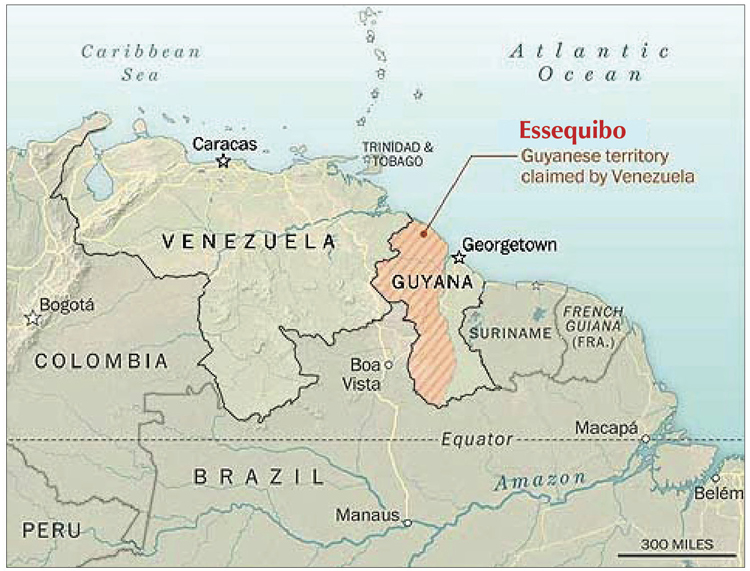

A territorial dispute between the governments of Venezuela and Guyana dating back to 1811 has come back to the fore, putting a spotlight on the danger of military conflict amid the growing instability of the capitalist world order. At issue is control over the Essequibo region, long under the control of Guyana, where large oil and mineral deposits have been found near the border with Venezuela. The oil reserves in Essequibo could make Guyana the world’s fourth-largest offshore oil producer.

In light of growing concern in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as pressure from Washington, Guyanese President Irfaan Ali and his Venezuelan counterpart, President Nicolas Maduro, met in Kingstown, capital of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Dec. 14. Their agenda was to attempt to diffuse escalating tensions over Essequibo.

The two governments released a joint statement saying they “will not threaten or use force against one another in any circumstances” and “will refrain, whether by words or deeds, from escalating any conflict or disagreement.”

The dispute had escalated after the Maduro government held a national referendum Dec. 3 calling on voters to agree with steps by Caracas to reclaim sovereignty over the area. The vote was held despite a warning from the United Nation’s International Court of Justice to refrain from any action challenging Guyana’s long-standing control over the territory. The vote was marked by low turnout, the press reported, despite Maduro’s efforts to mobilize support.

Over two centuries, the territorial dispute has ebbed and flowed as Venezuelan politicians have used it to rally nationalist support for their rule. The main bourgeois opposition figure in Venezuela’s upcoming 2024 presidential election, María Corina Machado, accused Maduro of trying to distract attention away from the current economic and social crisis in Venezuela, while joining in pledging to defend Venezuela’s territorial claims.

The Essequibo region comprises more than two-thirds of Guyana’s territory and 16% of its population. In 1811, when Venezuela proclaimed its independence, the new government there claimed the disputed territory was within the boundaries of the former Spanish colony. The United Kingdom seized Guyana from the Dutch around the same time and eventually succeeded in bringing the Essequibo region under its control.

An international arbitration tribunal in 1899 composed of two U.S. officials, two from Britain and one from Russia ruled 3-2 to grant the British rulers control over 94% of the disputed territory.

The Essequibo dispute was rekindled in 1966 when Guyana won its independence.

Venezuelan President Maduro’s sabre rattling has increased tensions in the region. He announced shortly after the national referendum that his government would grant operating licenses for oil exploration and exploitation in Essequibo and create a Comprehensive Operational Defense Zone over the disputed territory. His government says it’s clearing land there to create an airstrip.

The Guyanese government denounced the referendum as a pretext for a land grab and says its borders are not up for discussion. “Should Venezuela proceed to act in this reckless and adventurous manner, the region will have to respond,” President Ali said Dec. 6.

Threat in the region

Guyana’s 4,000-strong armed forces are no match for Venezuela’s military, which numbers over 120,000 troops.

The Venezuelan government has bought large quantities of heavy weapons from Moscow, Beijing and Tehran, making it one of the most heavily armed countries in Latin America.

Following the Essequibo referendum, Maduro gave foreign companies operating there 90 days to register under Venezuelan law or pull out. In September, Guyana received bids for eight of 14 offshore oil and gas exploration blocks it offered for auction, including from Hess, Arabian Drilling Co., and Watad Energy, the last two connected to Saudi Arabia.

Exxon Mobil operates its largest foreign oil project in offshore Guyana. China National Offshore Oil Company is a 25% partner in this Exxon-led consortium.

While Beijing maintains close relations with Caracas, in the last decades it has also sought to deepen diplomatic and trade relations with the Guyanese government, pursuing infrastructure and mining projects.

For its part, Washington would “stand in Guyana’s corner when it comes to threats to its territory and sovereignty,” Nicole Theriot, Washington’s ambassador to Guyana, told the press. The U.S. Southern Command conducted “routine” joint flight operations with Guyana’s defense forces Dec. 7.

Response in Latin America

“If there is one thing we don’t want here in South America it’s war,” Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said in response to the growing threats. Brazil’s officials have reiterated the “inadmissibility” of acquiring territory by force, and deployed 600 soldiers and armored vehicles to its northern border to block the only paved road running from Venezuela to Guyana through the dense jungles. Brazilian state-controlled oil company Petrobras has also placed bids for development in Guyana.

Maduro’s threatening moves are running into political difficulty with the stated positions of leaders of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), which has declared the region a “Zone of Peace.”

Guyana has sought support from the Caribbean Community, Caricom, which along with representatives of Brazil, Colombia, the U.N., and CELAC was present at the Dec. 14 meeting in Kingstown.

Guyanese President Ali called for Cuba to help mediate the dispute.

Cuba, a leading member of CELAC and Caricom, has ties with Guyana that go back decades. In the early 1970s, along with three other English-speaking newly independent former British colonies — Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago — Guyana established diplomatic ties with Cuba, despite Washington’s pressure.

In late 1975, as imperialist-backed South African apartheid forces were moving toward Luanda, seeking to crush Angola’s newly won independence, the Cuban revolutionary leadership responded to requests from Luanda and sent combatants to stop the offensive. Cuba approached several Caribbean countries for permission to refuel its planes transporting troops and materials. The government in Guyana made facilities available.

President Fidel Castro and other Cuban leaders defended Guyana’s territorial integrity when in the past it was threatened by Venezuela’s capitalist rulers. Havana has extended support to both Guyana’s and Venezuela’s economic and social development.