On July 29 the Weekly Standard ran an article entitled “Pig and People,” by Gary Saul Morson, a professor of Russian art and literature at Northwestern University. The article is available online. Morson develops his view that “Russia’s greatest writers, painters, and composers [of the closing decades of the 19th century] all reflected on, if they did not participate in, what one historian called ‘the agony of populist art.’”

He concludes his article: “If Russian history demonstrates anything, it is that nothing causes more evil than the attempt to abolish it altogether. The scarlet flower blooms in the Gulag. … For Russians, faith in the people’s virtue is equaled only by another belief: in the moral glory of Russian literature. That belief is warranted.”

The great Russian writers and artists were uncompromising in their artistic integrity to the truth. But contrary to Morson’s view, the glory of what the Russian artists created was defended by the proletarian Bolshevik Revolution he opposes. That glory will be taken again by new proletarian revolutions creating through generations a truly international culture — taken from the hands of the bourgeoisie, its state and institutions that promote bourgeois values.

V.I. Lenin’s evaluation of Leo Tolstoy and his esteem for the writer Gleb Uspensky (1843-1902), who is prominently presented in Morson’s article, placed the defense of their contributions in the hands of the proletarian revolution, and accurately placed their work in those decades of one of the greatest turning points in world class history.

Karl Marx in January 1860 wrote to Frederick Engels, “The most momentous thing happening in the world today is the slave movement — on the one hand, in America, started by the death of [John] Brown, and in Russia, on the other.”

The end of serfdom, differentiations in the peasantry, the explosive rise of capitalism and a modern proletariat — these were the class forces that the Bolsheviks led by Lenin would unite in revolutionary mobilizations, and the insurrection of October 1917.

In a March 1919 session of the Petrograd soviet, Lenin presented the following proletarian appreciation of Uspensky:

If you now read Gleb Uspensky — we are erecting a monument to him as one of the best writers about peasant life — you will find descriptions dating back to the eighties and nineties of honest old peasants and sometimes just ordinary elderly people who said frankly that it had been better under serfdom. When an old social order is destroyed, it cannot be destroyed immediately in the minds of all people, there will always be some who are drawn to the old.

This is in sharp contrast to Morson’s bourgeois pity for Uspensky’s character. A great artist and what his ideals bring him to: he writes that Uspensky spent his last years in an asylum. “With unrelieved guilt for his ‘swinishness’ [‘the educated Russian’] Uspensky came to believe he really was a pig and tried to turn his face into a snout.” Thus the title of Morson’s article, “Pig and People.”

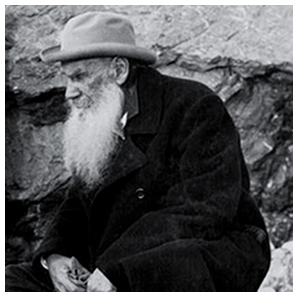

The article only makes small mention of Tolstoy.

Lenin’s November 1910 appreciation of Tolstoy, on his death, in its entirety is a powerful presentation of the class dynamic of the closing decades of the 19th century and the defense by the proletarian revolution of the great artists of that period.

A couple of excerpts:

Tolstoy, the artist, is known to an infinitesimal minority even in Russia. If his great works are really to be made the possession of all, a struggle must be waged against the system of society which condemns millions and scores of millions to ignorance, benightedness, drudgery and poverty — a socialist revolution must be accomplished.

And:

Tolstoy is dead, and the pre-revolutionary Russia whose weakness and impotence found their expression in the philosophy and are depicted in the works of the great artist, has become a thing of the past. But the heritage which he has left includes that which has not become a thing of the past but belongs to the future. This heritage is accepted and is being worked upon by the Russian proletariat.

In the next issue, the Militant will reprint Lenin’s full article, “An Appraisal of Leo Tolstoy,” and its appreciation of how the great writer described the historic class and political changes taking place in Russia.