As he moves to tighten state control over the Chinese economy, President Xi Jinping is portraying his regime and its policies as the continuation of the teachings of Mao Zedong. Mao commanded the Stalinized Chinese Communist Party, from the late 1920s through the 1949 overturn of capitalist rule and for decades afterward — a period of disastrous policies imposed on working people at home and Maoist forces abroad.

Xi’s regime fears mounting inequalities and uncertainty could lead to a rise in working-class struggles. It has curbed some profiteering by a few of the country’s private capitalists and claims to be defending socialism. His regime’s praise of Maoism is aimed at reinforcing its political authority at home as its trade and political conflicts with Washington sharpen.

Xi’s policies, like Mao’s, have nothing to do with working-class rule or advancing the class struggle worldwide.

The Chinese Communist Party was corrupted and destroyed as a communist organization shortly after its founding, at least two decades before the 1949 revolution. Maoism has its roots in the degeneration of the Russian Revolution at the hands of growing bureaucratic petty-bourgeois layers in the Soviet state headed by Joseph Stalin.

Under the leadership of V.I. Lenin and the Bolshevik Party, workers and farmers were led to take power in Russia in 1917, inspiring a wave of revolutionary struggles worldwide and the growth of the world communist movement. But in less than a decade workers and peasants were driven from power in the Soviet Union in a political counterrevolution that advanced the special interests of a ruthless ruling bureaucracy. As it crystalized into a privileged caste, standing above and against the toiling majority, the bureaucracy played a reactionary role not only at home but throughout the Communist International.

Nowhere was Stalin’s overturn of Lenin’s proletarian internationalist course clearer than his directives to the Chinese Communist Party as the mighty 1925-27 Chinese Revolution unfolded.

Under the impetus of the Russian Revolution, workers and peasants in China fought revolutionary struggles against both local exploiting classes and imperialist intervention in their country. Peasants seized land. In March 1927, workers in Shanghai took over the city. But the leaders of the CCP were ordered by Stalin to lay down their arms and subordinate working-class interests to seek an alliance with the Kuomintang, the central party defending capitalist interests. Its leader, Chiang Kai-shek, then launched a massacre of tens of thousands of vanguard workers in Shanghai.

To silence opposition to the disastrous results of this course, Stalin ordered the ruthless purging of revolutionaries who had opposed this deadly policy. Mao then rose to head the party, as it was transformed into an obedient tool for the Soviet bureaucracy’s anti-revolutionary foreign policy worldwide.

Anti-working-class regime

Out of the slaughter of the second imperialist world war, the CCP still sought alliances with capitalist parties and opposed revolutionary action by working people. But confronted with the inevitable U.S.-led Korean war, Mao moved to transform the country.

The victorious Chinese Revolution of 1949, carried out using Stalinist methods that crushed any independent working-class action, freed a fifth of humanity from imperialist plunder, overturned capitalist rule and opened the door to economic development. But the CCP, consistent with its Stalinist training and outlook, came into collision with workers and farmers at every step. In a poverty-stricken country, with a party subservient to Moscow and no mass communist organization to challenge it, conditions “favored the growth of a caste on the Soviet model,” wrote Socialist Workers Party leader Joseph Hansen in 1974.

“This process had in fact already begun before 1949 in the remote rural areas where the petty-bourgeois Stalinist leaders exercised command over hundreds of thousands and even millions of peasants through the Maoist ‘Red Army,’” Hansen wrote. His article can be found in his invaluable booklet Maoism vs. Bolshevism.

As Washington drove against both the Korean and Chinese Revolutions during the 1950-53 Korean War, the Stalinist rulers in China were compelled to carry out sweeping expropriations establishing a workers state deformed at birth.

Stalinist-led defeats and disasters

In power, Mao treated working people as objects to be manipulated or savagely suppressed.

His regime decreed a “Great Leap Forward” in 1958, claiming China would rapidly surpass the industrial output of the most developed capitalist countries. It instituted forced collectivization, driving peasants off the land and into “Peoples Communes,” where their labor was mostly wasted in primitive and unproductive labor. Grain production plummeted, causing a famine and the deaths of millions.

Even with these anti-working-class policies, the CCP had tremendous prestige among oppressed peoples across the world. But Mao’s foreign policy was an extension of his actions at home. Like the regime in Moscow, his government sought an accommodation with U.S. imperialism and collaborated with other capitalist regimes to strangle any working-class struggles threatening capitalist rule, hoping to gain “peaceful coexistence” with imperialism in return.

Mao sought an alliance with Indonesia’s President Sukarno. He blocked the Maoist Indonesian Communist Party from developing a revolutionary policy to put workers and farmers in power.

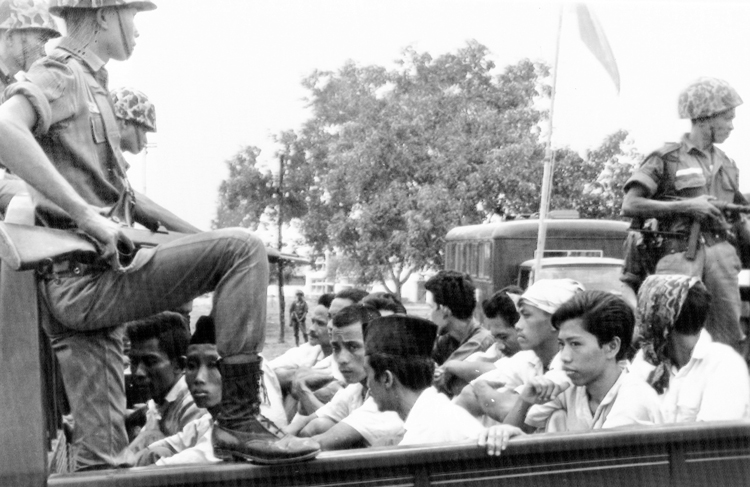

The Indonesian CP had 3 million members, and 20 million more were in organizations affiliated to it. The Indonesian army stood at only 350,000 strong. But under Mao’s orders the Indonesian CP continued to back the Indonesian regime and was left defenseless when the military turned on them and carried out the slaughter of over a million members and supporters of the party in 1965. Hansen described the massacre as “the most devastating defeat for the working-class since the fascist victory in Germany in 1933.”

When Mao’s adversaries inside the CCP moved to oust him, he launched the so-called Cultural Revolution in 1966, aimed at bolstering his rule and liquidating his opponents. He set in motion a brutal witch hunt by Red Guard youth targeting both working people and his rivals in the bureaucracy. Within a year, he turned to the army to suppress the anti-working-class movement he had unleashed by exiling many of the Red Guards to the countryside. Millions were killed or imprisoned.

Maoism became the dominant Stalinist current across Asia and beyond.

Under Maoist leadership, the ruling Pol Pot regime in Kampuchea in the late 1970s unleashed barbaric repression, forcing mass evacuations from the cities to labor camps in the countryside and liquidating anyone who it considered might stand in its way.

A sharp rift between the Stalinist parties in Moscow and Beijing opened in 1960. Two regimes with conflicting bureaucratic national interests could no longer find a common front in world politics. Moscow pulled its advisers out of China, deepening the crisis of world Stalinism and splitting Stalinist parties around the world. But neither side in the bitter dispute broke from counterrevolutionary Stalinism.

Mao increasingly feared the impact of revolutionary struggles abroad on workers and peasants in China. His regime openly sided with U.S. imperialist-backed reactionary forces during the Cold War, while continuing to mouth anti-imperialist platitudes.

Beijing turned its back on the Vietnamese people’s victorious struggle to defeat Washington’s bombardment and to reunify their country, in return for improved relations with the U.S. rulers. In contrast, revolutionary Cuba offered every assistance to the liberation forces.

Fidel Castro, the central leader of Cuba’s socialist revolution, described the Maoist regime as one of “imperialism’s brand-new allies in the camp of counterrevolution.”

“Mao Tse-tung is deifying himself,” Castro said in 1966. “Someday the Chinese people will settle accounts with its leaders.”

Xi’s identification with Maoism today will only succeed for a time in stifling working-class struggle — an inevitable consequence of state capitalist methods utilized by his regime and its predecessors. The massive expansion of industry in China has drawn millions out of the countryside and into the industrial working class, chafing at their conditions. There have been mighty explosions against Stalinist rule in China, like the mass protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, brutally repressed by the regime.

Deepening exploitation and rising social tensions will eventually drive working people to seek ways to defend themselves. This process will be greatly aided by revolutionary upsurges in other parts of the world.

In the coming battles, workers and farmers in China will have an opportunity to establish a government they can truly call their own for the first time.