For those around the world who want to unite working people to advance our class interests and to end the second-class status of women, there is much to learn from the experience of Cuba’s socialist revolution. From the very beginning, Fidel Castro led Cuban revolutionaries to advance women’s participation as equals in every aspect of society, from combat to industry.

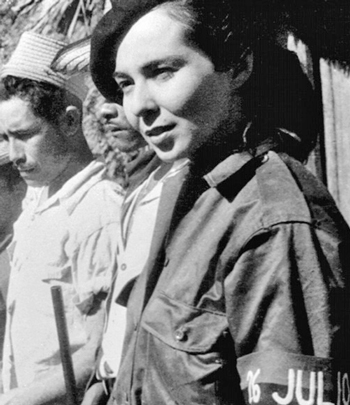

The Rebel Army and the July 26 Movement, which fought to overthrow the U.S.-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, incorporated women in both the guerrilla struggle in the mountains and the revolutionary movement in the cities. Numerous women were central to the day-to-day leadership of the battles that brought down the dictatorship.

Well before Batista fled the country on Jan. 1, 1959, the revolutionary movement began organizing working people to implement social measures in their interests in areas the Rebel Army controlled. A congress of peasants was held in September 1958 and a land reform begun. More than 400 schools were opened offering classes to the general population and the rebel soldiers alike.

Before the revolution, “beginning with the question of work, there were countless activities from which women were banned,” Fidel Castro, the central leader of the revolution, noted at the first national congress of the Federation of Cuban Women on Oct. 1, 1962.

Women “wanted to participate in a revolutionary process, whose aim was to transform the lives of those who had been exploited and discriminated against, and create a better society for all,” Vilma Espín, a leader of the revolution until her death in 2007, said in 1997.

As women joined in carrying out all aspects of the unfolding socialist revolution, they transformed themselves in the process.

The leadership did every thing it could to eliminate obstacles in the way of women’s participation, including expanding access to child care. They carried out bold practical measures and patient educational work to overcome deeply held prejudices.

Young women were a big part of the 250,000 volunteers who joined the 1961 campaign that eliminated illiteracy by teaching 700,000 people in Cuba to read in just one year. Tens of thousands shared the life of peasant families.

At the urging of Castro, the Federation of Cuban Women in 1960 set up the Ana Betancourt School for Peasant Women, which over the next few years brought 14,000 young women from the most isolated regions of the island into Havana, where they received vocational training, along with classes in reading, history, basic health and hygiene. They were introduced to the theater and ballet, widening their cultural horizons.

They were taught to sew, and given their own sewing machine on one condition — they had to make a dress for their mothers and teach 10 other peasant women how to sew. Returning home more conscious and confident, they won others to the revolution.

The revolution confronted every obstacle to women’s participation. Under a 1938 law, abortion in Cuba was allowed only in cases of rape, a threat to a woman’s life, or certain birth defects. On top of this, in the first few years of the revolution about half of Cuba’s 6,000 doctors — including the majority of gynecologists and obstetricians — left for the United States. The U.S. economic war on Cuba made it difficult to import basic contraception.

In 1965 the Health Ministry, under the urging of the Federation, issued a new interpretation of the 1938 law to permit early term abortions, which like all medical procedures was free of charge. Cuba was the first country in Latin America to decriminalize abortion. By 1979 a new penal code was adopted, and the old law was wiped off the books. Only the woman has to give consent.

The three excerpts below by Espín were printed in Women in Cuba: The Making a Revolution Within the Revolution. Copyright © 2012 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

We had to change women’s mentality — accustomed as they were to playing a secondary role in our society. Our women had endured years of discrimination. We had to show women their own possibilities, their ability to do all kinds of work. We had to make women feel the urgent needs of our revolution in the construction of a new life. We had to change both women’s image of themselves and society’s image of women.

We started our work by simple tasks that allowed us to reach out to women, to raise them beyond the narrow, limited horizons of their existence. To explain the revolution’s purpose and the part they would have to play in the process.

From the very beginning, we pursued a double goal:

To raise consciousness through political education, so that new tasks could be performed.

To raise the political level through the tasks themselves.

Speech to Second Congress of the FMC, November 1974

For us, equality is not merely a principle of social justice, but a fundamental human right. … It would be dangerous to start agreeing with the most backward capitalist ideologues on women’s participation in the workforce simply due to conjunctural considerations or because we haven’t given priority to solving the most pressing family needs.

To propose that women return to the home would be a significant step backward from all standpoints. First of all, this is absurd. It not only abandons the principle of equality and reinforces women’s traditional role; it also erases almost a century and a half of social struggle, since the pioneers of Marxism pointed to the indivisible relation between the liberation of society through socialist revolution and women’s liberation as part of the revolutionary movement. …

That’s why we’ve been careful all these years not to propose apparent solutions to women’s double burden, such as extending the length of maternity leave, giving mothers subsidies to care for their children, shortening women’s work hours, etc. Such steps, instead of reducing inequality, tend to perpetuate it by taking women out of the workforce and slowing their advancement.

“Speech at Meeting of Women from Socialist Countries,” Havana, February 1989

Since the earliest years of the revolution, the FMC has confronted serious problems arising from women’s lack of knowledge about their own bodies, their reproductive system, their sexual health, and the possibility of planning both the number of children and the time between births.

We soon won the right to have abortions included as a service of the health system, legalized under condition that they be performed by specialists and in hospitals, assuring all necessary sanitary conditions. The federation then called on the country’s health and education institutions to carry out massive educational efforts and to organize a genuine program of sexual education, open to all and based solidly on advanced scientific concepts.

Interview with Norwegian journalist, 1997