Below is the introduction to the new book, The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party by Jack Barnes. Barnes is the national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party. Copyright © 2019 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party is about the working-class program, composition, and course of conduct of the only kind of party worthy of the name “revolutionary” in the imperialist epoch. The only kind of party that can recognize the most revolutionary fact of this epoch — the worth of working people, and our power to change society when we organize and act against the capitalists and all the economic, social, and political forms of their class rule.

This book is about building such a party in the United States and in other capitalist countries around the world. It is about the course the Socialist Workers Party and its predecessors have followed for one hundred years and counting.

“We will not succeed in rooting the party in the working class, much less in defending the revolutionary proletarian principles of the party from being undermined, unless the party is an overwhelmingly proletarian party, composed in its decisive majority of workers in the factories, mines, and mills,” emphasized resolutions adopted by the SWP convention in 1938. The party must become “an inseparable part of the trade unions and their struggles.” It must be an inseparable part of daily battles waged by the working class and other exploited producers to defend ourselves and our families against the brutal consequences of capitalist oppression.

That orientation — the course of the Bolsheviks under V.I. Lenin in leading the workers and peasants to power in October 1917 — has been our strategic course since a communist party was founded in the United States two years later, along with others affiliating to the new Communist International. The new party had one sole aim — emulating the Bolsheviks’ example. The SWP is the direct descendant of that party.

With the rise of industrial capitalism some two hundred fifty years ago, conflicts between workers and employers increasingly took on “the character of collisions between two classes,” explained Karl Marx and Frederick Engels in the Communist Manifesto, the founding program of the revolutionary workers movement. In face of the capitalists’ cutthroat drive for profits, workers have no choice but to “club together in order to keep up the rate of wages” and resist employers’ push to extend the workday and speed up production, with cold disregard for our health and safety. Inevitably, workers “begin to form combinations (trade unions)” against the employing class.

Some two centuries of class-struggle experience have confirmed that such “combinations” take many initial forms — from acts of resistance on the job; to battles against company lockouts; to strikes, organizing drives, and campaigns to expand union power.

The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party is a new edition of the book first published in 1981 under the title The Changing Face of US Politics: Working-Class Politics and the Trade Unions. It is intended to be read, and above all used, as a guide to building a revolutionary workers party. Along with documents from earlier editions selected to focus on fundamental questions at the heart of the Socialist Workers Party’s turn to industry from the 1970s on, it also includes three new pieces that give further concreteness to these reports.

The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party is a new edition of the book first published in 1981 under the title The Changing Face of US Politics: Working-Class Politics and the Trade Unions. It is intended to be read, and above all used, as a guide to building a revolutionary workers party. Along with documents from earlier editions selected to focus on fundamental questions at the heart of the Socialist Workers Party’s turn to industry from the 1970s on, it also includes three new pieces that give further concreteness to these reports.

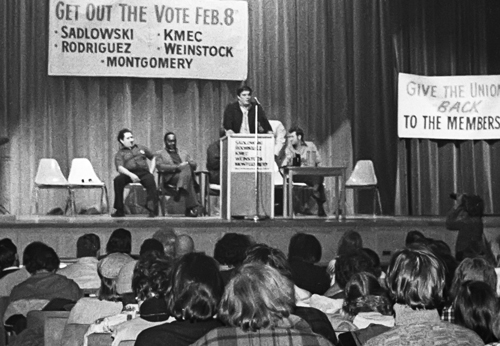

Two of them are from the pages of the Militant newsweekly — one on the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign of the mid-1970s, the other a column by party veteran Marvel Scholl entitled “The Making of a Union Bureaucrat.” The third is from a February 1980 report by Ken Shilman, who organized the work of party members in the United Mine Workers union at the time, drawing a balance sheet on the first two years of party building and trade union activity in the coalfields of West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Alabama.

During the 1960s the SWP and its affiliated youth organization, the Young Socialist Alliance, had grown rapidly, recruiting large numbers of new members who had been won to the revolutionary working-class movement as students fighting Jim Crow segregation — North and South — as well as organizing against the Vietnam War and the oppression of women. In February 1978 the party’s National Committee adopted the first report in this collection, “Leading the Party Into Industry,” and began a historic turn.

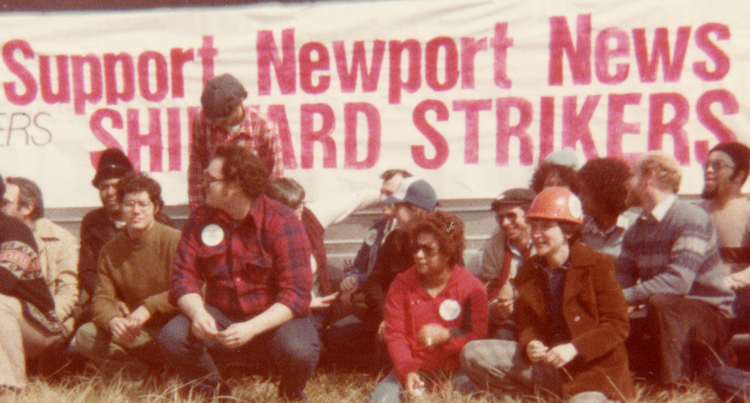

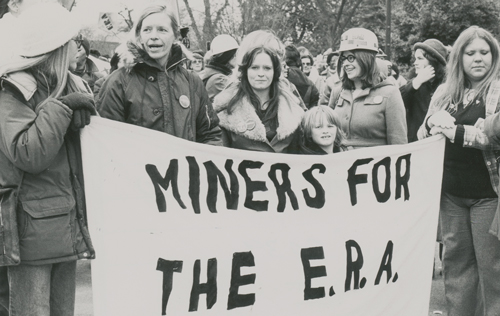

Members of the party responded with enthusiasm, as well as disciplined attention to every detail. By the mid-1980s the large majority of party members were carrying out union and political work alongside other workers in auto plants, steel mills, rail yards, coal mines, oil refineries, electrical equipment factories, garment shops, textile mills, packinghouses, airports, and other industrial workplaces. Readers will find the breadth of this activity captured in the reports and the new and greatly expanded photo pages throughout the book.

Over the years since the SWP made what has become known as the turn to industry, the imperialist order has sunk into deeper and deeper crisis: declining profit rates; intensifying global capitalist competition; stagnation in capital investment to expand plant, equipment, and industrial employment; mounting pressures toward currency wars; and unending military conflicts. Workers and our families face attacks by the capitalist class, its government, and its Democratic and Republican parties, with their “socialist” wings, on our living and job conditions — on our very life and limb.

The rulers’ blows don’t fall evenly or with the same force on all sections of working people. Inequalities are widening not only between social classes but within the working class itself.

In face of these unrelenting assaults, the working class and labor movement have been in retreat since the 1990s, one symptom of which has been the sharp decline in union organization. Union membership in privately owned workplaces has fallen from more than 20 percent when the reports in this book were given to 6.5 percent today. The drop has been steep among industrial workers — from 87 percent of underground coal miners in 1977 to some 20 percent in 2018; from more than 90 percent of automobile workers in the late 1970s to some 50 percent today; with comparable trends among other mining and manufacturing workers.

But the necessity — and opportunities — for working people, nonunion and union alike, to be bold, to organize ourselves, and to mobilize mutual solidarity have seldom been greater. And necessity is pushing us in that direction. The measure of our success will often not initially be the formation of new and powerful unions fighting for the interests of our class.

It will be the experience and confidence workers gain as we act together.

It will be the experience and confidence workers gain as we act together.

It will be our increasing political knowledge and consciousness of the employers — and of ourselves.

It will be our pride and our readiness to stand up and be counted as we act together as part of a common class.

And it will be our deeper understanding, explained by Engels as far back as 1847, that “communism is not a doctrine but a movement; it proceeds not from principles but from facts.” It is the line of march of the working class toward political power.

Socialist Workers Party members today work and fight alongside rail workers — freight conductors to yard workers — confronting concession contracts, cuts in crew size, and increasingly dangerous job conditions as a result of the carriers’ profit drive. We work and fight alongside workers at large retail stores owned by Walmart, the biggest private employer in the United States, with a nonunion workforce of some 1.5 million. We carry out political activity with car service and taxi drivers — from Africa, Asia, North America, and elsewhere who are working longer and longer hours under conditions of plunging take-home pay, unsustainable debt, and rising suicide rates in face of cutthroat competition among them fostered by owners of the fleet companies and “gig economy,” “woke” capitalists.

The workers most open today to acting against the employers and to giving consideration to working-class political alternatives are those the capitalist families and the professional and upper middle classes dismiss as “deplorables” or smear as “criminals” or just “trash.” Those contemptuous slurs are the opposite of the Socialist Workers Party’s knowledge of the big majority of our class. We consider them a better class of people. We come from them. We’re part of them.

These are men and women of all skin colors and ages. They and their kin come from urban and rural backgrounds, from all continents and national origins. It is among these “deplorables” that a disciplined and fighting union vanguard of the working class — and above all a tested class-conscious political vanguard, independent of the Democratic and Republican parties — will be forged and steeled over time in struggle against the employing class.

❖

The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party stands on the revolutionary continuity of the Socialist Workers Party, explained and defended some eight decades ago in In Defense of Marxism by Leon Trotsky and The Struggle for a Proletarian Party by James P. Cannon. The articles and correspondence in those two books record the successful effort to maintain a communist course in face of an opposition in the party and its youth organization that began bending to imperialist pressure and public opinion during Washington’s buildup to enter World War II.

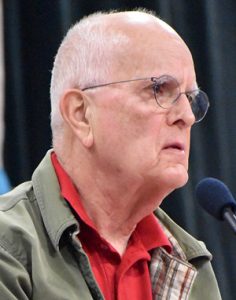

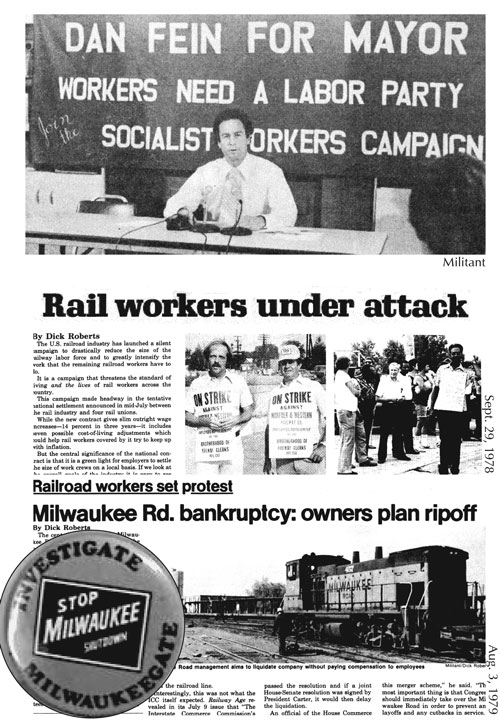

Top, Dan Fein, steelworker and SWP candidate for mayor of Phoenix, Arizona, in 1979. Above, articles in the Militant report on how Milwaukee Road rail bosses used bankruptcy courts to cut crew sizes, lay off workers and boost profits. Rail workers put out buttons and T-shirts demanding, “Investigate Milwaukeegate.”

“The opposition is under the sway of petty-bourgeois moods and tendencies. This is the essence of the whole matter,” Trotsky wrote in December 1939 in one of his articles collected in In Defense of Marxism. “Any serious factional fight in a party is always in the final analysis a reflection of the class struggle.” That’s why, as Trotsky explained in a letter written a few weeks later, “The class composition of the party must correspond to its class program.”

Trotsky had become by early 1917 a central part of the Bolshevik leadership forged by Lenin that led the workers and peasants of Russia in making the October 1917 revolution and two years later launching the Communist International. In 1929, some half a decade after Lenin’s death, Joseph Stalin banished Trotsky from the Soviet Union for leading the fight to continue Lenin’s proletarian internationalist policies. Trotsky did so in direct political opposition to the rising petty bourgeois layers in the USSR whose privileges and interests were increasingly safeguarded by Stalin. Proletarian revolutionists the world over, including Cannon and other leaders of what became the Socialist Workers Party, joined with Trotsky in founding a new world communist movement loyal to Lenin’s course.

The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party also builds on Farrell Dobbs’s firsthand account of the class-struggle leadership that organized and led workers across the Midwest in the 1930s in the strikes and union drives that transformed the Teamsters into a fighting industrial union movement. Dobbs’s four books — Teamster Rebellion, Teamster Power, Teamster Politics, and Teamster Bureaucracy — “are worth reading, rereading, and reviewing every year,” as I explain in one of the reports published here. “The more comrades get into industry, get to know the unions, and begin operating as part of party fractions, the more we’ll get out of those books every time we go back to them.”

It is also important to see The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party as a companion to three other more recent works that expand on social and class issues at the heart of America’s road to socialism:

- Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power by Jack Barnes (2009);

- Are They Rich Because They’re Smart? Class, Privilege, and Learning Under Capitalism by Jack Barnes (2016); and

- Tribunes of the People and the Trade Unions by Karl Marx, V.I. Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Farrell Dobbs, and Jack Barnes (2019).

Tribunes of the People and the Trade Unions centers on the party’s broad and systematic propaganda activity in the working class. SWP members, supporters, and young socialists support picket lines, knock on doors, and stand on porches to talk with working people in cities, towns, and farm country, as we carry out such activity on the job and in the unions. We use the Militant newsweekly, books on working-class politics, and our SWP election campaigns to explain the truth about the capitalist parties and the exploitation, oppression, and wars by capital they uphold. Above all, we report how working people are organizing to resist assaults on our rights and conditions of life and work — on the job and off.

The Militant has tremendous leverage to advance the organization and education of class-struggle-minded workers and unionists. As a “newsweekly published in the interests of working people,” which the Militant’s masthead proudly proclaims, each issue features firsthand reports by working people — written in our own voices, and in our own names — about resistance to the capitalist rulers in factories, mines, and other workplaces and working-class communities. We do so openly and boldly as who we are and what we stand for, never pretending to be anything different. And we back our co-workers in acting the same way.

Tribunes of the People and the Trade Unions also features Trotsky’s 1940 article, “Trade Unions in the Epoch of Imperialist Decay,” which, as Farrell Dobbs wrote in a 1969 preface, contains “more food for thought (and action) . . . than will be found in any book by anyone else on the union question.”

Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power, as emphasized in its very first paragraphs, explains the unbreakable link between the fight for Black freedom and a course toward the “revolutionary conquest of state power by a politically class-conscious and organized vanguard of the working class — millions strong.” A

workers and farmers government, it says, is “the mightiest weapon possible” to wage the battle to end not only racism and Black oppression but also the subjugation of women “and every form of exploitation and human degradation inherited from millennia of class-divided society.”

The introduction to that book explains why it is dedicated to SWP cadres who are African American, “who have never tired of getting in the face of race-baiters, redbaiters, and outright bigots and demagogues of every stripe who have sought to deny that workers, farmers, and young people who are Black — and proud to be Black — can and will become communists along the same road and on the same political basis as anyone else.”

❖

There is a concerted attack today on the recognition that class divisions underlie all forms of exploitation and oppression, and that class struggle and class consciousness — working-class consciousness — are central to any effective fight for liberation. The assault comes not directly from the capitalist ruling families themselves, who have always tried to hide that dangerous truth — dangerous to them.

Instead, the offensive comes from what many refer to as “the left,” liberals and radicals among the middle class and professionals — from privileged college and university campuses such as Harvard, Oberlin, and others; to prominent newspapers, magazines, and TV networks from the New York Times and Atlantic Monthly to CNN, BBC, and The New Yorker. It is promoted on websites and “social media” proliferating too rapidly to keep track of. These voices — which include individuals and political groups claiming to speak on behalf of working people and the oppressed — insist that conflicts based on race, skin color, or what they call “gender” — not class — are the driving force of history.

But the observation that the record “of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” remains as true today as it was nearly 175 years ago when Karl Marx and Frederick Engels pointed it out at the opening of the Communist Manifesto, the founding program of the modern revolutionary workers movement.

Denial of the class struggle is nothing new. There are more than enough grandparents to current “theories” about “identity politics,” “intersectionality,” and so on noisily propagated by young professionals and other upper middle class layers today. In 1940 James P. Cannon polemicized against petty bourgeois currents on the eve of World War II who “rail at our stick-in-the-mud attitude toward the fundamental concepts of Marxism — the class theory of the state, the class criterion in the appraisal of all political questions, the conception of politics, including war, as the expression of class interests, and so forth and so on.

“From all this,” said Cannon, “they conclude that we are ‘conservative’ by nature, and extend that epithet to cover everything we have done in the past.”

The epithet today is not simply “conservative,” but some variant of “homophobe” or “racist,” leveled against the working class by self-anointed “social justice warriors.” Many of them resort to slander and thuggery to intimidate those they come into conflict with, whether over political differences, relations between the sexes, or small shopkeepers merely protecting themselves from shoplifting or other depredations. Showing disdain for due process and constitutional protections conquered in class battles by workers, African Americans, women, and others, these sanctimonious inquisitors organize to smear, shout down, and silence their chosen antagonists.

The real targets, however, are tens of millions of working people across the US, whom these scornful (and sometimes newly minted) bearers of class privilege seek to drum out of the human race as ignorant, backward, racist, and reactionary. But these “deplorables” are simply the current generations of workers whom the bosses — as well as many union officials — wrote off as “trash” during the great labor battles that exploded to their shock in the 1930s.

What I wrote in Are They Rich Because They’re Smart? about today’s self-designated “enlightened meritocracy” has been confirmed many times over. This “handsomely remunerated” layer — university presidents, deans, and professors; high-and-mighty officials of “nonprofits” and NGOs; media and hi-tech professionals; entertainment and sports personalities; and many others — “is determined to con the world into accepting the myth that the economic and social advancement of its members is just reward for their individual intelligence, education, and ‘service.’” They truly believe they have “the right to make decisions, to administer and ‘regulate’ society for the bourgeoisie — on behalf of what they claim to be the interests of ‘the people.’”

But above everything else, “they are mortified to be identified with working people in the United States — Caucasian, Black, or Latino; native- or foreign-born. Their attitudes toward those who produce society’s wealth, the foundation of all culture, extend from saccharine condescension to occasional and unscripted open contempt, as they lecture us on our manners and mores.”

A few years on, the only update needed is the allusion to their open contempt being “occasional” and “unscripted.” Today it’s both frequent and intentional.

❖

Working people have nothing to gain and everything to lose by relying on the propertied families, their capitalist two-party system, their “socialist” water carriers among professionals and the upper middle class, and their government and state. We must organize ourselves independently, both politically and organizationally, of the propertied classes who derive their enormous wealth and power from exploiting the social labor of workers, farmers, and other toiling producers — and who above all work to conceal that reality from us in order to retard the development of class consciousness.

Today, the program and course of action presented in The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party are needed by working people whether fighting for unpaid wages in a mine in Kentucky; organizing to resist unsafe working conditions in a massive retail conglomerate or on a two-hundred-car freight train; defending a woman’s right to choose abortion; demanding amnesty for undocumented immigrants; mobilizing against cop brutality; or organizing solidarity with struggles by working people anywhere in the world.

Class-conscious workers openly and boldly join in every fight, every “combination” we can to resist the bosses’ assaults, whether or not we’ve yet forged a union in our workplace.

We join in the pressing task of rebuilding and strengthening the labor movement, taking part in and championing efforts to organize the unorganized wherever workers are fighting, whatever the official status of their “papers.”

And we explain the need for and help advance class consciousness, which unites not divides us, as we begin to transform ourselves and the trade unions into instruments of struggle against capitalist rule and exploitation itself.

There are no guarantees about what percentage of our class will become organized into unions, or how many unions will be transformed. “We’re not prophets but revolutionaries who work to steer developments in the direction of strengthening the unity of the working class in struggle,” notes the report in these pages that draws lessons the SWP learned from the first year of our turn to industry.

In the two great socialist revolutions of the twentieth century — in Russia in 1917, and then some four decades later in Cuba — the centrality of trade unions and the fight to transform them came largely after, not before, the struggle for workers power. But revolutionary-minded workers can’t bank on that pattern being repeated in today’s world, in which both the level of industrialization and the size and weight of the working class are much larger, not only in imperialist countries but also many others.

One thing we know for sure, however, is that a socialist revolution in the United States is inconceivable without organizing our class to fight to build unions and to use union power to advance the interests of working people here and around the world. And the forging of a proletarian party — a revolutionary political instrument of the working class, aimed above all at changing which class is exercising state power — is impossible without participating in that struggle.

The biggest obstacle to class consciousness is what all the institutions of capitalist society teach working people to think of ourselves. What we’re taught about our worth as human beings. What we’re told we’re not capable of doing and never will be. What we’re lectured about day in and day out by the bosses and their middle class “experts” and “regulators,” much of it echoed by union bureaucrats.

But the class struggle has a different story to tell. Malcolm X, Ernesto Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, Maurice Bishop, Thomas Sankara, and other outstanding revolutionary leaders never tired of reminding working people why discovering our worth is more important than harping on our oppression and exploitation. Of explaining what we are capable of becoming. And of showing us in action how we are capable of transforming ourselves — and the foundations of society itself — as we organize together and fight.

It is through such class battles, which include all social and political struggles in the interests of working people, that we gain experience and confidence, in ourselves and in each other. It’s how ties of class solidarity and loyalty are forged. The SWP’s program adopted in 1938, and still guiding our course today, tells the truth as well as it is possible to do:

“All methods are good that raise the class-consciousness of the workers, their trust in their own forces, their readiness for self-sacrifice in the struggle. The impermissible methods are those that implant fear and submissiveness in the oppressed in the face of their oppressors, that crush the spirit of protest and indignation or substitute for the will of the masses — the will of the leaders; for conviction — compulsion; for an analysis of reality — demagogy and frame-up.”

There’s nothing to add today to the closing sentences of that program. The Socialist Workers Party “uncompromisingly gives battle to all political groupings tied to the apron strings of the bourgeoisie. Its task — the abolition of capitalism’s domination. Its aim — socialism. Its method — the proletarian revolution.”

September 27, 2019