![]() HAVANA — Un hombre afortunado (A Fortunate Man) by José Ramón Fernández, one of the Cuban revolution’s historic leaders, was presented to a packed audience at the Havana International Book Fair Feb. 13.

HAVANA — Un hombre afortunado (A Fortunate Man) by José Ramón Fernández, one of the Cuban revolution’s historic leaders, was presented to a packed audience at the Havana International Book Fair Feb. 13.

Fernández was commander of the main column of Cuban revolutionary forces that in 1961 defeated Washington’s mercenary invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. A division general in the Revolutionary Armed Forces, he carried out a variety of central leadership responsibilities, from education minister and president of the Cuban Olympic Committee to vice president of the Council of Ministers. He died in January at age 95.

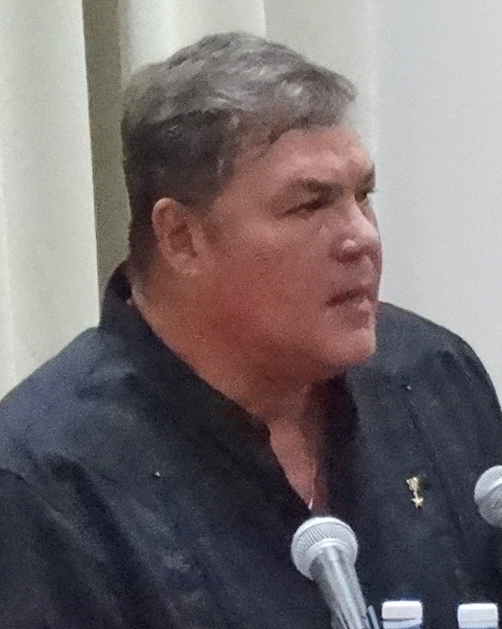

A second major presentation was held Feb. 16, featuring Hombre del silencio: Diario de prisión (A Man of Silence: Prison Diary) by Ramón Labañino. Labañino was one of the Cuban Five — as they became known internationally — who were framed up and spent up to 16 years in U.S. prisons for their actions to protect Cuba from bombings and other deadly attacks by U.S.-backed counterrevolutionaries. Today he is vice president of the National Association of Economists and Accountants of Cuba.

The presentation of Fernández’s book was a tribute to his lifelong record and example. The audience included many of those who had worked with him over the decades, as well as dozens of young members of the armed forces and military cadets. Among those present was Asela de los Santos, his wife, who was a combatant in Cuba’s revolutionary war and a founding leader of the Federation of Cuban Women.

Fernández had stressed that the book’s “main purpose was to share with the Cuban people his experiences in the battle for the revolution,” said Col. Rigoberto Santiesteban, director of Verde Olivo, publishing house of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces, which issued the book.

Abel Prieto, director of the José Martí Program and previously Cuba’s longtime minister of culture, outlined Fernández’s account of how he became a revolutionary. A young military officer in Cuba’s armed forces, Fernández led a 1956 conspiracy by a group of military men to overthrow the Batista dictatorship. He was arrested and imprisoned on the Isle of Pines (now Isle of Youth).

In his book, Prieto pointed out, Fernández explains how Fidel Castro, central leader of the July 26 Movement and the Rebel Army, demonstratively reached out to those like him who opposed the Batista dictatorship and sought to bring them into the revolutionary struggle. Fellow inmates who were July 26 Movement cadres worked closely with Fernández, and on Jan. 1, 1959, as a popular insurrection swept Cuba, they organized the release of the jailed revolutionaries.

Fernández describes his participation in the forging of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces, in the victory at the Bay of Pigs, and the variety and scope of his subsequent leadership responsibilities, Prieto said.

Also speaking at the event was Div. Gen. Ulises Rosales del Toro, a fellow revolutionary combatant and longtime Cuban leader. He saluted the revolutionary record of Asela de los Santos, which included her decadeslong collaboration with Fernández.

Labañino’s prison diary

The Feb. 16 presentation of Labañino’s prison diary also drew a standing room only audience, including many students from a high school for youth aspiring to serve in the interior ministry, which is responsible for Cuba’s state security, national police and customs. The book was released by Capitán San Luis, the ministry’s publishing house.

Labañino saluted his four comrades in arms seated in the front row — Gerardo Hernández, Antonio Guerrero, Fernando González, and René González. The book, he said, is “dedicated to the men and women of state security, of the interior ministry, who are defending our country.” The title — A Man of Silence — refers to state security officers who carry out undercover missions, as the Cuban Five did in the United States in the 1990s, whose contributions to the defense of the revolution often go unknown.

The prison diary begins in 2002, after the five revolutionaries were convicted in federal court and began to serve their sentences in different U.S. prisons. Labañino, along with Hernández and Guerrero, had been given life sentences on trumped-up charges of “conspiracy to commit espionage” and, in Hernández’s case, of “conspiracy to commit murder.”

The book shows “the dehumanizing character of the U.S. prison system,” said Labañino, who spent years at the notorious federal penitentiary in Beaumont, Texas. It also mentions the support they received from those in the United States campaigning for the release of the Five. “We know the people and the government of the United States are two different things,” he emphasized.

Among those speaking in the discussion period were two students from the interior ministry’s Hermanos Martínez Tamayo high school. Addressing all of the Cuban Five, one of them said, “You are an example for us, and for people in many countries. Thank you for being that example, which young people and our revolution need today.”