BAGHDAD, Iraq — “You must visit Al-Mutanabbi Street,” numerous Iraqis told volunteers staffing the Pathfinder Books booth at the Feb. 7-18 Baghdad International Book Fair. “And you must go on a Friday.”

So we did.

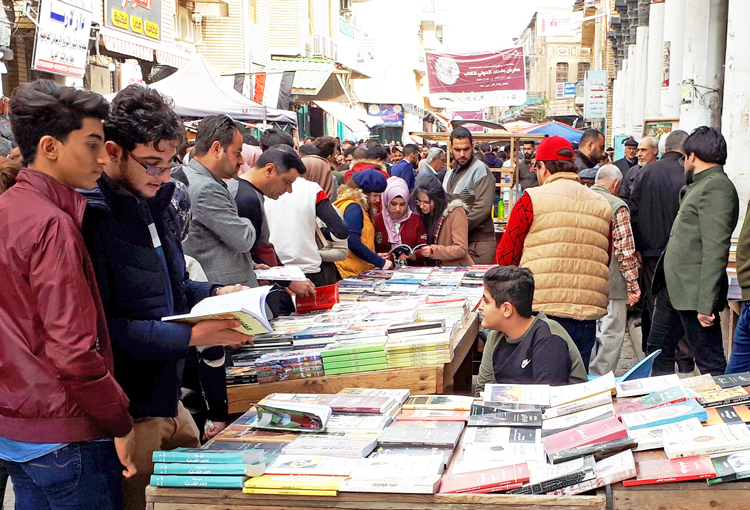

The pride in Baghdad’s historic booksellers’ district is well justified. On Fridays, the first day of the weekend here, crowds pack the street, where many buildings — like in much of Baghdad — bear the scars of decades of U.S.-organized imperialist war and of terrorism by groups pretending to speak for the Shiite or Sunni populations.

People browse the street stalls and shops displaying books of every kind, old and new, in Arabic, English and other languages. Turn into an alley and you find a courtyard with yet more bookstalls, as well as a busy outdoor cafe. Walk up the open-air stairway and you find balconies lined with publishers’ offices and — you guessed it — more bookstores.

“Al-Mutanabbi” — Abu al-Tayyib Ahmad ibn al-Husayn, for whom the street is named — was a 10th-century poet whose statue overlooks the Tigris River at one end of the road.

Nearby is Al-Qushla, a 19th-century Ottoman fort being put to much better use in the 21st century. At one spot is a crowd listening to a poet’s lively reading of his work, supported by a violinist; at another, a speaker addressing a couple of dozen people on current politics.

Afterwards, Adel Hatem told this reporter what he’d been saying. “There is a struggle going on between the U.S. and Iran, and it is taking place on Iraqi soil,” he said. “But the Iraqi people have suffered too many wars. This fight has nothing to do with us.”

The U.S. imperialist rulers maintain some 5,000 troops in Iraq, while the counterrevolutionary cleric-dominated capitalist regime in Iran sponsors Shiite sectarian militias here, above all the Hashd al-Shaabi (“Popular Mobilization Units”). Putting the Baghdad regime — already torn between dependence on both Washington and Tehran — on the spot, President Trump recently said that U.S. troops will remain in Iraq, among other things, “to watch Iran.”

Hatem told us that these speakouts and cultural events at Al-Qushla started five years ago. The opportunity to read and discuss whatever you like is not taken for granted by working people in Iraq. Faris Jejjo, who showed us around Al-Mutanabbi Street, reminded us that we were there on the anniversary of the 1963 coup that opened the way later in the decade to the Baath Party dictatorship, soon dominated by Saddam Hussein.

The coup put a bloody end to what had been a period of revolutionary upheaval. Jejjo pointed out a building where many were executed and their bodies thrown in the Tigris. The bloodletting took thousands of lives.

Decades of war and conflict

In July 1958 a coup led by Gen. Abdul al-Karim Qasim, backed by a popular insurrection, had swept the British-installed monarchy from power. The Qasim government, politically supported by the Communist Party, at first responded to mass pressure, initiating a land reform and other measures in the interest of workers and farmers. The regime soon became increasingly repressive, however, suppressing trade union and peasant struggles and waging war on the oppressed Kurds of northern Iraq. Qasim turned on his Communist Party backers, arresting many.

After the 1963 coup, all political opposition was driven underground. On Al-Mutanabbi Street we met a veteran book publisher who used to print and distribute material clandestinely for the Communist Party during Saddam’s brutal dictatorship.

That regime was ousted in 2003 through an imperialist invasion led by Washington. An unintended consequence of that assault was to open some political space in Iraq. With no reason to fear any immediate challenge to their hold on power, the occupying forces allowed political parties to function openly again, including the Communist Party.

Soon after the invasion, reactionary capitalist forces using sectarian appeals to try to turn the Sunni and Shiite communities against each other began a campaign of terror. Explosions became a regular occurrence on the streets of Baghdad.

One of these was a March 2007 car bomb that destroyed the famous Al-Shabandar Cafe on Al-Mutanabbi Street, killing nearly 30 people and injuring 100. The street was closed for a year. Mohammad al-Khashali, the owner of the cafe, who lost four sons and a grandson in the explosion, insisted on rebuilding the cafe and reopened it as the Shabandar Martyrs’ Cafe. The beautiful 100-year-old venue is known as a meeting place for writers, artists and political people to gather and exchange ideas.

As crowds thronged the streets during our visit, one group held up a banner and shouted slogans denouncing the Feb. 2 killing of novelist Alaa Mashzoub. There has been widespread outcry, including a protest organized by the Union of Iraqi Writers in central Baghdad, over the assassination of the popular author. Mashzoub was gunned down in Karbala, his home city, shortly after speaking out to criticize the Iranian rulers’ interference in Iraq.