NEW YORK — The nearly 9,000 working people imprisoned in New York City jails have little or no access to books or periodicals.

The fight to change this is part of a broader fight nationally for workers behind bars to be able to get books and periodicals of their choosing, to have access to culture and political literature.

A Feb. 26 City Council hearing brought to light some of the facts during a debate on a bill by Councilman Daniel Dromm that would allow greater jail library services. But not one newspaper, radio or television station bothered to report on it, except for the internet-based Gothamist.

Only two of the city’s 16 jails and jail hospital wards have a permanent library — the first one opened only in 2016. They are open just one day a week and prisoners are only allowed in once every two weeks.

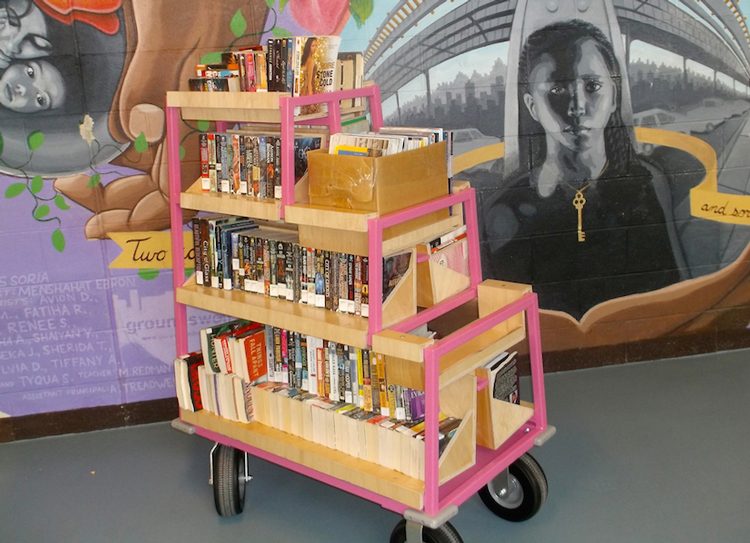

They’re the lucky ones. For the rest, New York Public Library staff in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens collaborate to send around book carts, often worked by volunteers. Prisoners are only allowed to check out two books at a time.

It’s worse for those in solitary confinement. Depending on the whim of jail officials, some in the so-called Special Housing Units are allowed to put in a written request for reading. Even then they can’t request a specific book, just the genre they would like. Then they may or may not get something.

When asked about this, one prison official callously replied that the prisoners could get books if family members buy and send them. “And if they don’t have family members?” a council member asked. The official just shrugged her shoulders.

There are still more restrictions. Books must not take up more than 1 cubic foot in inmate’s cells.

Dromm’s bill would require that corrections’ officials grant inmates daily access to a library from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m., except when they’re on “lockdown.” But it includes no funding for books or librarians and no penalties if jail officials don’t comply.

Even this is too much for jail officials. A statement from Department of Correction officials Becky Scott and L. Patrick Dail read at the hearing cynically claimed that the jailers are “open to expanding current efforts,” but oppose the bill.

Books Through Bars, New York Public Library representatives and other groups testified in favor of the bill, arguing any broader access to books would be a step forward.

Beena Ahmad from Books Through Bars said the bill allows jail authorities to censor any publications they claim “may compromise the safety and security of the facility.” This “can be a catchall that can be applied arbitrarily,” Ahmad said, and be “used to bar political books from entering prisons, such as those discussing civil rights or critiquing the government.”

The Gothamist interviewed a former Rikers prisoner, Camilla, who didn’t want her last named used. Since she was only allowed two books every two weeks, “I went through those books pretty quickly,” she said.

Camilla’s family sent her books. But when guards found her mini-library, they said it was too big and made her mail the books home.

And newspapers? Camilla said staff allowed the women in her building just one newspaper. “It was often nearly shredded with news about arrests, charges and Rikers Island literally cut out,” the Gothamist said.

Nili Ness, the Queens Library’s first and only correctional services librarian, was one of those who spoke in favor of the bill during the hearing. Three times a week she brings books to the 10-jail Rikers Island complex.

“When you work at Rikers Island, you realize how large the need is,” she told the media last year. “There are still large areas of the jail complex that don’t receive any type of library service, outside of perhaps, access to the law library.”