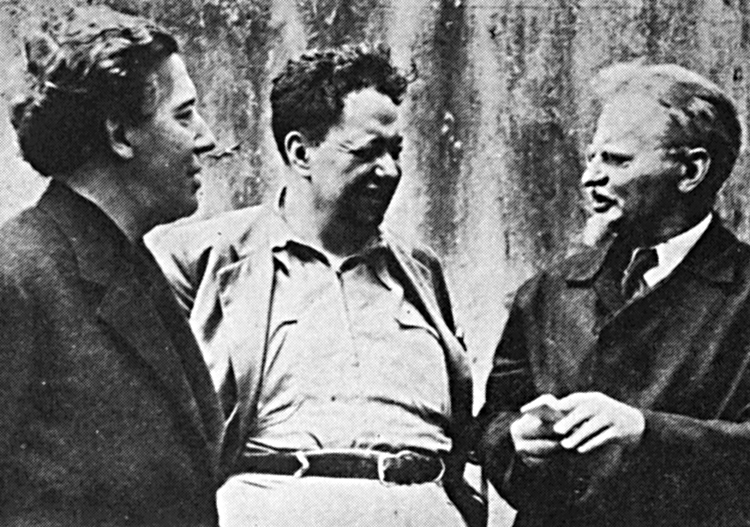

What Is Surrealism? Selected Writings by André Breton, is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for January. Breton was the founder and major leader of the surrealist movement, one of the most influential currents of 20th century art and art criticism. The excerpt is from “Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art,” which was written by Breton, revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky and artist Diego Rivera when the three met together in Mexico in 1938. Copyright © 1978. Reprinted by permission of Pathfinder.

We can say without exaggeration that never has civilisation been menaced so seriously as today. The Vandals, with instruments which were barbarous and comparatively ineffective, blotted out the culture of antiquity in one corner of Europe. But today we see world civilisation, united in its historic destiny, reeling under the blows of reactionary forces armed with the entire arsenal of modern technology. We are by no means thinking only of the world war that draws near. Even in times of ‘peace’ the position of art and science has become absolutely intolerable.

In so far as it originates with an individual, in so far as it brings into play subjective talents to create something which brings about an objective enriching of culture, any philosophical, sociological, scientific or artistic discovery seems to be the fruit of a precious chance; that is to say, the manifestation, more or less spontaneous, of necessity. Such creations cannot be slighted, whether from the standpoint of general knowledge (which interprets the existing world) or of revolutionary knowledge (which, the better to change the world, requires an exact analysis of the laws which govern its movement). Specifically, we cannot remain indifferent to the intellectual conditions under which creative activity takes place; nor should we fail to pay all respect to those particular laws which govern intellectual creation.

In the contemporary world we must recognise the ever more widespread destruction of those conditions under which intellectual creation is possible. From this follows of necessity an increasingly manifest degradation not only of the work of art but also of the specifically ‘artistic’ personality. The regime of Hitler, now that it has rid Germany of all those artists whose work expressed the slightest sympathy for liberty, however superficial, has reduced those who still consent to take up pen or brush to the status of domestic servants of the regime, whose task it is to glorify it on order, according to the worst possible aesthetic conventions. If reports may be believed, it is the same in the Soviet Union, where Thermidorian reaction is now reaching its climax.

It goes without saying that we do not identify ourselves with the currently fashionable catchword, ‘Neither fascism nor communism!’ — a shibboleth which suits the temperament of the philistine, conservative and frightened, clinging to the tattered remnants of the ‘democratic’ past. True art, which is not content to play variations on ready-made models but rather insists on expressing the inner needs of man and of mankind in its time — true art is unable not to be revolutionary, not to aspire to a complete and radical reconstruction of society. This it must do, were it only to deliver intellectual creation from the chains which bind it, and to allow all mankind to raise itself to those heights which only isolated geniuses have achieved in the past. We recognise that only the social revolution can sweep clean the path for a new culture. If, however, we reject all solidarity with the bureaucracy now in control of the Soviet Union, it is precisely because, in our eyes, it represents not communism but its most treacherous and dangerous enemy.

The totalitarian regime of the USSR, working through the so-called cultural organisations it controls in other countries, has spread over the entire world a deep twilight hostile to every sort of spiritual value; a twilight of filth and blood in which, disguised as intellectuals and artists, those men steep themselves who have made of servility a career, of lying-for-pay a custom, and of the palliation of crime a source of pleasure. The official art of Stalinism, with a blatancy unexampled in history, mirrors their efforts to put a good face on their mercenary profession.

The repugnance which this shameful negation of principles of art inspires in the artistic world — a negation which even slave states have never dared to carry so far — should give rise to an active, uncompromising condemnation. The opposition of writers and artists is one of the forces which can usefully contribute to the discrediting and overthrow of regimes that are destroying, along with the right of the proletariat to aspire to a better world, every sentiment of nobility and even of human dignity.

The communist revolution is not afraid of art. It realises that the role of the artist in a decadent capitalist society is determined by the conflict between the individual and various social forms which are hostile to him. This fact alone, in so far as he is conscious of it, makes the artist the natural ally of revolution. … The need for emancipation felt by the individual spirit has only to follow its natural course to be led to mingle its stream with this primeval necessity — the need for the emancipation of man.

The conception of the writer’s function which the young Marx worked out is worth recalling. ‘The writer’, he said, ‘naturally must make money in order to live and write, but he should not under any circumstances live and write in order to make money . . . The writer by no means looks on his work as a means. It is an end in itself and so little a means in the eyes of himself and of others that if necessary he sacrifices his existence to the existence of his work . . . The first condition of freedom of the press is that it is not a business activity.’

It is more than ever fitting to use this statement against those who would regiment intellectual activity in the direction of ends foreign to itself and prescribe, in the guise of so-called reasons of state, the themes of art. The free choice of these themes and the absence of all restrictions on the range of his exploitations — these are possessions which the artist has a right to claim as inalienable. …

Our aims:

The independence of art — for the revolution.

The revolution — for the complete liberation of art!