The Spanish edition of Women in Cuba: The Making of a Revolution Within the Revolution by Vilma Espín, Asela de los Santos and Yolanda Ferrer, three leaders of the Federation of Cuban Women, is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for June. Their interviews explain how the revolution as it progressed transformed the lives of workers and peasants and the role of women before and after the Jan. 1, 1959, popular triumph over the U.S.-backed Batista dictatorship. De los Santos said that the Second Front — the liberated zone established near Santiago as the Rebel Army advanced in 1958 — set a precedent for the workers and farmers government that followed. The extract is from the chapter “It Gave Us a Sense of Worth.” Copyright © 2012 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

BY ASELA DE LOS SANTOS

It was in the Sierra Maestra that preparations began on a large scale to teach literacy to Rebel Army combatants. It was in the Sierra Maestra that Fidel [Castro] made sure teachers were assigned to all the tiny rural schools that had been closed by the tyranny.

From the moment the Second Front was established, Raúl [Castro] had the same concern. He issued instructions stating that in all the camps, combatants who were illiterate had to be taught how to read and write. And he ordered the reopening of every small rural school that had been closed because of the war.

Carrying this out was the assignment I was given when I arrived in August.

Within the first months of the establishment of the Second Front, a wide swath of territory was liberated. After the defeat of Batista’s “encircle and annihilate offensive” by early August, those areas were largely free of Batista’s ground forces, making it possible to open more than four hundred small schools, old and new. This was also due to Raúl’s organizational capacities and to his insistence — whatever the demands of war — that there would be no neglect of something so important to the lives of the fighters and children as education. …

No one in the Rebel Army could confiscate anything from the peasants. Everything was bought and paid for. The peasants were respected. That was part of the ethical standard set by the Rebel Army. So Raúl created a group to manage finances, to manage the small amount of economic resources we had at the beginning. Out of this came a financial plan to support the expanding war.

There were also sugar plantations and mills in the area governed by the Second Front. Fidel, as commander in chief in the Sierra, ordered that for each 250-pound bag of sugar produced, the plantations had to pay 10 centavos to the movement in that territory. …

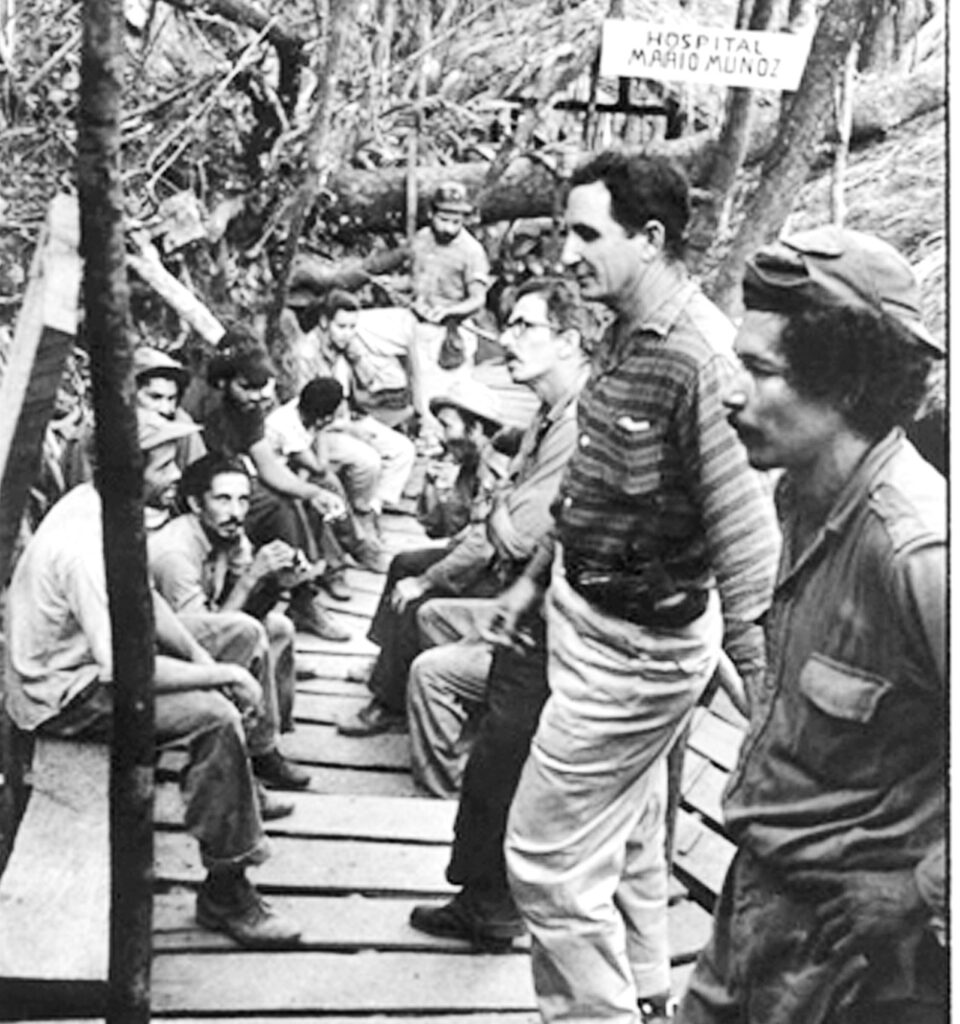

We organized hospitals and medical units. Medicine was supplied by the July 26 Movement in the cities. These units even performed surgery.

The Health Department provided health care to the population, peasants and combatants, without distinction, including wounded enemy soldiers.

For the most part, people living in the area of the Second Front had never had the chance to see a doctor before. Many had that opportunity only when the Second Front was established. For the first time they were treated like human beings.

That was the Health Department.

Another department was Propaganda. It was important politically, because we had a radio station that could be heard throughout the country. It reached as far as Venezuela. Through its transmitters, the radio station broadcast news and advanced the struggle. It refuted all the lies being spread to demoralize the Rebel Army and the people. It was also a way of communicating with the other fronts.

Then there was the Justice Department. It performed marriages and settled disputes among people in the area. It also regulated legal matters in the camps. There were even trials for misconduct. Some combatants were expelled from the Rebel Army. Discipline and order reigned in the life of the camps.

And finally there was the Education Department.

In History Will Absolve Me, Fidel denounced the existence in Cuba of widespread illiteracy. Illiteracy is a tool in the hands of the exploiters. If you are ignorant, if you don’t know how to read or write, you’re not free. Not knowing even how to sign your name makes people feel inferior.

The rural population in the Second Front was poor, exploited, hungry. Many young people joined the Rebel Army, so the number of combatants who were illiterate grew. And this was a challenge.

That’s how the education effort started. Raúl issued orders that we teach all these young combatants to read and write. …

So we set about teaching both Rebel Army combatants who were illiterate and school-age children. When peasants heard and saw what we were doing, they became interested. They asked about it. We told them that if they found the facilities, it was possible to organize small schools. So people started to look for sites, to find chairs, and to organize schools. …

So the campesinos helped open schools in locations they themselves found. After the triumph of the revolution, those new little schools remained.

In wartime you can sometimes achieve things that in normal times can’t be done so easily. In the Second Front, change was in the air. There was very little resistance there.

It’s true that in the old rural schools peasants often kept their children back. There was a high rate of absenteeism. One reason was that children went to work in the fields with their parents to sustain family income. There were other reasons also: distances that were too long, lack of shoes and clothing, and health problems.

But the new political motivation, the new hope, had a decisive influence not only on the willingness to build little schoolhouses, to make benches and improvise blackboards, but also on school attendance. This despite the danger from bombing runs by the dictatorship, which at times directly targeted civilians in murderous raids. …

A peasant congress was held in September 1958. Questions of the future were discussed, a future that was imminent — things like the right to land, the guarantee that the land belonged to those who worked it. In fact, following the triumph of the revolution, one of the first acts was the agrarian reform. More than 100,000 peasant families received titles to the land they worked.