One of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for March is Aldabonazo: Inside the Cuban Revolutionary Underground, 1952-58, a Participant’s Account by Armando Hart. He was a central organizer of the urban underground and one of the historic leaders of the Cuban Revolution. After overthrowing the U.S.-backed Batista dictatorship in 1959, Cuba’s toilers, led by Fidel Castro and the July 26 Movement, established a workers and farmers government and the first socialist revolution in the Americas. As minister of education, Hart helped lead the mass literacy campaign in 1961, which taught a million Cubans to read and write. He was minister of culture from 1976 to 1997. The excerpts are from the preface by editor Mary-Alice Waters. Copyright © 2004 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

BY MARY-ALICE WATERS

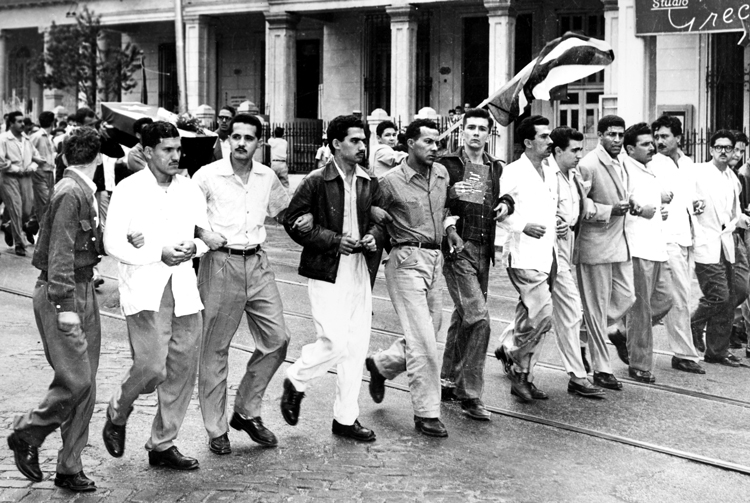

More than five decades ago, Armando Hart emerged as a leader of the young generation of students and working people who burst into history as they took to the streets in opposition to the 1952 military coup d’état in Cuba that installed one of the most brutal dictatorships Latin America had yet experienced. The Centennial Generation, as they became known, refused to accept or compromise with the tyranny and corruption that marked political life in Cuba. They asserted not only the right but the obligation of the Cuban people to rise in armed insurrection if need be to bring down a bloody, illegitimate regime that had usurped power by force. And they set out to forge a revolutionary movement capable of achieving their aims.

Aldabonazo — which in Spanish means a sharp, warning knock on the door — became a rallying cry of that generation of youth who risked their lives in defiance of the military regime. What distinguished them from the various bourgeois political parties and associations that opposed the Batista dictatorship was not primarily words, but deeds. Without fear of consequences for themselves, or political hesitation over where the struggle might lead, they fought for what they believed was right and refused to settle for less.

Fewer than seven years later, under the leadership of Fidel Castro, the July 26 Revolutionary Movement and its Rebel Army led the workers, peasants, and revolutionary-minded youth of Cuba to victory. Some 20,000 had paid with their lives by the time Batista and his henchmen fled the country on January 1, 1959. A new revolutionary government was installed with the jubilant support of the overwhelming majority of the Cuban people. Armando Hart was the first minister of education in that government.

Aldabonazo takes us into this history from the perspective of the cadres who with courage and audacity led the struggle waged by the urban underground. …

Through Hart’s account we begin to understand more fully and accurately the day-by-day political struggle waged by the forces that came together in 1955 under the leadership of Fidel Castro to form the July 26 Revolutionary Movement, named for the date of the 1953 assault on the Moncada military garrison in Santiago de Cuba that marked the opening of the popular insurrection against the dictatorship. We follow the men and women of the July 26 Movement as they work to develop their political program; as they struggle, through action and debate, to win the leadership of the revolutionary vanguard; as they take advantage of every opening to intervene in the broad political ferment, exposing the empty posturing and pretensions of the traditional bourgeois opposition parties; and as they clarify questions of strategy and tactics debated not only among the revolutionary cadres … but throughout the anti-Batista opposition.

Above all we come to appreciate the leadership capacities of Fidel Castro as he pulls together and politically orients the revolutionary cadres coming from diverse origins and experiences — exemplified by men and women like Armando Hart and his brother Enrique, Celia Sánchez, Frank País, Haydée Santamaría, Ñico López, Vilma Espín, and Faustino Pérez — to name but a few of those whom we meet and begin to know in these pages. We watch the core of the national leadership of the July 26 Movement in the Llano emerge, grow and recover from the blows of repression, and transform themselves in the course of the struggle. …

We see how the men and women of the July 26 Movement fought to forge a disciplined organization of cadres whose goal — as explained in the leadership’s 1957 “Circular No. 1 to the membership,” printed here — was “a) To overthrow Batista through popular action, [which] is not the same as just overthrowing him,” and “b) To consolidate the revolutionary instrument to ensure the fulfillment of the revolution’s program, also through popular action, [which] is not the same as simply creating a new party.”

Along this course the July 26 Movement and Rebel Army not only led the working people of Cuba to bring down the dictatorship and establish the first “free territory of the Americas.” They opened the road to the first socialist revolution in our hemisphere as well. For the first time since the Bolsheviks under Lenin led the workers, peasants, and soldiers of the tsarist empire to power in October 1917, a leadership of the toilers unpoisoned by the degeneration of the Russian Revolution emerged on the world stage, bypassing obstacles and creating new possibilities for struggle. A quarter century of revolution in the Americas ensued — from the Southern Cone through the Andes, to Central America and the Caribbean. The liberation of southern Africa became a reality.

Therein lies the root of the implacable hatred of the U.S. rulers for the Cuban Revolution and for those who led — and lead — it. Therein lie the reasons why for more than forty years Washington has never for an instant ceased attempting to punish the Cuban people for their audacity, to force them into submission. And why imperialism has failed. …

The Cuban Revolution in all its rich complexity is a vital, living part of the present and future struggles of Our America, and the world. The better we understand how that revolution was led to victory, the better prepared we will be to emulate its example and meet the challenges posed by the social and political explosions that will shape the twenty-first century.