The successful fight waged by Gibson’s, a family-owned-and-operated bakery in Oberlin, Ohio, against a mean-spirited smear campaign by Oberlin College officials that libeled them as “racist” has entered a new stage. The college is seeking to prevent the award of legal fees ordered by the jury to the family and threatens to challenge parts of the jury’s rulings.

The decision was a victory for working people everywhere and a blow to all those who try to shut down speakers, political space and inflict damage against opponents by false accusations of “racism.”

The jury also awarded the Gibsons the largest monetary award for any libel case in Ohio’s history June 13. Their decision reflected the widespread support for the Gibson family among working people in the area, as well as anger over the disdain of college officials for the lives and concerns of ordinary people.

Judge John Miraldi denied a July 2 motion by lawyers for the college to postpone a hearing on the award of legal fees to the Gibsons for at least six weeks — one more attempt by the college to delay proceedings while they open up a fishing expedition into the small-business owner’s legal costs.

At the July 10 hearing college attorneys argued against any legal fees being awarded to the Gibsons and told the judge the college plans to appeal the award of $25 million in punitive damages.

The Gibsons’ application for attorney’s fees asks for between $9.5 million and $14.5 million, citing the length and complexity of the proceedings, and the way Oberlin College attempted to drag them out and force the family and their lawyers into “numerous unnecessary procedural and discovery motions.”

The family underwent 18 months of litigation and a six-week trial. Their application for legal fees details actions by the college’s lawyers. They took 32 depositions before the trial, including five days of questioning of 90-year-old Allyn Gibson Sr. And they subjected numerous other witnesses to multiday probing.

Eric Gaines, an African American from Oberlin who testified at the trial, said that claims the Gibsons were racist were “preposterous.” He called the college’s lawyers questioning of witnesses “a classic bullying tactic.”

“I gave a video affidavit speaking to the character of the family and the legacy in the community that they’ve had, and instead of taking that testimony on its surface for being what it is, truthful and from the heart,” Gaines said, “I get carted 30 minutes away” to “sit in a room for five hours while you dissect everything I’ve said.”

Gibson’s lawyers gave a number of other examples of this kind of bullying.

In all, “Oberlin College mounted a scorched-earth defense,” the online Legal Insurrection, which followed the case closely and backed the Gibsons, wrote July 8.

‘Pay up and apologize’

A well-known former president of Oberlin College, S. Frederick Starr, wrote in the July 6 Wall Street Journal that the Gibson’s case opposing college administrators’ “crusade” against the bakery was just. He urged the college not to fight the judgment, but to pay up and “apologize to the Gibson family and to the community.”

But instead of following this advice, college officials have launched a public campaign to misconstrue the case as a “free speech” issue. College President Carmen Twillie Ambar held meetings with CBS News, Wall Street Journal and other media, insisting the college is being held liable for the free speech of its students, with frightening implications for other institutions of higher education.

But the First Amendment and the right of students to protest were never on trial — not a single student was charged in the lawsuit. The Gibsons fought back against the orchestrated race-baiting slander and boycott of the family business by the college. And, as a devastating 56-page factsheet by the Gibson’s legal team explains, “The right to free speech doesn’t give anyone the right to destroy reputations with false information.” Overwhelming evidence presented at the trial proved that is just what the administration did.

On Nov. 9 2016, Allyn Gibson, the son of the store owner, refused to sell a bottle of wine to a student who presented an obviously fake ID. When the student tried to walk out with two bottles of wine without paying, Gibson followed to try and stop him. Instead, he was attacked by the youth and two friends. The students involved, who are Black, later pled guilty to shoplifting, and said that no racial profiling was involved.

But over the next two days college administrators and scores of students protested in front of the store. Evidence at the trial showed that Meredith Raimondo, Oberlin College vice president and dean of students, helped organize the protest. She and another staff member went and helped pass out leaflets. In a later email, Raimondo said she had the power to “unleash the students” whenever she thought necessary.

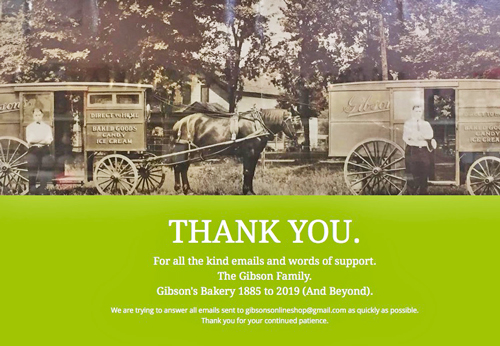

The flyers, printed for free at the college, alleged the bakery was a “racist establishment.” The trial proved the opposite — there had been no prior claims of racial profiling or discrimination during over a century of relations between the family grocery store and the campus.

The trial also revealed that despite Raimondo’s efforts to do so, she was unable to find a single African American town resident to back the “racism” smear. Despite this, the college intransigently refused to admit the race-baiting charge wasn’t true, let alone apologize. Now Ambar is promising a “lengthy and complex legal process” to try to reverse the result.

Victory for working people

The wealthy liberal college, with 2,800 students, has always dominated the town of Oberlin, where 8,000 people live. The jury pool was drawn from working people across Lorain County, near Cleveland, an area hit by years of factory closures, declining living standards and a social crisis that has included rising deaths from opioid overdoses.

David Gibson undertook the legal battle because, he wrote in a widely read column in USA Today, his father, known as “Grandpa” Gibson, was worried that although he had always tried to “to treat all people with dignity and respect,” now he was “going to die being labeled as a racist” and the Gibsons wanted to set the record straight.

They did — with broad support from working people across the region. In the days after the decision, hundreds of area workers came to the store, to congratulate the Gibsons on their victory, and, they made clear, to spend money there.