Our book feature this week is FBI on Trial: The Victory in the Socialist Workers Party Suit Against Government Spying. Readers will find it of special interest in light of the latest assault on constitutional rights by the Biden administration authorizing an armed FBI raid on former President Donald Trump’s Florida residence Aug. 8. Ten days earlier federal prosecutors in Florida sent FBI agents to raid the homes of Black rights groups Uhuru and the African People’s Socialist Party in Florida and Missouri.

The excerpt from FBI on Trial contains federal court proceedings from the 1973-88 political and legal battle waged and won by the Socialist Workers Party and Young Socialist Alliance against decades of spying, harassment and disruption by the FBI and other federal agencies. This campaign helped educate millions about class “justice” under capitalism.

The FBI was tasked as the capitalist rulers’ political police in the late 1930s as the Democratic administration of Franklin Roosevelt drove to take Washington into the second world imperialist war. Roosevelt signed into law the thought-control Smith Act and launched FBI raids and federal prosecutions against the SWP and leaders of the Teamsters union in the Midwest, seeking to silence their campaign for labor opposition to Washington’s war aims.

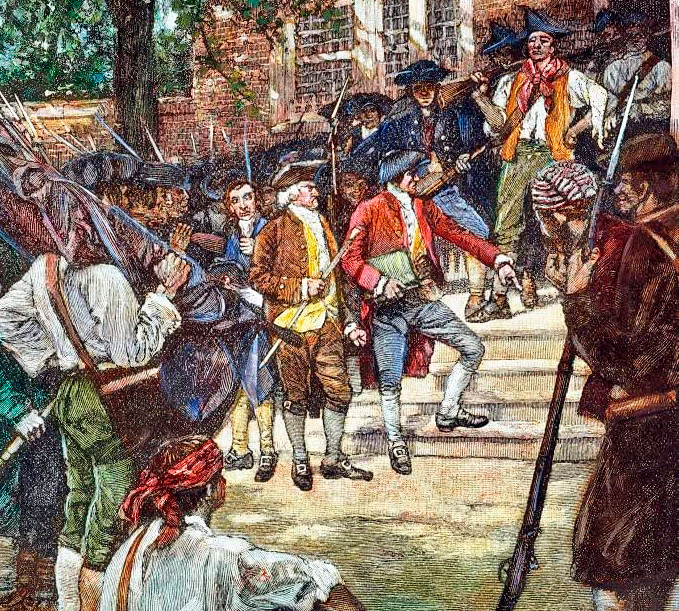

Freedom of speech and assembly, as well as protection from unreasonable search and seizure, are rights conquered in the American Revolution, registered in the Constitution, and extended by struggles of working people since. The use of these rights by millions in hard-fought class battles has been integral to building unions, organizing opposition to Washington’s wars, bringing down Jim Crow segregation and fighting for women’s emancipation.

The excerpt is from the testimony by Jack Barnes, national secretary of the SWP, at the close of the 1981 trial of the party’s lawsuit, which had been underway for three months. Barnes was questioned by Margaret Winter, chief counsel for the SWP. FBI on Trial also contains excerpts from the testimony of Farrell Dobbs, Barnes’ predecessor as national secretary, who in the 1930s was the central leader of the Teamsters organizing drive and anti-war campaign mentioned above.

Copyright © 1988 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

* * *

Margaret Winter: Mr. Barnes, I hand you the copies of the Constitution of the United States and the Declaration of Independence.

Does the Socialist Workers Party believe that their ideas are consistent with the philosophy underlying the United States Constitution?

Jack Barnes: Yes, in the sense that a republican form of government — in the sense of a rule of law, which has elected officials that govern — is the only possible basis for socialist democracy, for the extension of democracy, as counterposed to any authoritarian and totalitarian mode of functioning.

That philosophy is similar to the philosophy of those who held that in the writing of the Constitution.

I leave aside the complexities. There were big differences among the framers of the Constitution.

I am especially saying yes in the sense of taking the Constitution as amended with the Bill of Rights, with the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments, the amendments on the franchise, on the poll tax and so forth, all of which substantially in our opinion democratize the Constitution. Some took mighty struggles. Three took a civil war of the most horrible kind to accomplish.

Without an extension of those conquests all talk about socialism is a mockery.

But the answer has to also be no in this sense. The Constitution was written with the philosophy which did not see a contradiction between the republican forms and checks and balances of the Constitution and chattel slavery for millions of human beings; for property requirements for the electorate; for the lack of franchise for more than half the population, the female half, until the twentieth century; for no rights for the original native residents of the continent; the original absence of the Bill of Rights itself; the absence of even direct elections of senators; and a number of things like that.

But to that degree the philosophy is in contradiction completely with the philosophy of Marxism, which would define a workers’ and farmers’ republic, our concept of democracy, as being combined in a constitution which would be in contradiction to chattel slavery, property requirements, restriction of franchise for any reason of sex or age or anything like that. It would also include the fact that the prerogatives of the largest property owners, the largest productive property owners, the owners of the big mines, mills, and factories would be subordinate to the development and extension of the democratic rights of the great majority of the citizenry.

In some ways maybe the Civil War is the best example of this — the blood that was necessary to eliminate chattel slavery and get the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments. But the fact that it took until 1964 to get the poll tax to be unconstitutional [the 24th Amendment to the Constitution] and 1965 to, by law [the federal Voting Rights Act], guarantee the franchise without any restrictions because of anything to do with color to the adult citizens of the American South —

Judge Griesa: Look, I respect those views, you know. I mean we are really not here debating about slavery or anything like that and let’s bring this to a close.

Barnes: All right.

The yes and no can be indicated maybe in one other thing. That’s the evolution toward greater and greater concentration of executive power, which has been a tremendous change since the drafting of the Constitution and the original first ten amendments. We feel there is a growing contradiction from even the constitutional viewpoint — talking politically, not as a lawyer — between executive decision, orders, even up to a declaration of war and the total protections guaranteed by the amendments to the Constitution.