The following excerpt is from Teamster Power, by Farrell Dobbs, one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for October. The title is about how members of Teamsters Local 574 learned to wield the union power forged through three 1934 strike victories in Minneapolis. Under class struggle leadership, the Teamsters extended their union throughout the Midwest, helped organize other unions and the unemployed, and strove for political independence. The book is the second volume in a four-part series by Dobbs, who emerged from the ranks to become the central organizer of the Teamster’s 11-state campaign to unionize over-the-road truckers. Dobbs went on to serve as national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party from 1953 to 1972. Copyright © 1973 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

BY FARRELL DOBBS

Workers who have no radical background enter the trade unions steeped in misconceptions and prejudices that the capitalist rulers have inculcated into them since childhood. This was wholly true of Local 574 members. They began to learn class lessons only in the course of struggle against the employers.

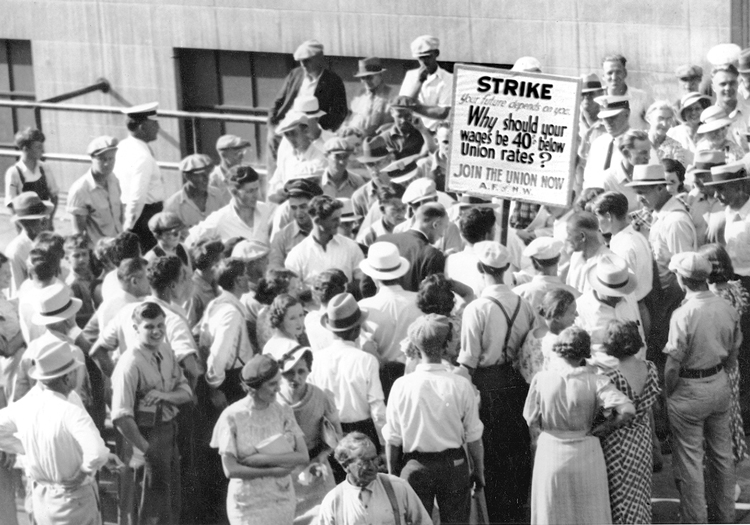

Their strike experiences had taught them a good deal. Notions that workers have anything in common with bosses were undermined by harsh reality. Illusions about the police being “protectors of the people” began to be dispelled. Eyes were opened to the role of the capitalist government, as revealed in its methods of rule through deception and brutality. At the same time the workers were gaining confidence in their class power, having emerged victorious from their organized confrontation with the employers.

To intensify the learning process already so well started, the union leader-ship now initiated an educational program. Study courses open to all members were organized. The curriculum included economics, labor history and politics, public speaking, strike strategy, and union structure and tactics. Wherever practical, officers’ reports at membership meetings were given with a view toward making them instructive as well as factually informative. Articles of an educational nature were printed in the union paper. The themes varied from analysis of local problems to coverage of events and discussion of issues in the national and international labor movement.

These endeavors stood in marked contrast to the policies of bureaucratic union officials. Bureaucrats don’t look upon the labor movement as a fighting instrument dedicated solely to the workers’ interests; they tend rather to view trade unions as a base upon which to build personal careers as “labor statesmen.”

Such ambitions cause them to seek collaborative relations with the ruling class. Toward that end the bureaucrats argue that, employers being the providers of jobs, labor and capital have common interests. They contend that exploiters of labor must make “fair” profits if they are to pay “fair” wages. Workers are told that they must take a “responsible” attitude so as to make the bosses feel that unions are a necessary part of their businesses. On every count the ruling class is given a big edge over the union rank and file. …

Local 574’s leadership flatly repudiated the bankrupt line of the class collaborationists. There can be no such thing as an equitable class peace, the membership was taught. The law of the jungle prevails under capitalism. If the workers don’t fight as a class to defend their interests, the bosses will gouge them. …

Union bureaucrats are quick to include a no-strike pledge in contract settlements and refer grievances to arbitration. The workers lose because arbitration boards are rigged against them, the “impartial” board members invariably being “neutral” on the employers’ side. Moreover, the bosses remain free to violate the working agreement at will, as grievances pile up behind the arbitration dam.

In a similar vein, conservative union officials are prone to make a general no-strike pledge when the capitalist government proclaims a “national emergency.” They do so by bureaucratic fiat, giving rank-and-file workers no voice in the decision. Such “labor statesmanship” amounts to proclaiming an overall “truce” between the workers and the bosses. Actually no truce results at all. The capitalists simply use their government to attack the trade union movement under the guise of a “national emergency”; and the workers, deprived in such a situation of their strike weapon, get it in the neck.

A development in the fall of 1934 involved this very issue. In the name of “national recovery,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked labor to forgo its right to strike. Concerning disputes with employers, he said, trade unions should accept decisions by government boards as final and binding. William Green, president of the AFL, was quick to second Roosevelt’s proposal and call upon the labor movement to put it into practice. Local 574 gave both Roosevelt and Green its answer through an editorial in The Organizer:

“Labor cannot and will not give up the strike weapon. Labor has not in the past received any real benefits from the governmental boards and constituted authorities. What Labor has received in union recognition, wage raises and betterment in conditions of work, has been won in spite of such boards. … The strike is the one weapon that the employers respect. … Whether or not there is a period of industrial peace will depend upon the employers’ reply to our demands.” (Emphasis in original.)

It did not follow from this position that Local 574 called strikes lightly. There are always hardships involved for the workers in such struggles. If the union moved blithely from one walkout to the next, without careful regard of all factors in the situation, it could easily wear out its fighting forces. The important thing is that a union stand ready and able to take strike action when required. In fact there are occasions where readiness to use the strike weapon can make its employment unnecessary.

Retention of the unqualified right to strike and readiness to use the weapon were central to the local’s enforcement of the 1934 settlement with the trucking firms. Employer attempts to impose arbitration of workers’ grievances were brushed aside. There had to be full and immediate compliance with the settlement terms — or else.