Louisiana state prison inmate Brandon Jackson was released on parole Feb. 11 after serving 25 years of a 40-year sentence. He had been charged with robbing an Applebee’s restaurant at gunpoint in 1997. Jackson’s original conviction was tainted, but that was not the reason the parole board gave for freeing him.

Despite the Bill of Rights’ requirement of a unanimous jury — which is key to ensuring the constitutional right not to be imprisoned unless found guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt” — Jackson, who is Black, was convicted by a split-jury vote of 10 to 2. The two dissenting jurors were Black.

At the time, Louisiana, Oregon and the U.S. colony of Puerto Rico allowed nonunanimous verdicts in criminal cases. In all of the other 48 states, a split jury — often called a “hung jury”— means the accused must be freed or given a new trial.

In April 2020 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution’s “right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury” — including a unanimous verdict — applies not only to federal trials but also to the states. Under public pressure, Louisiana had finally banned nonunanimous verdicts in 2019. But the court’s ruling was not made retroactive, and Jackson’s petition for a new trial is still pending.

Sheila Earls, whose son Brandon was nearing 10 years prison in 2021 after being convicted of murder in 2009 in a split verdict, spoke to the New Orleans Advocate after the Supreme Court ruling. “The people [who’ve] served 10, 20, 30 years they shouldn’t have served, you’re just going to leave them in the dungeon,” Earls noted. “They’re done. That doesn’t even logically make sense. Justice should not have a time limit.”

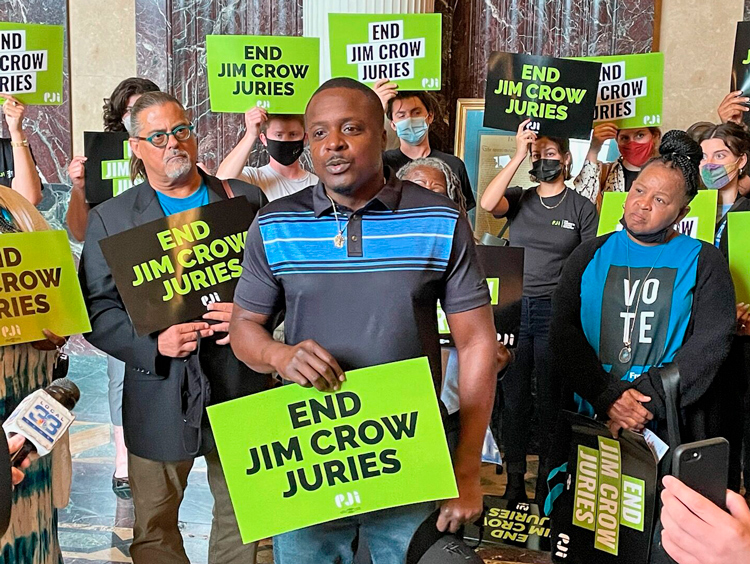

There are currently 1,500 prisoners in Louisiana, 80% of whom are Black. Hundreds in Oregon were convicted by split juries, 40% of all felony jury verdicts.

Split verdicts rooted in Jim Crow

The Louisiana state government authorized guilty verdicts if at least nine out of 12 jurors approved — it was later changed to at least 10 — in 1898 in the wake of the 1877 overthrow of Radical Reconstruction and the deepening imposition of brutally enforced Jim Crow segregation.

It was adopted by a Louisiana state constitutional convention, in their words, to “perpetuate the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon race in Louisiana.”

The dominant sectors of rapidly expanding industrial and financial capital in the U.S. brokered a deal to withdraw Union troops from the South, setting in motion an accelerating reign of terror by vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan. The bloody defeat of Radical Reconstruction in 1877 was the worst setback for African Americans and the entire working class in U.S. history.

In Oregon the split jury-verdict was enacted in 1934, during the Great Depression when there was a wave of anti-immigrant, antisemitic, anti-Catholic and anti-Asian reaction. In Puerto Rico the split-jury verdict was enacted in 1948, when the colonial government launched a wave of repression, including prosecutions against leaders of the revolutionary independence movement there.

Allowing split juries makes it easier for prosecutors to win convictions without convincing evidence. It undermines the democratic and constitutional rights of all working people, disproportionately affecting the accused who are Black.

Jackson, now 50, finally walked out of jail in Louisiana a free man after the unanimous vote by the parole board members, who pointed to his record of good behavior in prison. But he was shackled with onerous conditions, including a curfew, check-ins with his parole officer and monthly community service.

As a precondition for the parole board to free Jackson, he had to say he was guilty, even though he has always claimed his innocence.