NEW YORK — Nov. 30 and Dec. 8, 2021, marked the 80th anniversary of the Nazi execution by firing squad of 25,000 Jews in the Rumbula Forest outside Riga, Latvia. It was the beginning of the Holocaust in that Baltic country, and came two months after a similar massacre of 30,000 Jews at the Babyn Yar ravine in Kyiv, Ukraine, and similar Nazi atrocities against Jews across Europe.

Of Latvia’s 94,000 Jews before the Nazi invasion of July 1941, only a few thousand survived the war.

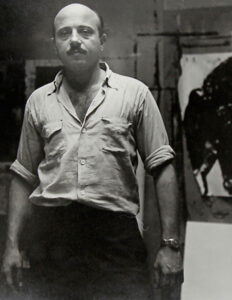

One of them was Boris Lurie, an artist who witnessed his mother, sister, grandmother and girlfriend being rounded up for Rumbula. There they were forced to undress and then were shot by Waffen-SS executioners.

For the first time Lurie has an exhibition of his early artwork of the 1940s based on his experience of the Holocaust after he and his father, who also survived in German forced labor camps, emigrated here. “Boris Lurie: Nothing to Do But to Try,” is at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. Due to the unexpectedly large response, the museum has extended the exhibit until Nov. 6. It was originally scheduled to close April 29.

The exhibition of his paintings and drawings of Nazi camp life, portraits of his mother and self-portraits, family photographs and samples of his writings make for a powerful testament by a Holocaust survivor. Boris Lurie in Riga: A Memoir, which Lurie wrote in 1976, is available at the museum and serves as a catalogue for the show.

Boris Ilyich Lurie was born in Leningrad, Soviet Russia, July 18, 1924, to a Belarusian Jewish family from the Pale of Settlement, an area where Jews were allowed to live under the pogrom-ridden czarist regime. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution transformed everything, granting citizenship to all Jews, including the Luries. His mother, Shaina Chashkina Lurie, was a dentist and socialist Zionist; his father, Ilya, a businessman dealing in leather and other commodities.

The revolution liberated the Baltic States from the “prison house of nations” that was czarist Russia. In 1926 Ilya and Shaina moved the Lurie family to Riga, capital of the now independent Latvia. Lurie’s father pursued logging, lumber and other businesses. His mother set up a dentistry practice.

From the historic influence of past colonial domination of the Baltics, Lurie’s education was in German, and he also learned Latvian and English. These languages later served him well. His first language was always Russian, and he spoke English with a marked accent.

His remembrances of life in Riga as a boy and youth in the 1930s, and then in German slave labor camps in Latvia, Poland and Germany, are recounted in his Boris Lurie in Riga. Written after Lurie’s visit to Riga in 1975, going back for the first time since 1944, it is a searing account of his experience in the Holocaust — the Riga slave-labor ghetto; the Lenta, Salaspils and Kaiserwald camps outside Riga; Stutthof near Danzig in Poland; and finally Buchenwald-Magdeburg in Germany, where he was liberated April 18, 1945, by U.S. troops.

On Nov. 30, 1941, and again on Dec. 8, women, children, men who stayed with their families, and elderly men were marched from the German-created Riga ghetto to the execution grounds in Rumbula Forest, seven miles out of town. There they were marched to trenches dug in the soil and shot by German SS troops.

With the Stalin-Hitler pact dividing up Poland and the Baltic States between Nazi and Soviet occupation, Riga was under Soviet rule from June 1940 until July 1941, when the Nazi army invaded Latvia. As a 16-year-old, Lurie was impressed by the might of the Red Army. “We believed in Soviet invincibility,” he wrote. But then, “in a week’s time it is over, I see German motorized columns… . The Red Army is no more, as if disappeared by a magic wand.”

Some Jews — “the lucky ones” — were able to retreat with it to the east and survived. Several thousand served and most died in the Latvian Division during the Siege of Moscow.

But the vast majority of the 40,000 Jews of Riga were caught up and herded into two ghettos. Lurie’s mother, sensing what was going to happen to the Jews, made the fateful decision to divide the family. She, her own mother, and daughter Josephina remained in the ghetto, while Lurie and his father went to the Arbeitslager Work Camp for those able-bodied men destined to toil in slave-labor camps. The women all perished in the Rumbula Forest slaughter.

After liberation from the Buchenwald-Magdeburg slave-labor camp, Lurie used his knowledge of English and German to get a job with the U.S. Army. This in turn provided an avenue for him and his father to come to New York, where his surviving sister had been during the war.

Searing portraits of Holocaust

It was then that Lurie began to relive the Holocaust in the series of paintings, drawings and photographs that are “Nothing to Do But to Try,” a phrase he wrote about struggling to create art out of his Holocaust experience. Among the paintings in the exhibition are the haunting image of Shaina Lurie, “Portrait of My Mother Before Shooting,” and “Roll Call in Concentration Camp.”

In a 1950 letter to the New York Times, Lurie wrote, “It will hardly be remembered, except unfortunately by a very few, that December 8th stands for anything but the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor. As Japanese planes dropped their first loads on the American base, 25,000 Jewish children, women and old people were being murdered.”

Like at Babyn Yar in Ukraine, there was no memorial to the massacre there. It was only when a group of Jews in 1963 put up a canvas at the forest, titled “The Jew,” with arm upraised, that there was any recognition of what had transpired. Local authorities took it down. Instead, they put up a generic stone monument with words in Latvian, Russian and Yiddish, just reading “To the victims of fascism,” with a hammer and sickle.

No mention of the fact that the victims were Jews. It was only in 2002 that a monument — a large menorah sculpture surrounded by hundreds of stones with the names of some who perished — was erected, making clear the massacre of the Jews there was part of the Holocaust.

The paintings and other materials in the exhibit are a powerful reflection of what befell Jews under Nazi rule. Any escape from the slaughter was cut off by the capitalist rulers in the U.S. and England, who closed their borders to the Jews.

Lurie’s later work

Not included in the exhibition is Lurie’s later work. He died in 2008. In the 1950s he founded the NO!art group, which rejected art as a commodity. Lurie was promoted in Europe by the art historian and collector Arturo Schwarz, who was drawn to a life in art when, as a teenager in Alexandria, Egypt, he read the “Manifesto: Towards a Free Revolutionary Art” written by Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, surrealist André Breton and Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Inspired by the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, Lurie and his life-long friend and sculptor, Rocco Armento, got in Armento’s wreck of a car and drove from New York to Miami in 1959 and caught the overnight ferry to Havana to see it for themselves.

Fifty-eight years later the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Habana put on a retrospective of Lurie’s later work, “Boris Lurie in Habana.” Included was his painting, “Mort Aux Juifs (Israel Imperialiste),” (Death to the Jews, Israel Is Imperialist), Lurie’s protest against an anti-Semitic slogan attributed to Fatah, the Palestinian organization.

Fidel Castro, central leader of the Cuban Revolution, understood the horror of the Holocaust and defended the right of Israel to exist as a refuge for Jews. “The Jews have lived an existence that is much harder than ours,” he told Jeffrey Goldberg from Atlantic magazine in 2010. “There is nothing that compares to the Holocaust.”

When Goldberg asked Castro if he thought the state of Israel had a right to exist, Castro said, “Yes, without a doubt.”

I strongly recommend Militant readers see the exhibition.

Arthur Hughes, a long-time member and supporter of the Socialist Workers Party and a volunteer on the Militant staff, knew and worked with Boris Lurie.