Thirty-five years after a counterrevolutionary coup in 1987, a court in Burkina Faso, West Africa, rendered guilty verdicts April 6 after a six-month trial for the assassination of President Thomas Sankara, and 12 of his comrades and guards.

Blaise Compaore, along with his right-hand man Gen. Gilbert Diendere, and Hyacinthe Kafando, the soldier charged with leading the hit squad, were found guilty and sentenced to life in jail. Eight others were also found guilty and sentenced from three to 20 years in jail. Two had their sentences suspended. Three were acquitted.

Compaore, who lives in exile in neighboring Ivory Coast, and Kafando, who is on the run, were tried in absentia. Diendere is already serving jail time for a 2015 coup attempt. He and others charged in the assassination were present at the trial.

Sankara was 33 years old when he led a popular democratic revolution in 1983, one of the most profound revolutions in the history of the African continent. Compaore was a member of the National Council of the Revolution that Sankara led.

A popular revolution

With a population among the poorest in the world, the revolution led by Sankara opened the road to Burkina Faso’s development. Millions of toilers backed by the revolutionary government carried out deep-going economic and social measures.

These included nationalization of the land to guarantee peasants the fruit of their labors as productive farmers; irrigation projects; and planting 10 million trees to stop encroachment of the desert.

Steps were taken to combat the centuries-old subjugation of women. Three million children were vaccinated against common diseases. Far-reaching literacy campaigns were organized; roads, schools, housing and a national railroad were built.

Sankara’s revolutionary government extended international solidarity to those fighting oppression worldwide, including standing with the struggle against apartheid in South Africa and pointing to the example of Cuba’s socialist revolution.

“To achieve the new society,” Sankara said in an Aug. 4, 1987, speech celebrating the fourth anniversary of the revolution, “we need a new people, a people who have their own identity, a people who know what they want, who know how to assert themselves.

“After four years of revolution, our people have begun to forge themselves as this new people.”

With the murder of Sankara, Compaore unleashed a bloody counterrevolution, imposing his tyrannical rule. Gains of the revolution were reversed, and Burkina Faso’s government once again served the interests of the country’s exploiting classes and those of the French and U.S. imperialists.

Twenty-seven years later, in 2014, a popular uprising drove Compaore from power and millions of Burkinabe demanded “Justice for Sankara!” The government was finally forced to initiate legal proceedings demanded for 34 years by the Sankara family and the families of others murdered in the coup. The aim was justice, not revenge, Prosper Farama, a Sankara family lawyer, told the court.

The trial opened Oct. 11, 2021. It featured depositions and testimony from more than 100 witnesses and forensic experts and 20,000 pages of evidence.

“We had a real trial with ballistic experts and interventions on the facts: how people were killed, when, what happened in the months before Oct. 15 [1987] and after,” Anta Guisse, another Sankara family attorney, said in an interview with JusticeInfo. “The crimes were really premeditated.”

“Oct. 15 was meticulously prepared and skillfully orchestrated,” Boukary Kabore testified. “It was Compaore who “ran things with his civilian friends.”

Kabore, a military captain and Sankara supporter, led a battalion west of the capital city of Ouagadougou that was crushed in the coup. Eleven of its soldiers were executed by Compaore’s forces, who were fearful they would resist.

Damning evidence of betrayal

Evidence at trial included:

-

- Testimony that individuals who defended the revolution were targeted to be eliminated by Compaore’s coup plotters; and details of their arrests, imprisonment and torture;

- How Sankara’s murder had been planned and carried out, along with forensic evidence gathered from the exhumation of his and other bodies that had been dumped and buried in shallow graves on the outskirts of the capital city;

- Glimpses of information about the complicity in the coup of the French foreign intelligence service, the government of the Ivory Coast, and of the Libyan government of Muammar Gadhaji, despite court rulings to limit the proceedings to the charges against the accused.

Diendere and other defendants attempted to paint Sankara as the criminal, repeating false claims he conspired to have Compaore arrested.

Sankara was killed accidentally by Compaore’s personal guards, Diendere alleged, repeating the line peddled by Compaore after the assassination.

Trial testimony revealed how a slander campaign in the weeks leading up to the assassination was orchestrated by Sankara’s opponents and Compaore’s accomplices within the revolutionary government, vilifying Sankara and claiming he was power hungry.

“When I hear people say that Sankara’s death was an accident, I say no,” Blaise Sanou, a military officer at the time of the revolution, testified. “They planned his death and executed him.”

Other witnesses recalled how they informed Sankara of Compaore’s subversion and urged preemptive action, but Sankara refused. Sanou said Sankara would not allow himself to be drawn into factional political violence. “It is better to take one step with the people than to take 100 steps without the people,” Sanou said, paraphrasing Sankara.

“The one who was addicted to power was Blaise,” Sanou told the court. He noted how Compaore had other leaders of the revolution killed, and attempted to permanently hold on to power by rewriting the country’s constitution in 2014.

In the 1987 speech celebrating the revolution’s anniversary, Sankara warned, “We’ve been subjected to ever more slanderous attacks from both our traditional enemies and from elements springing from the ranks of the revolution itself; from impatient people infected with the dubious zeal of the novice, when it’s not from a frenzy of schemers with undisguised personal ambitions.”

An example for revolutionaries today

While the trial exposed many important facts about the murders, the courtroom could not serve as a place to draw the political lessons from the fight Sankara led to defend and advance the revolution. That task is in front of workers, peasants and young people today, and coming generations of revolutionists across Africa and worldwide. They will find invaluable lessons in the legacy of the Burkina Faso Revolution, as they seek to emulate Sankara’s example.

Sankara’s speeches and interviews over the four years the revolution held power are the place to start. They show his views and course of action, and provide insight into his leadership, integrity and selfless devotion to the emancipation of the oppressed and exploited worldwide from the “dog-eat-dog” values of the “capitalist jungle.”

Readers will find that Sankara opposed resolving political differences among the people and revolutionaries using violence and thuggery. He said those methods were a danger to the revolution.

In the fourth anniversary speech he gave in 1987, just weeks before his assassination, Sankara publicly expressed his determination to wage a political fight to keep the revolution on track. He insisted that the “revolution needs a convinced people, not a conquered people … not a submissive people passively enduring their fate.”

Sankara was a Marxist. He studied previous revolutionary struggles and saw the revolution he led as building on the continuity of earlier battles — from the American and French Revolutions at the end of the 18th century, to the Paris Commune of 1871, the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the Cuban Revolution of 1959. “We are the heirs of those revolutions,” he explained.

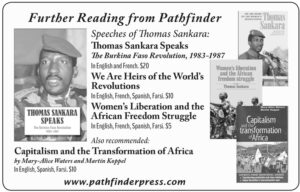

Readers can pick up a copy of Thomas Sankara Speaks, a collection published by Pathfinder Press, to learn more. See the ad on this page or visit distributors.