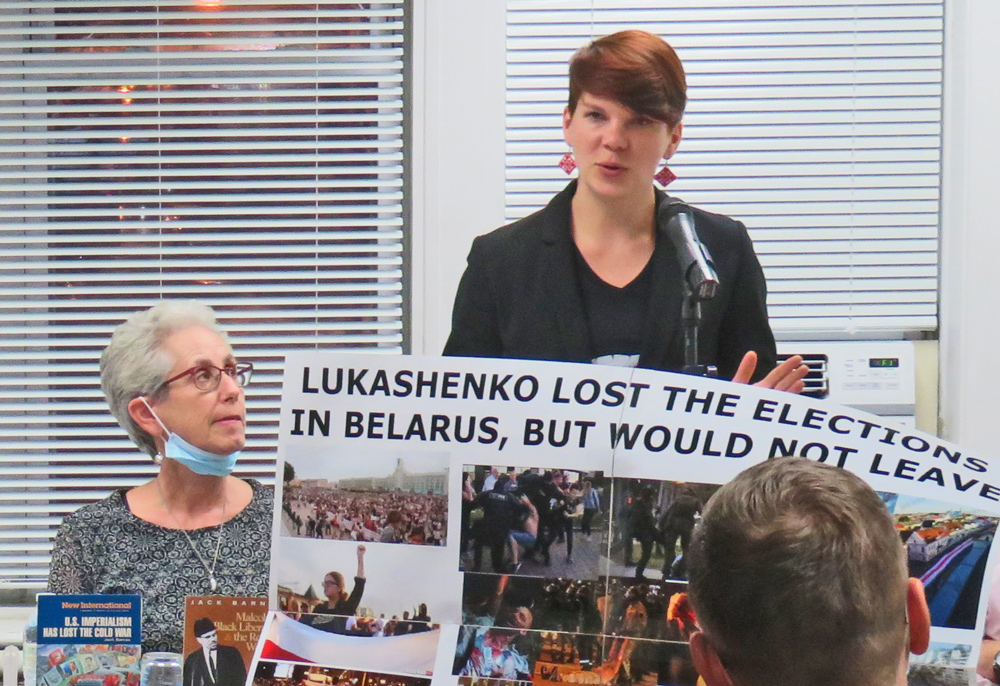

UNION CITY, N.J. — “I am here on political asylum. I was forced to leave because of repression in Belarus eight years ago,” Hanna Sharko, one of the leaders of Belarus Together, told a Militant Labor Forum here Sept. 26. Joanne Kuniansky, from the Socialist Workers Party, and John Studer, editor of the Militant, also spoke.

Sharko’s parents had received a threatening visit by the KGB, the secret police, after she wrote an article critical of the dictatorial regime of Alexander Lukashenko. “I am too young to remember any other president besides Lukashenko,” Sharko said, since the autocrat has held onto power for 26 years. In this year’s election, his government “suppressed the rival candidates,” then claimed “80% voted for him, when in fact 80% were protesting against him.”

“It is important for working people in the U.S. to support the protests to get rid of Lukashenko,” Kuniansky said. “We have common class enemies.” She noted that this capitalist ruler had called workers “sheep” with no right to participate in politics and claimed “women have no place in public affairs. But today we see them leading the protests.”

“One of the ways the Belarus government tries to control workers is through bonuses,” Kuniansky said, which for many make up almost half their wages. These payments can be “withheld if workers go on strike or otherwise oppose the government.”

“I led a Militant reporting team to Ukraine in 2014 when the working-class Maidan revolution brought down the regime,” Studer said. “We met and keep in touch with many fighters, coal miners, Crimean Tartars and others.”

The team also visited Chernobyl, the scene of the 1986 nuclear meltdown. “Some 70% of the radioactive fallout from Chernobyl fell on Belarus,” Studer said. “The Cuban government responded by organizing for over 25,000 children with cancers from Chernobyl to come for free medical care over decades.” This program “survived the collapse of the Soviet Union and Cuba’s Special Period” of extreme shortages, because the Cuban people saw it as their internationalist duty.

In the forum discussion, Aleksandr Khomchenko described Chernobyl’s “huge underlying impact on us, with so many getting sick or dying from it.” He said he worked in Belarus near the nuclear plant as an engineer for six months after the explosion. The government suppressed news of what had happened. But when he decided to protect his wife, who was pregnant, by leaving the area, he was told he had to turn in his Communist Party book. Khomchenko was blacklisted from any state employment after that, and left the country a few years later.

Studer said the Chernobyl disaster was a product of Stalinist disdain for working people, and the cover-up “helped strip bare people’s confidence in the government that supposedly represented working people.”

Sergei Yermak, another participant originally from Belarus, said that while Lukashenko once had popular support, today it has shrunk to 5% or 10% and “a new generation has appeared.”