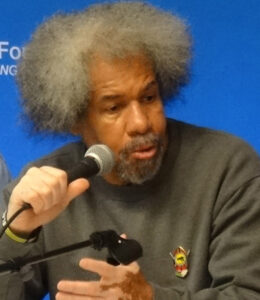

Albert Woodfox, a former Black Panther who emerged from nearly 44 years in solitary confinement as still a determined political fighter, died Aug. 4. He was 75.

Released from jail in 2016, Woodfox published a book, Solitary: My Story of Transformation and Hope, and toured the U.S. and worldwide, speaking out against the savagery of the U.S. “justice” system and calling for an end to solitary confinement, a brutal punishment used to torture 75,000 prisoners in the U.S. today.

Woodfox was open in his book about his youth. As a teenager in 1965, he was convicted for a series of petty crimes and sent to Angola, a notoriously racist prison in Louisiana. After his release, he was arrested again and convicted for armed robbery. “I stole from people who had almost nothing, my people, Black people,” he said.

The turning point for him came in 1969 after he escaped from a courtroom and fled to New York, where he was caught and sent to “The Tombs” prison in Manhattan. There he met members of the Black Panther Party, who organized political discussions, treating people respectfully and intelligently.

“It was as if a light went on in a room inside me that I hadn’t known existed,” he wrote. “I had morals, principles and values I never had before.”

He was sent back to Angola in 1971, where he helped set up a prison chapter of the Panthers with fellow inmates Herman Wallace and Robert King. “We were concerned with oppressed people,” he told the Militant after his release, “not just oppressed Blacks and Hispanics.” At the time Angola prison was segregated. “The one area where Blacks and whites were allowed altogether was in sports. “We came over with the idea that we could have football games and use that to communicate with each other.”

Their political activities did not go unnoticed by the prison authorities. When prison guard Brent Miller was stabbed to death in a cell in 1972, prison officials framed Woodfox and Wallace for the killing, even though they knew neither man had anything to do with it.

“They pinned it on us, because we were militants,” King told the Militant after Wallace’s death. “We wanted to bring consciousness to our fellow prisoners that we are protected by due process, the 14th Amendment and other constitutional grounds.”

King was framed up by prison officials and convicted of killing a fellow inmate in 1973.

Together they became known as the Angola Three, and opponents of injustice and prison brutality worldwide fought for their release. They spent decades in solitary confinement.

To confront their conditions, “we turned toward society, not away,” Woodfox wrote. He became a voracious reader, reading everyone, including Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. “These books helped shape and change my way of looking at the world,” he said. Woodfox studied law to be better able to fight and help others.

He organized games played up and down the line of solitary cells by shouting down the tier or banging on pipes — a way they held math tests and quizzes about Black history. Woodfox took special pride in helping several other prisoners learn how to read. “Our cells were meant to be death chambers but we turned them into schools, into debate halls,” he told the press.

King was released after his conviction was overturned in 2001. Wallace died in October 2013, three days after he was released. Over the course of four decades, Woodfox’s conviction was overturned three times.

After being released, Woodfox went on tour in 2019. “They say this system is democracy. Really it’s all about class warfare,” he told people. “They have perfected a way to get people to fight against their own interests. This economic system divides everyone by race, gender, class and sexual orientation.”

At every speaking engagement Woodfox urged audiences to join in calling for an end to solitary confinement.

When back home in New Orleans, he enjoyed time with his daughter, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and with his partner, Leslie George.

He remained an optimist to the end. “I have hope for humankind,” he wrote in his book. “It is my hope that a new human being will evolve so that needless pain and suffering, poverty, exploitation, racism, and injustice will be things of the past.”