One of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for May is 50 Years of Covert Operations in the U.S. by Larry Seigle. It also includes “Imperialist War and the Working Class” by Farrell Dobbs, who was a central leader of the Socialist Workers Party and the Minneapolis Teamsters battles in the 1930s; and an introduction by Steve Clark. The excerpt is from the chapter “Origins of FBI Assault on Socialist Workers Party.” The book traces the decadeslong use of Washington’s political police against the unions, the SWP and other working-class organizations and struggles. At the end of the SWP’s 15-year lawsuit against the FBI in 1987, Judge Thomas Griesa ruled that their spying and disruption were unconstitutional. The book is a weapon for all working people in the fight to defend political rights. Copyright © 2014 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

For several years after the First World War, the FBI had functioned as a political police force, carrying out the arrest or deportation of some 3,000 unionists and political activists in 1919 and 1920 (the infamous “Palmer Raids”). But following widespread protests over these and other FBI actions, and with the decline of the postwar labor radicalization, the capitalist rulers decided against a federal secret police agency. They relied instead on city and state cops with well-established “bomb squads” and “radical units” and on state national guard units in cases of extreme necessity. These local and state agencies had intimate connections with antilabor “citizens” organizations organized by the employers and with hated private detective agencies, such as the Pinkertons, with long experience in union busting.

By the mid-1930s, however, a vast social movement was on the rise, with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) at the forefront. The relationship of forces was shifting in favor of working-class organizations. The bosses’ old methods could no longer always be counted on. Communist perspectives did not come close to commanding majority support among working people, and in fact remained the views of a small minority, but the bosses were nonetheless concerned that progressive anticapitalist and anti-imperialist political positions advanced by class-struggle-minded union leaders were winning a hearing among a substantial section of the ranks of labor. Especially in times of crisis, such as war, minority points of view defended by established and respected working-class fighters could rapidly gain support.

With this in mind, the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt expanded and centralized federal police power.

During and after the Watergate scandals of the mid-1970s, the immense scope of FBI disruption, spying, and provocations against the people of the United States came to light in an unprecedented way. But the origins of these operations are not — as most commentators place them — in the spread of McCarthyism in the 1950s or in Washington’s attempts to disrupt the anti-Vietnam War movement and social protests of the 1960s.

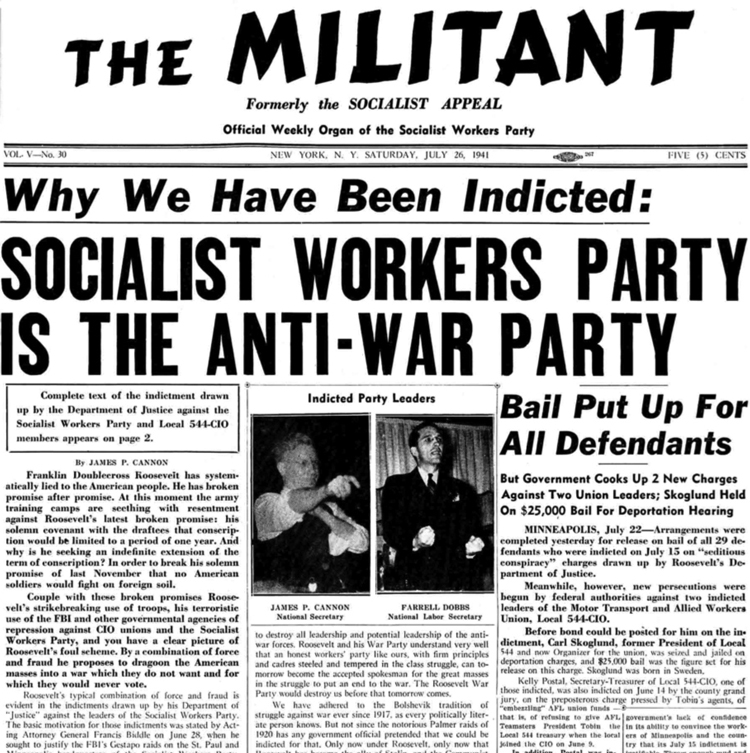

The fact is that these FBI operations began on the eve of the Second World War. They were central to preparations by the US capitalist rulers to lead the nation into another carnage to promote their interests against their imperialist rivals and against the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America struggling for liberation from colonial domination. These operations were directed against the leadership — and potential leadership — of the two major social forces in the United States that threatened to interfere with the ability of the US ruling families to accomplish their objectives: the labor unions and the Black movement. The government’s aim was to isolate class-struggle leaders who could provide guidance to a broader movement that might develop. …

The drive toward war necessitated an assault on working people at home and against democratic rights in general. Roosevelt gave FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover free rein to use the FBI against the labor movement and Black organizations. The White House and Justice Department secretly authorized many of the illegal methods used by the FBI and turned a blind eye toward others.

This authorization for the FBI to assume the functions of a political police force was done without legislation, which would have had to be proposed and debated in Congress. It was accomplished instead by “executive order,” a device that was rapidly assuming a major place in the operations of the government and would increasingly become a major mode of governing in the decades to come.

On September 6, 1939, Roosevelt issued an executive order directing the FBI “to take charge of investigative work” in matters relating to “espionage, counterespionage, sabotage, subversive activities and violations of the neutrality laws.” The key phrase was “subversive activities,” and the most important decision was to include this slippery concept in the list of responsibilities given the FBI. While there were federal laws against espionage, sabotage, and violation of US “neutrality,” no law explained what “subversive activity” might consist of.

Two days later Roosevelt — again by executive decree — made a “finding” of the existence of a “national emergency.” This allowed an increase in military spending without having to ask Congress for additional appropriations, thereby avoiding a sharpening public debate over the US government’s march toward war. Simultaneously, the president ordered an expansion of the FBI’s forces. His objective, Roosevelt told a news conference, was to avoid a repetition of “some of the things that happened” during World War I: “It is to guard against that, and against the spread by any foreign nation of propaganda in this country which would tend to be subversive — I believe that is the word — of our form of government.” …

The historical evolution of the FBI is part of a broader phenomenon in the United States. Underlying the threat today to the rights of privacy and freedom of association is the arbitrary rule by an expanding federal executive power. This power carries out policies at home and abroad that it is less and less able to openly proclaim or mobilize majority support for. It relies increasingly on covert methods to accomplish hidden or half-hidden objectives.