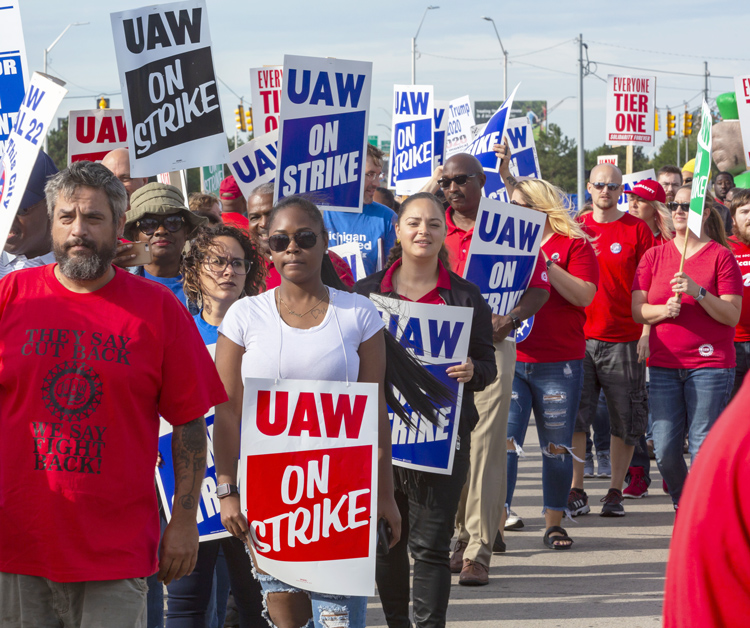

BOLINGBROOK, Ill. — The nearly 49,000 United Auto Workers union members on strike against General Motors since Sept. 16 are winning solidarity in their fight to make temporary workers permanent, as well as to get rid of two-tier wages and to force GM bosses to put workers at four plants they are shuttering back to work making cars.

Fellow autoworkers from other companies, members of other unions, workers at Walmart and others who have no union, and many more have joined them on the picket lines at the 33 factories and 22 parts warehouses on strike. They’ve brought food, supplies and solidarity to the strikers.

More solidarity is needed in the face of GM’s intransigence. The bosses claim they need more temps to compete with lower-paying nonunion auto companies like Honda and Volkswagen. They say they need more concessions to deal with cutthroat competition over coming production of electric and driverless cars. The UAW has called for beefed-up “Solidarity Sunday” picket lines until workers win a new contract.

“I started in 2006,” 33-year-old Ismael Zuniga, president of UAW Local 2114, told this Militant worker-correspondent during a solidarity visit to the picket line at the GM parts plant here Sept. 25. “I didn’t get hired on as a permanent employee until 2012 and I didn’t get full wages until this year. So it took seven years after getting on as permanent to get my full wages. I don’t want anyone else to go through the 13-year journey that I had to take.”

Temporary employees get hired for $15.78 per hour; for permanent “legacy” workers, top pay is $31 per hour. The second tier tops out at $29.90, Zuniga said.

“Temporary workers get no vacation. They get half the benefits of permanent employees. I don’t want that for my brothers and sisters,” Zuniga said. “GM has had four to five years of straight profits. Why can’t that trickle down to us?” The company’s after tax profit last year was $8.1 billion.

At GM two-tier wages were imposed in 2007. It takes eight years for new hires to approach the pay scale of “legacy” workers. With a U.S. government bailout, the U.S. auto giant carried out a carefully crafted bankruptcy in 2009, imposing further concessions. The company dumped financially troubled divisions and the pensions and health care of workers there, while cobbling together a “new” GM around their most profitable brands.

Joe Fruggiero, a Walmart worker who lives in Woodridge, joined this correspondent on the picket line and delivered a solidarity card signed by 18 co-workers to the GM strikers.

“So while the CEOs and financiers are top priority, the workers get basically nothing,” he told Zuniga.

‘They make profits on our backs’

“Yes, the CEO of GM made $22 million last year. They say they offer ‘profit shares’ but we don’t want that. We want higher wages,” said Zuniga. “It’s on our backs that they make these profits.”

There has been an outpouring of solidarity. The awning that shades picketers was donated by Chrysler workers in Belvedere. Stacks of donated food and water were piled up underneath.

UAW members from the John Deere agricultural implements plant in East Moline, members of the National Nurses Association, airline unions and the Teamsters have also stopped by. UPS drivers, organized by the Teamsters, refuse to cross the picket line.

The strikers are in high spirits because they see themselves as fighting not just for better wages and conditions for themselves, but for their fellow workers.

UAW officials say they are fighting for a “defined path” from temporary to permanent workers and to narrow the gap between tiers. Workers on the picket line don’t want to wait. On the picket line at Spring Hill, Tennessee, GM worker Keisha Montgomery sported a T-shirt that said, “Equal work, equal pay! Temp lives matter.” At many picket lines strikers hold signs saying, “No more tiers!”

Solid strike makes bosses nervous

GM claims it needs to hire temp workers and keep wages low to be more “competitive” with its nonunion rivals. It’s not only General Motors that is worried that the strike, if successful, will dent their “bottom line.” After GM, the UAW will open negotiations with bosses at Ford and Fiat Chrysler, whose contracts have been temporarily extended.

A Sept. 29 article in Automotive News, which reflects the views of the auto barons, worries that “the longer the strike has dragged on, the more expectations have grown” among autoworkers. The article complained that “years of multibillion-dollar profits by the Detroit 3 stoked eagerness to reverse past concessions.”

Bill Quigg, a leader of the fight to get a union at Volkswagen’s plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, told Business Insider Sept. 25 that because of the strike workers there who up to now have been ambivalent toward joining the fight for a union are asking questions about strikes and what the union would do if it won representation.

Kristin Dziczek from the Center for Automotive Research told the Militant that just 27 of the 57 assembly plants in the U.S. are union — making barely 50% of all cars produced in the U.S.

In 2000 just 17% of cars manufactured in the United States were assembled nonunion — by companies such as Toyota, Hyundai and Volkswagen — which pay about one-third less to permanent workers than unionized Big Three auto companies.

Broad solidarity

Three workers from Lincoln, Nebraska, joined the UAW Local 31 picket lines at the GM Fairfax plant, in Kansas City, Kansas, Sept. 28. The plant’s 2,000 UAW members produce the Chevrolet Malibu sedan and the Cadillac XT4 crossover SUV.

One of the workers from Lincoln, railroad conductor Lance Anton, a member of SMART-TD Local 305, had collected signatures on a support letter from 115 of his co-workers, including members of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen.

Railroad union members “stand with you in solidarity in your effort for a contract that UAW members can support,” the letter said. Anton said he encouraged rail crew members that make runs to Kansas City to join the picket line when they’re off duty.

“My union will soon be organizing for our national contract and we might need your help,” Anton told strikers. “If you all can get a contract you can support, that will help us.”

Jared Hayes, an electrician in training in Lincoln, like Anton, had never been on a labor strike picket line before. “Walking the picket line was inspiring to participate firsthand to see workers standing up for themselves,” Hayes said.

Workers toiling as lower paid temps, working side by side with regular workers, are increasingly common in industry worldwide.

Maintenance worker Otis Bulloch was one of a couple Walmart workers who went to the picket line at a small GM parts warehouse in Langhorne, Pennsylvania. “I was a temp for two years at a steel plant,” he said, “even though it was supposed to be only 90 days. It’s a just fight to make temps permanent.”

Joe Swanson in Lincoln, Nebraska, and Chris Hoeppner in Philadelphia contributed to this article.