DALLAS — Thousands of working people throughout Texas and neighboring states hit by a powerful snow and ice storm four weeks ago continue to face serious problems with lack of water, bankrupting-high utility bills, shortages of materials to repair broken water pipes, and food shortages at the grocery store.

The storm froze almost every source of energy in Texas, leading to widespread power and water outages for millions. Eighty people were counted as dead from the effects of the storm, but the full number won’t be known for weeks.

This social catastrophe was a product of the capitalist ruling families and their drive for profit above all else. They made sure that the energy industry in Texas would operate on this priority only.

Many are still impacted by the disaster. Clara Mendoza, who lives in the Vickery Meadow neighborhood in Northeast Dallas, told the Dallas Morning News that she was exhausted from the fight to find water. “Now we have water, but not hot water,” she said. She heats water for her family on the stove so they can wash and worries about how high her electricity bills will go.

Maria Magarin, who lives in the same complex, said her apartment is full of soggy carpet, the smell of mold and walls bulging from burst water pipes. Magarin, who has four children, said she went to the leasing office every day and they did nothing. After she threatened to call the police, they moved her family to another apartment.

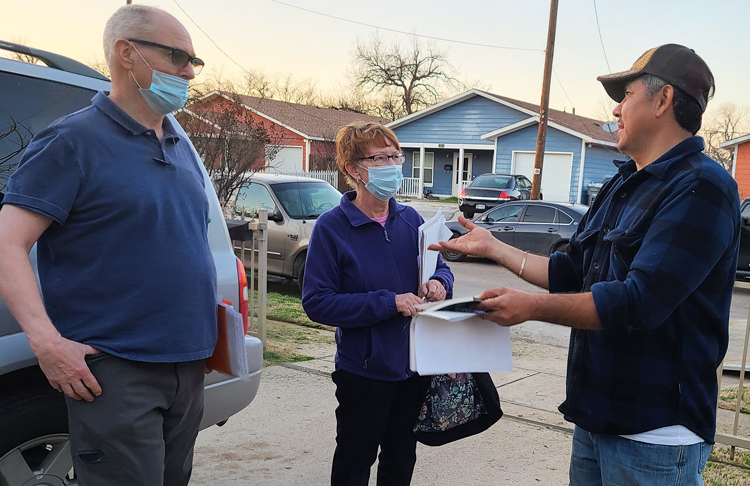

When supporters of Gerardo Sánchez, Socialist Workers Party candidate for City Council here, visited the Vickery Meadow neighborhood March 9 to express solidarity and discuss what workers can do, the apartment buildings still lacked water. Francisco Aben, a cleaner who lives in a nearby apartment complex, said that he and his wife were recovering from COVID-19 when the storm hit. With no income, they went 15 days without water. “When our rent bill came,” he said, “there was a charge on it for water, even though we had none.”

“We need our own party — a labor party based on the unions — to champion and lead a fight for the nationalization of the energy industry under workers control,” Sánchez said in a statement campaigners showed those they met. “Working people and our unions need to fight for a federally funded public works program to put millions to work at union-scale wages repairing broken pipes, damaged homes and apartment buildings, and replacing the worn-out power systems and other infrastructure in Texas and around the U.S.”

The majority of working people in Dallas rent in apartment complexes, where many are still recovering from broken pipes and storm damage. Dallas has the lowest homeownership rate of the top five most populous U.S. cities.

Rural areas were also hit extremely hard. Texas farmers and ranchers produce $25 billion in beef, dairy and vegetable products per year. Texas cabbages — 30% of the total U.S. supply — sweet onions, Valencia oranges, lemons and limes and other crops were either destroyed or severely damaged.

The livestock industry was hit by the storm with $228 million in losses. Water tanks froze, feedlots and dairies ran out of feed. Dairies and dairy farmers had to dump some 14 million gallons of milk.

These losses have pushed many farmers to the edge and led to food shortages at the grocery stores.

Working-class solidarity

There are many examples of working people coming to the aid of fellow workers as state and local officials left millions to fend for themselves. In Leander, small farmers gave away produce, meat and baked goods to their neighbors.

A coffee shop in Roanoke that lost electricity gave away milk to local families instead of throwing it out. “My four children were overjoyed,” one customer said. “We celebrated with cereal for dinner.”

“A lot of small towns are just destroyed right now. It’s bad. One grocery store supporting three or four towns. And without that, there’s just nothing,” Alyssa Young told KVUE-TV in Austin. Young, a dessert caterer, made sandwich kits and organized to have them taken to people in San Antonio.

“I lost power and my water meter froze,” Julio Moreno told SWP campaigners when they went knocking on doors in Dallas. He subscribed to the Militant newspaper.

“My next door neighbor helped me get the ice out of the frozen water meter and also gave me water,” he said. “My power came on but many houses on the block didn’t get it back, including my neighbor’s. We ran an extension cord from my house to his. He offered to help with the bill, but I said, you gave me water so we’re even.”

Moreno, an independent owner truck driver for short-haul deliveries for the printing industry, pointed to a transformer on the electrical line near his house. “They’re building more and more houses in the area and the transformers are too small for the neighborhood,” he said. “The companies don’t replace them and do the maintenance because they don’t want to spend the money.”

“This crisis was not a natural disaster, but was caused by the capitalist system that puts profits before human needs,” Sánchez said. “What working people did to aid each other is a small example of what we are capable of.

“The SWP campaign puts forward the perspective that working people can organize to come together and completely transform this society to meet the needs of humanity,” he said. “But this is only possible when we begin to fight and then realize what we are capable of. Then we can begin to build a powerful working-class movement to defend all those who are exploited and oppressed by the capitalist ruling families and organize in our millions to take political power into our own hands and establish a government of workers and farmers.”

George Chalmers contributed to this article.