries,” he said, “including during the congress of the Cuban Communist Party taking place right now.”

Koppel introduced the delegation from Cuba’s U.N. mission, which, along with the ambassador, included first secretaries Ena Domech and Karell Lussón. Koppel also recognized Cuban Americans in the audience who’ve joined caravans against Washington’s embargo, as well as a number of other individuals, including Jack Barnes, Socialist Workers Party national secretary.

‘A genuine revolution’

“Successive U.S. administrations have denied the fact that the Cuban Revolution is a genuine process born out of the Cuban people,” Ambassador Pedroso said. But what the Cuban people did 60 years ago at Playa Girón belies that claim.

“Our revolution was not imported or invented by a group of young dreamers,” the ambassador said. “The revolution, the literacy campaign, and the victory at Playa Girón were the result of years of struggle against Yankee interference and the blunder of neocolonial governments and bloody dictatorships that ignored the needs of the Cuban people,” who confronted “rampant illiteracy, malnutrition, unemployment, prostitution, drugs and gambling casinos.”

At the end of the meeting, as part of a toast by participants to these victories, the ambassador raised his glass and said: “For another Girón, this time of a huge international movement to defeat the blockade!”

In Fidel Castro’s September 1960 address to the U.N. General Assembly, Catherine Murphy pointed out, he announced that Cuba would eradicate illiteracy in the coming year. Ensuring that the island’s entire population — whether 85 years old, or only 8 — learned how to read, write, and figure was “a core pillar” of the revolution’s program, Murphy said. It had been ever since Castro’s 1953 defense speech in the courts of the U.S.-backed tyranny — a speech that was printed and circulated in the hundreds of thousands under the title History Will Absolve Me as part of the revolutionary struggle that triumphed six years later. Murphy held up a copy of that historic program, noting that Pathfinder had published it in English translation.

Some 100,000 young people under age 18 volunteered in 1961 for nearly yearlong brigades, fanning out mostly to rural and mountain areas. The clip from Murphy’s new video explained that these young people not only conducted classes but took part in daily farm tasks, vaccinated children, taught basic health measures, registered those without birth certificates, conducted marriage ceremonies and more.

It was a popular, proletarian mobilization only possible in the course of a socialist revolution, transforming not only the brigadistas but the peasants and other working people they were both teaching and learning from. Altogether, a quarter million Cubans volunteered for the literacy campaign.

The Cuban leadership was confident they could meet this seemingly impossible goal, Murphy said, because of what working people had already done, starting with the sweeping land reform nearly two years earlier. Moreover, starting in April 1960 hundreds of volunteers had already been teaching both children and adults in the mountains. In January 1961 Conrado Benítez, a 19-year-old literacy brigadista, was murdered by counterrevolutionary bandits. The new film, Murphy said, pays tribute to the revolutionary example set by Benítez.

María de los Ángeles Vásquez, a Puerto Rican independence fighter and wife of Rafael Cancel Miranda, sent a message to the meeting. Cancel Miranda, a lifelong revolutionary and leader of the fight for Puerto Rico’s freedom, died in 2020. Copies of her greetings were featured on a display along with photos of Cancel Miranda and other Puerto Rican Nationalists being welcomed in Cuba by Fidel Castro in 1979 after their release from a quarter century in U.S. prisons.

The meeting also received a message from Ike Nahem, an organizer of the New York-New Jersey Cuba Sí Coalition.

A proletarian course for a lifetime

Mary-Alice Waters focused her comments on the importance of the road that the Playa Girón victory and literacy campaign — that is, the Cuban Revolution itself — had opened for communist workers and revolutionary-minded youth in the United States. That’s truly a cause for celebration, she said, because “without that revolutionary political course, we wouldn’t be here today.”

For those in the room who had lived through those days in April 1961 — and “I count myself among them,” Waters said — those events “defined us and set a course of action for a lifetime.” At the time, Waters said, she was “a green, apolitical sophomore in college.” But for Waters and others like her, “the possibility of being proletarian revolutionists became totally realistic and concrete” in 1961, because of the example of the socialist revolution in Cuba.

Waters read from Fidel Castro’s speech on April 16, shortly after the first U.S.-organized airstrikes, preparing Cuba’s workers, peasants and youth for the inevitable battle they knew was coming — the mercenary invasion at the Bay of Pigs that began the very next day. “What the imperialists cannot forgive,” Castro said, is “the dignity, the integrity, the courage, the firmness of ideas, the spirit of sacrifice, and the revolutionary spirit of the people of Cuba.

“What they cannot forgive is that we have made a socialist revolution right under the very nose of the United States.”

But that affirmation by Fidel of the socialist character of the revolution wasn’t an ideological statement, Waters emphasized, but an unfolding working-class political course. And it didn’t come out of the blue. From the opening days after the January 1959 triumph, a debate had raged over whether what was happening in Cuba was a socialist revolution or — as traditional Communist Party leaderships in Cuba, across Latin America, and in the U.S. insisted — a bourgeois-democratic revolution.

On July 28, 1960, nine months before Playa Girón, Waters noted, Che Guevara had addressed an audience of thousands at the opening session of the First Latin American Youth Congress in Havana. “I might be asked whether this revolution before your eyes is a communist revolution,” Guevara said. “I would answer that if this revolution is Marxist — and listen well that I say ‘Marxist’ — it is because it discovered, by its own methods, the road pointed out by Marx.”

A socialist revolution “cannot be finessed,” Waters said. “It is the act of free men and women, of conscious men and women.” It is the product of the kind of class-struggle experience millions of Cuban working people had been engaged in well before April 1961. “The deed comes first,” Waters said. “But the deed deepens the importance of theory, of understanding what you are fighting for and why. What you are willing to give your life for.

“Without that working-class political consciousness,” Waters said, “the literacy campaign in Cuba would have been a bourgeois reform,” like those during the Mexican Revolution of the early 1900s. Not a road to unite working people in city and countryside, making it possible for them to take an increasingly greater part in running every aspect of society.

To this day, the U.S. rulers and their propagandists peddle the lie that what happened at Playa Girón was the result of vacillation by Democratic Party President John F. Kennedy and the CIA’s failure to organize adequate air support for the invasion force.

“But the battle at Playa Girón was not lost by ‘blunders,’” Waters said. “It was won by the courage and discipline of the Cuban people.”

She cited a talk by Che Guevara to an assembly of electrical workers and militia members shortly after the victory. The U.S. government’s operation “was well conceived from a military point of view,” Che said. “They did their mathematical calculations as if they were confronting the German army and coming to take a beachhead at Normandy.” They organized the invasion “with the efficiency they display in such matters.”

“But they failed to measure the moral relationship of forces,” Guevara said. They were “wrong in measuring the capacity for struggle” of Cuban working people resisting the assault.

‘Our fight is here in the U.S.’

In concluding, Waters returned to what the Cuban Revolution meant for the class struggle and for communist workers and youth in the United States.

As the Cuban Revolution was advancing, she said, the mass proletarian civil rights movement was bringing down the Jim Crow system of state-enforced segregation in the U.S. “We could begin to see the kind of social forces, the working-class forces capable of doing here what working people were accomplishing in Cuba. We could see the prospects for making a socialist revolution here, too.

“The Cuban victory at Playa Girón smashed the myth of the invincibility of U.S imperialism,” Waters said. “It showed what working people are capable of with a caliber of leadership forged in combat and, to paraphrase Fidel Castro, with the kind of sacrifices that entails.”

Waters recounted the experience of SWP leader Jack Barnes, who as a college student had spent the summer of 1960 in Cuba. Barnes participated in the Latin American Youth Conference at which Che Guevara spoke, and joined the debates about whether or not a socialist revolution was being led there. There were “interventions” by workers spreading in factories and other workplaces to halt employer sabotage. And massive working-class mobilizations that accompanied the nationalizations of U.S.- and other imperialist-owned companies.

Barnes explained to a local militia leader he had gotten to know that he was thinking of staying in Cuba to help defend the revolution from the U.S. government assault everyone knew was coming. “No. Your job is elsewhere,” the militia leader told Barnes. “We’ll take care of the invaders when they come. Your job is back in the United States, finding others like yourself who are determined to do there what we’re doing here.”

That militia leader was right, Waters said. “It gives us great satisfaction to celebrate the Cuban revolution’s victories. They are victories for all of us.

“But we never forget that our fight is here in the United States,” Waters said, “building a working-class party and movement that can take power out of the hands of the capitalist class. That, too, is what we celebrate today.”

*

Meeting participants stayed for more than a hour after the program, talking to the speakers and each other, studying the displays, purchasing books, and eating the large spread of food prepared by volunteers. In all, participants purchased 15 books, including four copies of Cuba and the Coming American Revolution.

Fidel Gómez, a Cuban living in New Jersey who participates in the caravans against the U.S. embargo, told the Militant that although he himself wasn’t born until 1969, his father and uncle fought as part of the militia at Playa Girón. “That was a big victory for the Cuban people, for the revolution, and for socialism,” he said.

Oscar Montes, a young worker at the meeting, recalled the impact that watching Maestra, Catherine Murphy’s earlier documentary on the 1961 literacy campaign, had on his thinking last year. “The Cuban Revolution was raising consciousness back then, and it’s still raising consciousness 60 years later.”

“We don’t learn about the Cuban Revolution in school,” Dakota Jarrett, a high school student from Pittsburgh, said. “We need to fight to defend it. Why wouldn’t it be possible to make a revolution here in the United States, too?”

A collection for the work of the Socialist Workers Party raised over $3,000.

Sara Lobman and Candace Wagner contributed to this article.