![]() The following is the presentation by Mary-Alice Waters, who spoke as part of a panel discussion in Guangzhou, China, one of some 50 during the 10th International Conference of ISSCO, the International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas. The conference was held Nov. 8-11, 2019, at Jinan University (see news article in issue no. 47 in 2019).

The following is the presentation by Mary-Alice Waters, who spoke as part of a panel discussion in Guangzhou, China, one of some 50 during the 10th International Conference of ISSCO, the International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas. The conference was held Nov. 8-11, 2019, at Jinan University (see news article in issue no. 47 in 2019).

Waters is president of Pathfinder Press and editor of Our History Is Still Being Written: The Story of Three Chinese Cuban Generals in the Cuban Revolution by Armando Choy, Gustavo Chui, and Moisés Sío Wong. The title of her presentation was, “Cultural, Diplomatic and Trade Ties between the People’s Republic of China and Cuba Today.” Participating in the audience were Cuba’s consul general in Guangzhou, Denisse Llamos Infante, and Consul Hansel E. Díaz Laborde. Copyright © 2020 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

Sixty years ago in Cuba, a century of revolutionary struggle against Spanish colonialism and U.S. imperialist domination culminated in a victorious socialist revolution. It was a deep-going popular revolution. Millions of working people of all ages, both men and women, transformed themselves as they fought for independence, for sovereignty, for dignity, and began to transform their society.

In face of military aggression and economic sabotage by Washington, supported by other imperialist powers, workers and peasants in Cuba defended and deepened their initial conquests. They established a government, and a state, of their own — one that advanced the interests of those who had been the most oppressed and exploited layers of the population.

They ended capitalist ownership of the land, mills, factories and banks. They gave land to the peasants who worked it. They outlawed discrimination based on race in all public facilities. They organized millions of women into employment and social and political activity. With a popular mobilization involving hundreds of thousands of young people, they went to the mountains, working-class barrios and rural areas, eradicating illiteracy across Cuba in less than one year. They armed the workers and farmers and organized them into disciplined militia units to defend the country they were building on new economic and social foundations.

And against all odds, for more than six decades, Cuban working people have successfully held at bay the most powerful empire the world will ever see.

Cubans of Chinese descent

For Cubans of Chinese descent, the consequences of these historic conquests have been unprecedented. One thing distinguishes the economic and the social conditions of life today for Cubans of Chinese origin from Chinese communities everywhere else in the world. That is the near total absence of discrimination or prejudice against Chinese Cubans and their descendants.

That unique condition is a stunning fact. Most of you in this room know well from your own experiences the countless forms of anti-Chinese prejudice elsewhere in the world. That alone would justify a closer look at the Cuban Revolution. In Cuba there are no typically Chinese occupations anymore, whether it’s restaurants or laundries, or small shopkeepers, or families growing vegetables and fruits for urban markets.

There’s no glass ceiling. No field of endeavor or level of leadership responsibility beyond which no one of Chinese ancestry will be found. Whether it’s government ministries, leaders of mass organizations of the Cuban Revolution, generals, artists, scientists or whatever.

Esteban Lazo, president of the National Assembly of Cuba, is a Cuban of Chinese African descent.

Lázaro Barredo, until recently the longtime editor-in-chief of Granma, the daily newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba, is a Cuban of Chinese descent.

Wifredo Lam, among the world-renowned artists of the 20th century, was a Cuban of African Chinese descent, who wove threads from those cultures into the richness of his paintings.

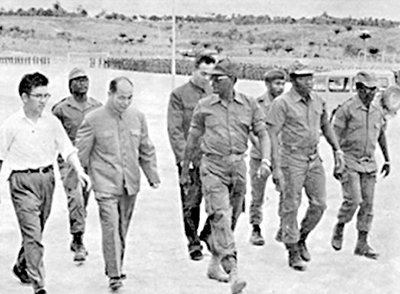

Another example — one I’ll be drawing on today, since I happen to know it best — is the three generals of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces: Moisés Sío Wong, Gustavo Chui and Armando Choy. Their stories are available — including here at the conference — in the book Our History Is Still Being Written, published in English, Spanish, Chinese, Farsi and, just this week, now in French as well.

Capitalists divide and rule

The lessons of the Cuban Revolution are especially important in today’s world of deepening capitalist crisis. Because chauvinism and xenophobia are weapons of choice wielded by the ruling classes to try to divide working people and turn us against each other. They try to convince us our problems come not from those who exploit us, but from “immigrants who take our jobs,” or neighbors whose skin color or religion is different from ours.

This is a history that overseas Chinese know well. What’s happening today in Asia, in America, in Europe, in Africa is not new. Overseas Chinese for centuries have been a prime target of attacks against “foreigners,” from the more subtle forms of discrimination and race hatred, to mob violence, exclusion laws and pogroms. This is the context in which the example of Cuba stands out.

The impact of this history on Chinese living abroad is highlighted in the foreword by Wang Lusha to Pathfinder’s 2017 edition of Our History Is Still Being Written. Wang is the young TV and film scriptwriter who translated the book into Chinese. As a university student, he studied in New Zealand and the Netherlands. In the foreword he describes encountering anti-Chinese discrimination and prejudice for the first time while living in these countries, and the feelings of inferiority it gave him.

“But one man changed my way of thinking,” Wang writes. And “that man was General Moisés Sío Wong.” Just by chance, as Wang explains, he came across Sío Wong’s name surfing the internet and read that he was a general of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Cuba and an adviser to then Cuban Vice President Raúl Castro. Wang says he thought such a thing was impossible. It couldn’t be true.

So he started trying to find out more about Moisés Sío Wong, and in the process a friend in Christchurch, New Zealand, gave him a copy of Our History Is Still Being Written.

“I felt overwhelmed as I read through the pages,” Wang noted, discovering that there were many Chinese in Cuba in addition to General Sío Wong “who made remarkable contributions.”

Learning about the Chinese in Cuba, Wang writes, restored his self-confidence and pride in being born Chinese.

No more Chinese in Cuba?

The history of Chinese in Cuba is not the topic of my presentation today. But for those of you to whom this is all new, that story began in 1847 when, over the next quarter century, more than 140,000 Chinese indentured laborers were shipped to Cuba as part of what was known as the “coolie trade.” They worked on Cuba’s booming sugar plantations under conditions very close to slavery. Many deserted the cane fields, joined the mambises, the liberation army fighting for independence from Spain and stayed in Cuba, where they became part of the Cuban working people.

You will often hear it said in Cuba that the Cuban nationality was forged one-third Spanish, one-third African, and one-third Chinese.

Chinese immigration to Cuba ebbed and flowed for a century. By the 1930s, the Barrio Chino in Havana was second in the Western Hemisphere only to San Francisco’s Chinatown in size and cultural life. It was the largest in all of Latin America.

As elsewhere, the Chinese population in Cuba rapidly became class-divided. It included peddlers, laborers, laundry workers and peasants. But by the 20th century there were also rich landlords, owners of department stores and large restaurants and clubs, bankers and others of great wealth. According to Cuba’s 1899 census, by that time there were 42 Chinese sugar plantation owners.

In the United States it’s not unusual to be told there are no longer any Chinese in Cuba, that “they all left with the victory of the revolution.” Like so much else said about Cuba in the U.S., that’s simply false. From 1959 to 1968 the plantation owners, bankers and well-to-do merchants — having tried and failed to save the U.S.-backed Batista dictatorship, or establish some other bourgeois regime — did flee the country. That’s true.

But tens of thousands of Cubans of Chinese descent were among the millions of Cubans who joined workers militias, drove organized crime out of Havana’s Chinatown, and repelled the U.S.-instigated invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. They and their descendants are everywhere in Cuba today, in all occupations. All you have to do is walk the streets of any city in Cuba to see the Chinese characteristics in face after face. The truth is obvious.

People’s Republic of China

I want to focus my remaining time on the main subject of my presentation here — some of the turning points in the political, economic and diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and Cuba over the last 60 years. And the different political and class starting points that have marked those relations.

When the revolutionary movement led by Fidel Castro took power at the opening of the 1960s, the new government immediately reached out to China. They identified with the victorious anti-imperialist struggles of the Chinese people that led to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In September 1960, Cuba became the first Latin America country to recognize what the capitalist rulers called “Red China,” defying Washington’s economic blackmail, which kept every other country in the Americas aligned for decades with Taiwan.

In a reciprocal way, as U.S. government attacks on the Cuban Revolution escalated, Beijing stepped in with assistance, much-needed shipments of rice above all. Before the revolution, most rice consumed in Cuba had been imported from the United States. That trade was abruptly ended in the early 1960s as part of Washington’s near-total cutoff of economic and financial relations with Cuba. China’s aid was greatly appreciated.

But the opening years of the Cuban Revolution also coincided with rapidly deepening divisions between the governments of China and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics — what became known as the Sino-Soviet conflict. The Cuban leadership led an impassioned political battle to convince both Moscow and Beijing to put aside factional interests and come together to support the Vietnamese national liberation struggle in face of the murderous war being waged by Washington and its imperialist allies. Che Guevara’s famous call in 1966 “to create two, three … many Vietnams” in solidarity with the Vietnamese struggle is well known.

In late 1965, in an effort by the Chinese government to pressure the Cuban leadership to line up with it as opposed to Moscow, Beijing abruptly slashed almost by half its emergency rice shipments to Cuba. Fidel Castro issued a scathing public response.

In a February 1966 statement published by Prensa Latina, Castro called the Chinese leadership’s action “a display of absolute contempt toward our country … and the dignity of our people.” In a public speech in Havana a month later, he said Chinese government officials had “introduced the style of absolute monarchies into contemporary socialist revolutions”; forgotten “the Marxist truth” that it is not individual men “but people who write history”; and made “a god of Mao Tse-tung.”

As the so-called Cultural Revolution unfolded in China in the late 1960s, the Cuban leadership was horrified by its destructive course; by its devastation of culture and education; and by its violent factionalism and adventurism, copied and practiced by pro-Maoist parties everywhere, including in Latin America.

Cuban leaders considered the factional divisions created by this Beijing-fostered course to be one of the factors that led to the defeat in 1967 of the Bolivian guerrilla front led by Che Guevara and to Che’s death in combat.

The Cultural Revolution played out with consequences in Cuba as well, as Chinese Cubans who backed the Mao leadership briefly gained control of the Chung Wah Casino in Havana, the main Chinese association in the country, before some of them abandoned revolutionary Cuba for the People’s Republic of China in 1968.

Although the two governments never broke diplomatic ties, relations between them had gone into a deep freeze by the last half of the ’60s, a situation that lasted for close to a quarter century. Those were years during which the governments of Cuba and the PRC confronted each other on opposite sides of the barricades in decisive international class battles.

Key among these clashes was the blood-drenched 1973 coup in Chile, after which Beijing developed close ties with the military dictatorship, including two state visits to the PRC by Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Other conflicts included Beijing’s 1979 invasion of Vietnam along its northern border, which was denounced by the Cuban government. And Cuba’s internationalist mission to help turn back the South African apartheid regime’s U.S.-backed invasions of Angola in the 1970s and ’80s, during which the Chinese regime aided counterrevolutionary Angolan forces aligned with Pretoria and Washington.

New relations open

A new stage of relations between the two governments opened at the end of the 1980s with the fall of the “meringue,” as Cuban President Fidel Castro called the collapse of regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe that had paraded as “socialist.” Virtually overnight, Cuba lost 85 percent of its foreign trade, bringing agriculture, industry, transportation and other economic activity to a crashing halt. The resulting economic and political crisis is known in Cuba as the Special Period.

These momentous shocks coincided with another watershed, the events of Tiananmen Square in spring 1989. In face of large youth mobilizations demanding political and economic reforms, the Chinese government declared martial law and used the People’s Liberation Army to put an end to the protests, killing countless numbers.

Amid the near-total isolation of Beijing internationally, the Cuban leadership supported the actions by the Chinese leadership. Fidel called them “regrettable” and said they were poorly handled, with inexperience perhaps, but that the Chinese leadership had no alternative.

In 1993, for the first time ever, the Chinese president, Jiang Zemin, visited Cuba, and Cuban President Fidel Castro reciprocated with a trip to China for the first time ever in 1995. The Chinese government also began providing vital emergency economic aid to Cuba. Even today, Cubans talk about the half million Chinese bicycles that became one of the most widely used means of transportation in those years. That welcome development was soon followed by a bicycle factory, built with Chinese equipment and aid, that was managed by the UJC, the Union of Communist Youth.

By some reports, the Chinese government extended over a billion dollars in loans to Cuba during the 1990s. Some of the interest and principal was later written down, as terms were renegotiated in 2011. But substantial yearly payments are still rigorously adhered to by the Cuban government.

As important as China’s aid to Cuba was, however, it pales in comparison with Chinese investments elsewhere in Latin America, including a reported $65 billion to Venezuela between 2005 and 2017. According to recent reports, China has announced plans to increase overall investments in Latin America to $250 billion by 2025.

Trade as a whole between Latin America and China amounts to roughly $260 billion a year today. Only $2 billion of that is with Cuba.

The point I want to emphasize, however, is that these trade ties and loans have nothing to do with international solidarity. They are strictly based on market relations and profit maximization for the lender. Investment in infrastructure projects like ports and railroads is everywhere tied to the purchase of Chinese equipment and materials and is financed in large part by loans to be paid in full and on time. That’s the basis of Beijing’s famous Belt and Road Initiative.

As Sío Wong was fond of saying, “Our Chinese friends don’t give anything to anyone.”

In the capitalist world, some academic “experts” on the Cuban Revolution gleefully, if inaccurately, joke that China has become “Cuba’s International Monetary Fund.”

Meanwhile, despite many signed memoranda of understanding with Beijing, pledges of cooperation and friendship, and reciprocal trade delegations back and forth, most major projects in Cuba have yet to materialize. That’s the case as of now with regard to funds to revitalize nickel production in eastern Cuba, modernize the oil refinery in Cienfuegos, and build luxury hotels and golf courses on prime real estate.

The policy of China’s leadership has been explicit throughout, to bring pressure to bear on the Cuban leadership to meet its international debt payments and to adopt China’s example of “market socialism.” It can more accurately be called “capitalism with Chinese characteristics,” if I can adapt a phrase from Deng Xiaoping.

End US economic war on Cuba!

Let me close on one point. The depth of the economic crisis facing Cuban toilers today is no secret to any of us. It’s severe.

As Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez told more than 1,000 participants at an international solidarity conference in Havana in early November, “I feel it is my duty to tell you that hard times are ahead of us.”

The brutally grinding and never-ending economic strangulation of the Cuban toilers by U.S. imperialism takes a heavy cumulative toll on a people whose “crime” is their refusal to become vassals of U.S. imperialism once again.

There are today in Cuba significant shortages of personal hygiene products, with the consequences we know that has for one’s dignity and sense of well-being. Diesel fuel, medicines, gas for cooking, as well as many food products are difficult to obtain.

And Washington is once again tightening the economic noose, seeking every way to choke off vitally needed imports and foreign currency. It’s an old story. We’ve all lost count how many times over the last 60 years, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, the pendulum has swung in this direction. In fact, most often the ratcheting up of economic pressure has been carried out under Democratic Party leadership.

If you follow the bourgeois media — whether “mass” or “social” — all you hear is that the difficulties facing Cuban working people are the inevitable result of six decades of efforts to advance along a socialist course in defiance of what capitalists consider to be “human nature” — that is, dog-eat-dog greed and exploitation.

Whatever mistakes and false steps have been made by the Cuban leadership — (and they are the first to acknowledge them) — it’s not hard to imagine what Cuba — once among the most economically developed countries of capitalist Latin America — would be like today if it had not been for Washington’s 60 years of economic strangulation. Cuba’s new guidelines for social and economic policy, adopted in 2011 after extensive nationwide debate, as well as the new constitution that went into effect earlier this year, are a recognition of the consequences of imperialism’s decadeslong war. The Cuban government has had to introduce greater space for market relations in Cuba. But the lesson is not the inevitable bankruptcy of socialism. It’s the opposite.

What emerges from this history is the capacity of working people in Cuba to make and defend their revolution since 1959 in face of this unrelenting assault by U.S. imperialism.

The surprise is not that they are forced to make a retreat. It’s the enduring example of what is possible when the working class and its allies take power, transforming themselves as they fight to transform the world.

I will end by quoting the words of Sío Wong at an ISSCO conference, like this one, that took place in Havana in 1999. In the pages of Our History Is Still Being Written, Sío Wong recounts an exchange he had at that event with ISSCO’s founding president, Wang Gungwu.

“How is it possible,” Wang asked Sío Wong, “that you, a descendant of Chinese, occupy a high government post, are a deputy in the National Assembly, and a general of the Armed Forces? How is that possible?”

Sío Wong answered: “The difference is that here a socialist revolution took place.” A revolution that eliminated the economic foundations on which discrimination based on the color of a person’s skin has been founded. A revolution that established a government that has been used by working people to fight all forms of discrimination and prejudice.

“To historians and others who want to study the question,” Sío Wong concluded, “I say that you have to understand that the Chinese community here in Cuba is different from Peru, Brazil, Argentina or Canada.

“And that difference is the triumph of a socialist revolution.”

That remains the lesson of Cuba for us today.