This month marks the 56th anniversary of the historic voting rights march from Selma, Alabama, to the state’s capital, Montgomery. Together with the 1956 Montgomery bus boycott and 1963 Battle of Birmingham, these actions were high points in the proletarian-led civil rights struggle that overturned Jim Crow segregation.

This victory changed the course of U.S. history, strengthening the fighting capacities of the working class that nothing short of a counterrevolution could reverse. There is less racism today among working people than ever before.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had been organizing efforts to win the vote for Blacks in Selma and surrounding Dallas County. Blacks made up the majority of the population but only 2% were registered. By early February 1965 over 3,400 demonstrators demanding the right to vote were jailed. On Feb. 18 state troopers attacked SNCC-led activists in Marion, shooting and killing protester Jimmie Lee Jackson.

In the midst of this, Malcolm X visited Alabama to meet with young civil rights fighters. After addressing 3,000 students Feb. 3 at Tuskegee Institute, a university in Tuskegee, members of SNCC invited him to nearby Selma the next day.

Addressing 300 youths at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church Feb. 4, Malcolm offered his assistance to SNCC. He put the fight for Black rights in a world context, saying, “I pray that you will grow intellectually, so that you can understand the problems of the world and where you fit into, in that world picture.” He said a Klan segregationist hiding behind white sheets “is nothing but a coward,” and “the time will come when that sheet will be ripped off. If the federal government doesn’t take it off, we’ll take it off.”

SNCC and Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference decided to organize a march from Selma to the state Capitol in Montgomery to demand arch-segregationist Gov. George Wallace protect Blacks registering to vote. Wallace ordered state troopers “to use whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march.”

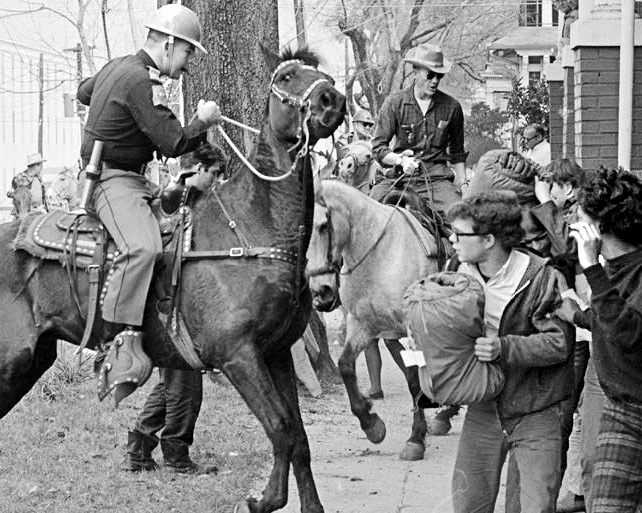

When the protesters set out March 7 they were ruthlessly attacked by the troopers and sheriff’s deputies, who used clubs, tear gas, whips and rubber tubing wrapped with barbed wire to assault the protesters.

That night ABC-TV was airing “Judgment at Nuremberg,” a movie about the Nazi regime’s responsibility for the brutality of the storm troops in fascist Germany and the Holocaust. Nearly 50 million people were watching. The station interrupted the broadcast to show filming of the racist brutality in Selma.

There was an immediate reaction. Protests in solidarity with the voting-rights marchers took place across the country. SNCC and SCLC called for volunteers to come to Selma and Montgomery to fight for the right to march on the capital.

On March 15 President Lyndon Baines Johnson spoke before Congress, saying he was going to submit a voting rights bill. A federal court ruled the march could take place. Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard and ordered it to protect the participants. The march, swelling to over 25,000, reached Montgomery March 25. The Voting Rights Act was signed on Aug. 6.

An inspiring example

The mobilizations in Selma and Montgomery “were an inspiring example of the determination and willingness to fight by Blacks there, and volunteers like myself responded to the call to join them,” Militant editor John Studer said in an interview. At the time Studer was an 18-year-old student at Antioch College in Ohio, and a member of the Antioch Committee for Racial Equality. Studer and others from the school and the nearby historically Black college of Wilberforce jumped in their cars and drove down.

“When we got to Montgomery we joined in the daily protests, and in big church meetings each night where what to do next was debated,” Studer remembers. “A sheriff’s posse on horseback went after us with clubs on one of the marches, but we were able to retreat into the Black community, which they didn’t have the nerve to go into.”

On March 15 when Johnson gave his speech announcing support for passage of voting rights legislation, “I watched it on TV with dozens of others crammed into a house in the Black community in Montgomery,” said Studer. “We laughed when Johnson felt the pressure to use the slogan of the civil rights movement at the end, saying, ‘We shall overcome’ in his sharp Southern drawl.

“But everyone knew that coming from a Texas segregationist political figure it showed how powerful the mass mobilization led by Black working people was and the impact it was having throughout the country.”

Covering these developments at the time, the Militant called for sending federal troops to Alabama to protect Blacks’ constitutional rights, for the arrest and removal from office of local officials who sanctioned the bloody assaults, and for the federal government to arm and deputize Black citizens there to defend themselves.

On March 21 court orders allowed protesters to begin their four-day 54-mile Selma to Montgomery march.

Nearly 50,000 supporters — Black and Caucasian — rallied in front of the state Capitol in Montgomery when the marchers arrived.

In response to these mass mobilizations, which included support actions in many other cities and towns nationwide, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, a milestone on the road to the defeat of Jim Crow segregation.

Montgomery bus boycott

Nine years earlier the Montgomery bus boycott helped launch the modern civil rights movement. “Court Battle Reveals Turbulent Movement That Is Shaking South” headlined an article by Farrell Dobbs, writing from Montgomery, in the April 2, 1956, Militant. Dobbs was the Socialist Workers Party candidate for president in 1956 and a leader of the fight by Teamsters in the 1930s to organize a union in Minneapolis and over-the-road truck drivers throughout the Midwest.

The SWP campaigned for workers and their unions to donate station wagons so workers could get to work while boycotting the Montgomery bus system. Dobbs drove one of the first ones down. “I have seen nothing like the rank and file outpouring of grievances here since my days in the rising union movement of the Thirties,” Dobbs wrote. “Now as then, a deep well of resentment has been tapped. A burning desire to seek redress has arisen. A growing determination to get action has taken hold.”

Dobbs further notes, “If the Negro people are to win their democratic rights, if the firm alliance of the unions and the Negro movement so imperative for the unionization of the South is to be forged, then the freedom fighters of Montgomery must be supported to the hilt and all the way to their final victory.”

“We saw the same inspiring power there in 1965,” Studer said. “These powerful class battles, coupled with Blacks getting into industry and fighting for equal rights there, decisively strengthened the fighting capacity of the working class in the U.S.”