Reza Baraheni, a world-renowned leader in the fight for political and artistic freedom in Iran, died in Toronto March 24 at age 86. He was among that country’s most prominent poets, novelists and literary critics of the last half century.

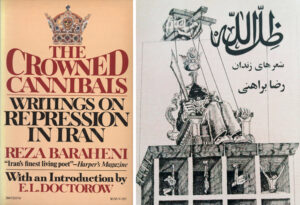

Among the more than 60 books written by Baraheni, in both Farsi (Iran’s official language) and English, are The Crowned Cannibals: Writings on Repression in Iran, his best-known collection of essays and poetry; God’s Shadow: Prison Poems; and the novel The Secrets of My Land. His translations into Farsi of works by others include Shakespeare’s Richard III and writings by Czech novelist Milan Kundera, Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, and revolutionary working-class leaders Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky.

Much has and will be written about these literary achievements, as well as his defense of free expression. This article focuses on the pivotal years in the 1970s and 1980s when his activity converged with Iranian youth and workers organizing not just to topple the Peacock Throne of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, but to advance the unfinished work of forging a revolutionary working-class party in Iran. Initiated in exile largely in the United States, this party-building activity extended into the years opened in 1979 by the Iranian Revolution.

Despite distortion by the shah’s regime and secret police (the Savak) of Baraheni’s political views and activity, intended to justify relentless persecution, he himself was never a member of any communist organization nor proponent of its program. He did, however, cultivate public ties of integrity and loyalty with proletarian revolutionists, who were among the most capable and selfless leaders and organizers of the defense of freedom of expression and association in Iran, North America and elsewhere, goals to which Baraheni committed a lifetime.

Fighting shah’s repression

Reza Baraheni was born in 1935 into an Azerbaijani Turk family in Tabriz, capital of East Azerbaijan province in northwest Iran. After university education in Tabriz and Istanbul in English literature, he took on teaching and administrative duties at the University of Tehran. In 1968 he was a founder of the Writers Association of Iran, whose demand for an end to censorship brought it into collision with the shah’s enforcers.

After teaching in Texas and Utah in 1972-73, Baraheni returned to Tehran and published an article entitled “The Culture of the Oppressor, and the Culture of the Oppressed.” He was already known for defense of his native Azerbaijani language and the tongues of other oppressed minorities, which were banned from being taught in Iranian schools. With Persians comprising some 60% of Iran’s population, the monarch — one of the “crowned cannibals,” in Baraheni’s words — anointed himself “Shah of Shahs” of the Persian nation. He brooked no resistance by Azerbaijanis (16% of the population), Kurds (10%), or Baluchis, Arabs, Turkmen and the rest.

On Sept. 11, 1973, Baraheni was arrested, interrogated about his recent article, and confined and tortured at Comité prison for 102 days. An international campaign demanding his release, including a letter in the New York Times signed by 35 prominent artists, writers, and political figures, won his freedom in January 1974. Baraheni went into exile in North America.

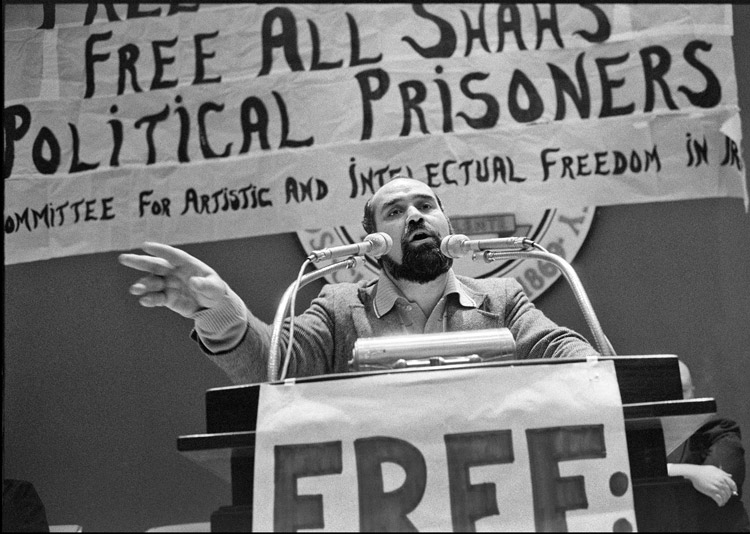

“I came to the United States with the intention of exposing the Shah’s repression,” he wrote in an account of his captivity in The Crowned Cannibals. “I immediately joined the ranks of Americans and Iranians who had formed the Committee for Artistic and Intellectual Freedom in Iran (CAIFI), which had been instrumental in releasing me from the Shah’s jail.”

CAIFI had been founded in late 1973 to conduct the campaign to free Baraheni. Over the next half decade, it defended numerous targets of the shah’s regime, helping win the release of writers Ali Shariatti, Gholamhossein Sa’edi and others. Baraheni became CAIFI’s honorary co-chair and most prominent spokesperson.

The committee’s central initiators were Iranian students in the U.S., as well as George Novack and other Socialist Workers Party leaders (see box). Since the 1960s, members of the SWP and Young Socialist Alliance had joined with Iranian students and others to organize protests — in Los Angeles, New York and Washington, D.C. — whenever the shah traveled here to do the bidding of his chief underwriter and arms supplier, the U.S. imperialist government.

CAIFI organized well-publicized defense meetings in cities, towns, and on campuses across the U.S., at many of which Baraheni spoke and read his poetry, sharing the platform with other well-known individuals. These events were frequently met with provocations and disruptions by thugs from ultraleft Maoist Iranian student organizations, sometimes wielding nail-studded clubs, knives and other weapons.

These Stalinist groups slandered Baraheni and CAIFI leaders as agents of the shah. Meanwhile, actual Savak agents, with FBI and CIA aid and comfort, were also hurling smears and death threats against Baraheni. Many writers, artists and other CAIFI endorsers signed letters condemning these attacks on freedom of speech and assembly.

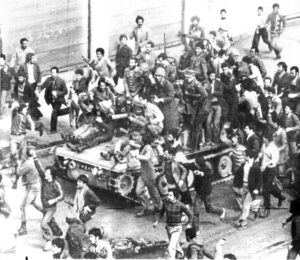

Baraheni and other CAIFI leaders were not silenced by these assaults. By 1978 their effective exposure of the shah’s tyranny and resounding demands for cultural and political freedom were converging with rising street actions, strikes and other mass protests in Iran itself.

Struggle for a proletarian party

Many young Iranian opponents of the shah in the U.S. joined the Socialist Workers Party and gained valuable experience and education in communist politics, proletarian propaganda activity, and mass work. In the mid-1970s, in collaboration with the SWP, they established an Iranian organization in exile, named by them the Sattar League.1

They produced a magazine, Payam Daneshjoo, and established the Fanus Publishing House to make available in Farsi basic Marxist works, which members of the new organization circulated widely. These books included The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Transitional Program for Socialist Revolution and The Young Lenin by Leon Trotsky — each translated into Farsi by Baraheni — as well as titles on the fight against national oppression, for women’s emancipation, and the working-class line of march toward the conquest of power.

Several weeks prior to the revolutionary overturn of the shah’s regime on Feb. 11, 1979, this initial cadre returned to Iran. Just hours after landing in Tehran, at a Jan. 22 news conference widely covered by the Iranian and world press, they announced the founding of a proletarian party, the Hezbe Kargaran Socialist (HKS/Socialist Workers Party). The organization was renamed the Workers Unity Party (HVK) in January 1981, after a couple of years of class-struggle experience, political debate and leadership clarification and realignment.2

Baraheni, who had flown back to Tehran with HKS leaders, opened the press conference, saying that although he was not a party member, “full freedom of speech and expression must be restored in the press and in culture and literature.” There should be free elections, he said, with all associations and political parties able to contest for support.

The party’s program for working people in Iran was presented by HKS leaders Babak Zahraie, Mahmoud Sayrafiezadeh and Parvin Najafi. They called for the Iranian people’s participation in decision-making through the democratic election of a constituent assembly. Pointing to the October 1917 Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia and the January 1959 mass insurrection and general strike in Cuba, Sayrafiezadeh said that working people in both revolutions had learned “it was not enough to overthrow a dictatorial regime. It was necessary to continue the struggle until power was wrested from the ruling class and a workers and peasants government established.

“This will also be true in Iran,” he said. “A socialist revolution is necessary.”

Members of the new party — those returning from exile, as well as workers, soldiers and students who soon joined — were active on many fronts of the class struggle. They were workers in oil and petrochemical refineries, garment and textile plants, and other industrial workplaces. They were militants in factory shoras, councils set up by workers to combat capitalist sabotage and the bosses’ speedup, assaults on job safety, and low or often unpaid wages.

The HKS called for land distribution under control of peasant shoras, as well as national self-determination and language rights of Kurds and other oppressed peoples. They joined with women workers fighting for equal pay for equal work, child care and against compulsory veiling or any other degrading treatment.

From the outset, there was repression by the new bourgeois government, as forces loyal to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini sought to play on the cleric’s influence as a decadeslong opponent in exile of the shah. Their aim was to consolidate a Shiite-based bourgeois-clerical regime, in order to stem and reverse advances of the revolution.

The balance of class forces between working people and the oppressed, on the one hand, and what was soon ratified as the Islamic Republic, on the other, shifted with stops and starts for nearly four years.

The HKS’ first public meeting, held March 2, was assaulted by gangs of both Islamist and Maoist thugs. Brandishing switchblades and chains, the attackers bellowed smears of Baraheni and HKS leaders, who were at the meeting. More than 2,000 people had turned out, including delegations of cement workers, workers from the General Motors and Iran National auto plants, teachers, students, rail workers and others. Although marshals prevented the goon squads from provoking a bloody clash, meeting organizers suspended the event and launched a public campaign demanding enforcement of the right to assemble and carry out political activity.

Less than a week later, tens of thousands of women, workers, and youth took to the streets of Tehran and other cities on International Women’s Day to push back Khomeini’s initial decree that female government employees be compelled to wear veils and other traditional clothing to work. Demonstrators defended themselves in face of government-instigated attackers, forcing the regime not only to back off for a period of time but also to concede to women in factories and other workplaces the right to participate and hold office in workers’ shoras.

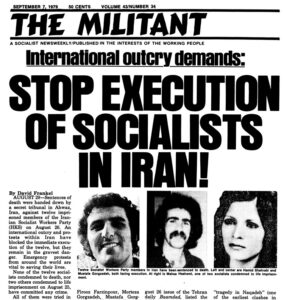

In August 1979 a secret tribunal in oil-rich Khuzestan province handed down death sentences to 12 HKS members and life terms to two others. The government refused to announce charges. In fact, the only “crime” of the arrested militants was popularizing the HKS’ revolutionary working-class views among workers — many from Iran’s Arab national minority — in the region’s oilfields, refineries, steel mills and elsewhere. By April 1980 an international defense campaign, among whose signers in Iran was Reza Baraheni, had won freedom for all fourteen.

The HKS ran 17 candidates in the August 1979 Constitutional Assembly elections, including three of its imprisoned members (Mustafa Gorgzadeh, Mahsa Hashemi, and Hamid Shahrabi), as well as the only soldier running for the Islamic Republic’s so-called Assembly of Experts (Nourik Aghazian). In the January 1980 election for president of Iran, the HKS ran Mahmoud Sayrafiezadeh. And in March 1980 the party fielded eight candidates for Iran’s national parliament.

In September 1980 the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein launched a full-scale invasion of Iran, with tacit backing and arming by Washington, Paris and other imperialist powers. Working people in Iran responded to the war as a bid to deal a deathblow to the revolution. Members of the new party were among hundreds of thousands of working people who volunteered to serve and fight on the front. This mobilization against the Iraqi regime’s reactionary attack gave a second wind to popular resistance to the counterrevolution at home.

Baraheni arrested, then fired

In October 1981 Baraheni, who had resumed teaching at the University of Tehran, was picked up by police as he left campus. He was secretly held and interrogated for 84 days, with no charges or news of his whereabouts. Baraheni again won his freedom due to an international defense campaign, in which those who had founded the new party in Iran took an active part.

Baraheni was fired from his university teaching job, however. Refusing to be either gagged or caged, he helped convene a clandestine meeting of the banned Writers’ Association in 1994. Baraheni joined with other members in drafting and signing a declaration — the Text of 134 — calling for “freedom of expression, without limits or exceptions.” He translated the manifesto into English and organized to smuggle the manifesto out of Iran to the well-known U.S. playwright Arthur Miller, and Miller read it to delegates at the 1994 Prague Congress of PEN International, the worldwide writers’ association.

With the secret police again on his heels, Baraheni evaded border guards and by 1997 took refuge in Canada. Settling in Toronto, he resumed his writing and teaching for as long as his health allowed, serving as president of PEN Canada from 2001 to 2003.

When Reza Baraheni’s death was announced by his family in March, no condolences were forthcoming from the London-based Iranian monarchist TV network Manoto, which broadcasts to concealed satellite dishes across Iran. Baraheni “had 43 years to say he’d made a mistake,” wrote a commentator, “and he could have apologized to the Iranian people, but he preferred to leave this world as a traitor.”

A traitor to the crowned cannibals of capital the world over, yes. And proud he was of being so. But not to the fight for freedom of speech and expression to which he devoted his life.

* * *

By the end of 1982, an escalating government offensive of arrests, executions, and thug terror in Iran made it impossible for revolutionary-minded workers to any longer organize and build a proletarian party there.

Some 35 years later, however, ever since the close of 2017, those who produce the wealth depended on by Iran’s rulers to sustain their profits and comforts have begun to display mounting defiance of the bourgeois-clerical regime and all its wings.

Working people in cities, small towns and rural areas — oil and petrochemical workers; sugar workers and teachers; small farmers; Persians, Arabs, Kurds, Azeris and others; young and old; women and men — have time and again taken to the streets in their thousands and tens of thousands. They’ve demanded unpaid wages, water rights, affordable fuel prices, dignity for women and oppressed nationalities, and the freedom to speak their minds, organize and act in their own class interests.

Above all, more and more workers, farmers, and their families are sick and tired of Tehran’s counterrevolutionary wars waged to serve Iranian capital’s expansionist aims. They want no more military adventures, stretching from the Afghan border, across Iraq, Syria, and the Arabian peninsula to Lebanon’s Mediterranean shores. No more body bags and funerals. No more enforced sacrifice at working people’s expense and the rulers’ enrichment.

In a congratulatory message to the Hezbe Kargaran Socialist in January 1979, Socialist Workers Party National Secretary Jack Barnes hailed the party’s founding as “an historic and inspiring event,” one prepared through “patient propaganda” and “painstaking tasks.”

From the assembling of a cadre in North America and Iran almost half a century ago, through today’s social crises and mobilizations, the patient and painstaking effort to translate, keep in print, and distribute the programmatic lessons working people need has never stopped. It continues in the growing catalog of books produced by Talaye Porsoo and other publishing houses in Iran. It continues in the wide circulation of those publications, including two translated by Reza Baraheni, in bookshops, stalls at the Tehran International Book Fair, among students and within the working class.

That work continues to this day.

1 Named after Sattar Khan, a central leader from the Azerbaijani region of the 1905-11 Constitutional Revolution in Iran.

2 See “Communism, the Working Class, and the Anti-Imperialist Struggle: Lessons from the Iran-Iraq War,” two HVK documents, with an introduction by Samad Sharif. Printed in no. 7 of New International, a magazine of Marxist politics and theory published and distributed by Pathfinder Press.