The Great Labor Uprising of 1877 by Philip S. Foner is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for May. After five years of economic depression, West Virginia railroad workers went on strike in the face of wage cuts and brutal working conditions. This rapidly developed into a nationwide strike drawing in half a million workers, the first truly general strike in U.S. history. The rulers screamed about “mob rule” and blamed a communist conspiracy. Federal, state and city governments, cheered on by the big-business press, unleashed troops, cops and armed thugs against the strikers. In the course of this mighty class battle some 200 workers were killed. Copyright © 1977. Reprinted by permission of Pathfinder Press.

BY PHILIP S. FONER

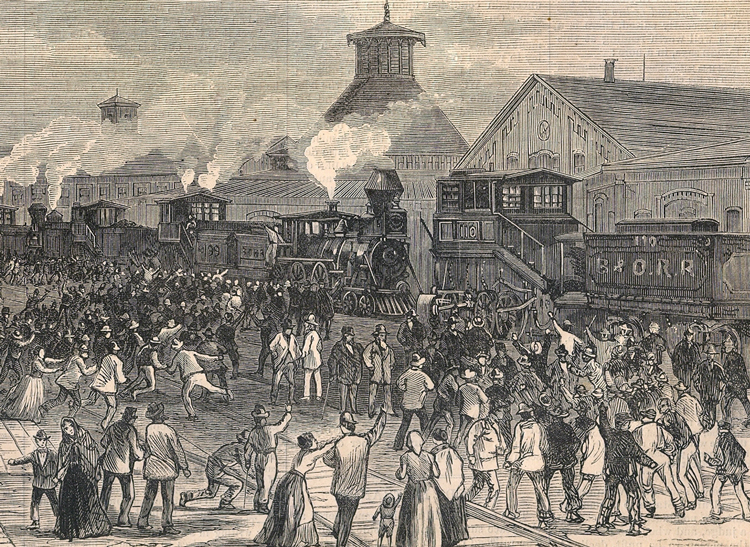

The speed with which the Great Strike moved across the country was positively breathtaking. On July 18 the strike, which had begun in West Virginia, spread to Ohio; one day later, it reached Pennsylvania, and a day after that, New York. On Sunday and Monday, July 22 and 23, thousands of workers throughout the eastern and midwestern sections of the country went on strike. By noon on Tuesday, July 24, the Great Strike had ripped through West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, and even Iowa. The New York World estimated that day that it involved more than eighty thousand railroad workers and over five hundred thousand workers in other occupations. Aside from the walkouts of workers in sympathy with the railroad men, thousands of businesses that were dependent upon the railroads for their supplies — factories, mills, coal mines, and oil refineries — were forced to shut down. …

By Wednesday, July 25, all the main railway lines were affected, and employees of some Canadian roads were also joining the strike. By this time, it was a thoroughly national event. Business in many cities was feeling the effect of the freight blockade; for example, New York’s supply of western grain and cattle had been completely cut off. There were strike reports from such scattered points as Kansas City, Chicago, Indianapolis, Terre Haute, Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, East St. Louis, and St. Louis. … Governor Cullom of [Illinois] declared in his 1879 biennial message that “the railway trains and machine shops and factories in Chicago, Peoria, Galesburg, Decatur, and East St. Louis were in the hands of the mob, as well as the mines at Bradwood, La Salle, and some other places.” …

[T]he railroad managers had proclaimed that the demand for the restoration of the wage cut was an infringement on their management rights, and they were determined not to allow the slightest interference with their total domination over the lives of their workers. In this, they were receiving the backing of the nation’s press, for those few railroad managers who had rescinded the wage cut were being pilloried as traitors to the nation. … [T]he capitalists were relying on their “puppets” in city and state governments to do the work for them of breaking the strike and forcing the workers to live at a starvation level. Thus, while they appeared to be paralyzed and helpless, their agents were drowning “the grand uprising of labor” in blood:

Already two hundred lives have been sacrificed. The military powers in different states have been used to shoot like dogs men claiming their God-given rights: at Reading, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Chicago and other points, men, women and helpless children have been massacred by citizen soldiery, employed to enforce the demands of the railroad companies. [Andrew C. Cameron, Chicago Workingman’s Advocate] …

Once the strikes were over, the Marxists [of the Workingmen’s Party of the United States] insisted that the next immediate task was to create such a national federation of trade unions, with the eight-hour day as the unifying issue. Executive committees set up during the struggle, and scattered mass meetings were not enough, they argued. Strikers with hungry families to feed required swift relief payments, and hastily established committees could not meet this need. The strikes had demonstrated the indispensability of trade unions capable of holding out against the combined employer-government offensive.

The Marxists also maintained that the strikes had also proven that skilled and unskilled, employed and unemployed, Black and white, American- and foreign-born, men and women — all could join together in a common struggle against the common enemy. Thus, it was possible to build a labor movement that would unite these different sections of the working class for the first time in American history. …

It is clear that although the strikers returned to work without wage increases, they did not return demoralized. At the end of the Great Strike, the British ambassador wrote to his government from Washington, D.C.: … “I much fear that the only result of this strike will be to show the labouring classes their strength and to enable them still further to improve for future use the organization which it has now cost so much trouble and bloodshed to subdue.” … The Great Strike … became the springboard for political and trade union action by the American working class. It was able to assume this character because it was more than a strike movement against wage cuts. It was a social rebellion, the first assertion by a national working class of a common anger against a variety of grievances — years of brutal exploitation, and a system of industrialization which viewed the worker as little more than part of the machine. … It was the first real evidence of working class collective power capable of imposing its own will upon future social developments. Workers from New York to San Francisco understood, for the first time, their potential power. …

Writing to Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx called the Great Strike “the first uprising against the oligarchy of capital which had developed since the Civil War,” and predicted that while it would be suppressed, it “could very well be the point of origin for the creation of a serious workers’ party in the United States.”