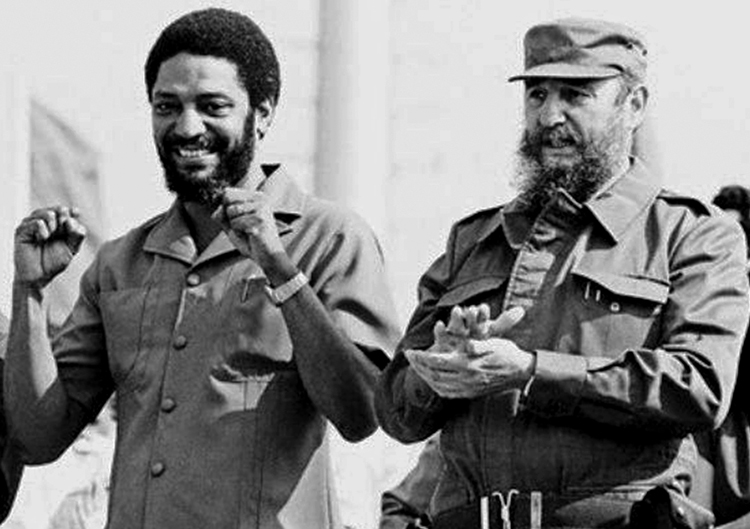

Maurice Bishop Speaks: The Grenada Revolution and Its Overthrow, 1979-83 is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for November. Inspired by the Cuban Revolution, Bishop mobilized working people to take political power in a popular revolution in 1979 on this small Caribbean island, a majority Black and English-speaking. Four years later, a Stalinist-inspired coup led by Bernard Coard murdered Bishop and other leaders of the revolution, and turned its guns on the people. The overthrow of the revolution opened the way for the U.S. rulers to invade a week later. The loss of the workers and farmers government under Bishop’s leadership was a heavy blow to Cuba’s socialist revolution. Excerpted is Fidel Castro’s speech to a million people in Havana, Nov. 14, 1983, honoring 24 Cuban workers killed during the U.S. attack. Copyright © 1983 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

In Grenada, we followed the same principle we apply to all revolutionary nations and movements, full respect for their policies, criteria, and decisions, expressing our views on any matter only when asked to do so. Imperialism is incapable of understanding that the secret of our excellent relations with revolutionary countries and movements in the world lies precisely in this respect.

The U.S. government looked down on Grenada and hated Bishop. It wanted to destroy Grenada’s process and obliterate its example. It had even prepared military plans for invading the island — as Bishop had charged nearly two years ago — but it lacked a pretext. …

Bishop was not an extremist; rather, he was a true revolutionary — conscientious and honest. Far from disagreeing with his intelligent and realistic policy, we fully sympathized with it, since it was rigorously adapted to his country’s specific conditions and possibilities.

Grenada had become a true symbol of independence and progress in the Caribbean. No one could have foreseen the tragedy that was drawing near. …

Unfortunately, the Grenadian revolutionaries themselves unleashed the events that opened the door to imperialist aggression. Hyenas emerged from the revolutionary ranks. …

[A]llegedly revolutionary arguments were used, invoking the purest principles of Marxism-Leninism and charging Bishop with practicing a cult of personality and with drawing away from the Leninist norms and methods of leadership.

In our view, nothing could be more absurd than to attribute such tendencies to Bishop. It was impossible to imagine anyone more noble, modest, and unselfish. He could never have been guilty of being authoritarian. If he had any defect, it was his excessive tolerance and trust.

Were those who conspired against him within the Grenadian party, army, and security forces by any chance a group of extremists drunk on political theory? …

In our view, Coard’s group objectively destroyed the revolution and opened the door to imperialist aggression. Whatever their intentions, the brutal assassination of Bishop and his most loyal, closest comrades is a fact that can never be justified in that or any other revolution. As the October 20 statement by the Cuban party and government put it, “no crime must be committed in the name of the revolution and freedom.”

In spite of his very close and affectionate links with our party’s leadership, Bishop never said anything about the internal dissensions that were developing. On the contrary, in his last conversation with us he was self-critical about his work regarding attention to the armed forces and the mass organizations. Nearly all of our party and state leaders spent many friendly, fraternal hours with him on the evening of October 7, before his return trip to Grenada.

Coard’s group never had such relations nor such intimacy and trust with us. Actually, we did not even know that this group existed.

It is to our revolution’s credit that, in spite of our profound indignation over Bishop’s removal from office and arrest, we fully refrained from interfering in Grenada’s internal affairs. We refrained even though our construction workers and all our other cooperation personnel in Grenada — who did not hesitate to confront the Yankee soldiers with the weapons Bishop himself had given them for their defense in case of an attack from abroad — could have been a decisive factor in those internal events. Those weapons were never meant to be used in an internal conflict in Grenada and we would never have allowed them to be so used. We would never have been willing to use them to shed a single drop of Grenadian blood.

On October 12, Bishop was removed from office by the Central Committee, on which the conspirators had attained a majority. On the thirteenth, he was placed under house arrest. On the nineteenth, the people took to the streets and freed Bishop. On the same day, Coard’s group ordered the army to fire on the people and Bishop, [Unison] Whiteman, Jacqueline Creft, and other excellent revolutionary leaders were murdered.

As soon as the internal dissensions, which came to light on October 12, became known, the Yankee imperialists decided to invade. …

Under those circumstances, we couldn’t possibly leave the country. If the imperialists really intended to attack Grenada, it was our duty to stay there. …

In Grenada, however, the government was morally indefensible. And, since the party, the government, and the army had divorced themselves from the people, it was also impossible to defend the nation militarily, because a revolutionary war is only feasible and justifiable when united with the people. We could only fight, therefore, if we were directly attacked. There was no alternative.