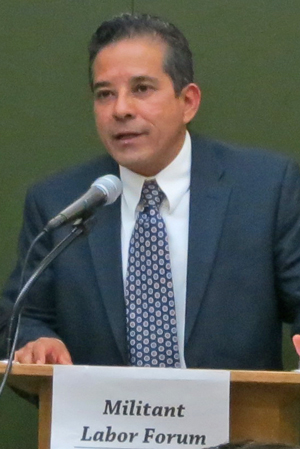

NEW YORK — Although Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega still drapes himself in the symbols of the 1979 Sandinista Revolution, the government he heads is a capitalist government, Socialist Workers Party leader Róger Calero told participants at the Militant Labor Forum here Aug. 4.

Ortega was elected president in 2006, 16 years after the ruling Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN), Ortega’s party, was voted out of office. That electoral defeat was a registration that the FSLN had ceased being a revolutionary party, explained Calero. Well before that election took place, the government headed by Ortega and the FSLN was no longer a workers and farmers government and the FSLN had become a bourgeois party. Its policies today are a continuation of the pro-capitalist course it adopted in the late 1980s.

“Since April 19 when FSLN supporters attacked senior citizens protesting cuts in social security, tens of thousands of people — largely working-class — have gone out in the streets to demand the end of government repression and the resignation of Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo,” Calero noted. Calero and Maggie Trowe, SWP candidates respectively for governor and U.S. Senate from New York, were on a fact-finding tour in Nicaragua for several days in May.

The attacks on protesters by police and paramilitaries have left at least 300 dead, hundreds wounded, hundreds more in jail and have spurred further protests.

Workers and farmers take power

Workers and farmers in Nicaragua did more than remove the brutal, corrupt U.S.-backed dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza on July 19, 1979. “They set out on an anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist course,” Calero said. “Their struggle was guided by the political program and strategy charted by Carlos Fonseca — the central leader of the FSLN until his death in 1976 — and Nicaraguan workers and youth who were inspired to emulate the Cuban Revolution.

“They understood that the entire bourgeois apparatus and repressive army needed to be brought down and replaced with a popular government,” he said. “And that could only be done through mass mobilizations around a political program advancing the interests of working people.”

In the first years of the revolution, the FSLN and the new workers and farmers government began carrying out that program. “It encouraged the formation of unions,” Calero said. “It expropriated land, factories and other properties belonging to the Somoza family and those close to it. It replaced Somoza’s army with a popular army and police born out of the militia and guerrilla units that fought in the 1979 insurrection.

“It began a land reform and mobilized tens of thousands of workers, peasants and youth from the city and countryside to carry out social programs that benefited the worst-off sections of the working class,” he said. “Women fighting for equality made gains. Before the revolution, for example, women and minors working as agricultural workers were not paid their wages directly. The head of their household received it. Women won the right to be paid directly and to be included in titles for land distributed by the revolution.

“In 1980 the revolutionary government launched a literacy campaign modeled on the one in revolutionary Cuba,” he said. “Some 90,000 youth and workers went into the countryside to teach peasants to read and write, forging a link between rural and urban toilers. To this day, it’s hard to find someone who was not transformed by that experience.”

When Calero was a student in Managua during the revolution, “the teacher assigned us to bring in news clippings on national liberation movements,” he said. “That’s how I learned about the fight for independence for Puerto Rico and other struggles.”

The revolution had a worldwide impact, including in the United States. Pointing to Nicaragua and the revolution in the Caribbean island of Grenada earlier in the year, Fidel Castro said that together with Cuba they were “three giants rising up to defend their independence, sovereignty, and justice, on the very threshold of imperialism.”

‘Militant’ Managua bureau

Within days of the July 19 victory, the Socialist Workers Party set up a bureau of the Militant in Managua. The party and the bureau stayed there for more than 11 years, reporting on the rise and decline of the revolution for workers around the world.

“The party helped organized tours of Nicaraguan trade union and FSLN leaders to speak in the U.S., and trips to Nicaragua so that trade unionists, small farmers and youth from the U.S. could do the same,” Calero said.

From the beginning, the U.S. government looked for ways to undermine and destroy the revolution. It financed and trained a counterrevolutionary army, which launched a bloody war against the workers and farmers government.

The land reforms from the early days of the revolution had stalled, leading to anger from many peasants. This aided the contras. Nonetheless, the workers and peasants were able to defeat the U.S.-led contra war.

FSLN turned back on program

But by the mid-1980s FSLN leaders began to retreat from their revolutionary course. “They rejected the example set by the Cuban Revolution and its leadership of building a communist party rooted in the working class and a government built on an alliance with small farmers,” Calero said.

“Instead of mobilizing workers and peasants to deepen the fight against capitalist exploitation, they sought alliances with Nicaragua’s capitalists,” Calero said. In 1989 President Ortega announced that the government was not going to confiscate “one more inch” of land from so-called “patriotic producers,” a euphemism for landlords and capitalists who remained.

After their 1990 electoral loss, the FSLN leadership, before handing over office to the new government, distributed among themselves state-owned farms, land, businesses and homes. Many became part of the capitalist class in the process.

Over the next decades much of the land that had been distributed to landless peasants has ended up back in the hands of big capitalist landowners, as they are driven off the land by the normal workings of capitalism.

The reconcentration of land has continued under the Ortega government. A far-fetched plan for a transcontinental canal through Nicaragua, Calero explained, has become a vehicle for pushing more peasants off the land. Leaders of the peasant movement against the 2013 law approving the canal have been harassed and jailed over the years. Most recently, the government jailed peasant leader Medardo Mairena under “terrorism” frame-up charges stemming from his role in the protests since April.

Today’s FSLN government is a capitalist government, “a Bonapartist regime,” Calero said. “It pretends to rule above classes and serve as an arbiter between workers and bosses” but in reality it is subordinate to the capitalist class.

“The policies implemented since 2006 were not the whim of Ortega and Murillo, his wife and vice president,” Calero noted. “They were policies supported by the main capitalist associations and families” and were considered acceptable by Washington and capitalist investors. By focusing on “Ortega” as the problem, or the “presidential couple,” capitalist sections who are part of the opposition — including those who had been in alliance with Ortega and switched sides when the protests exploded — and other political parties try to hide the fact that the problems facing working people in Nicaragua are the result of capitalism.

“There are different class forces involved — workers and farmers who are fighting for rights and better conditions, and capitalists who want to keep their system of exploitation intact, but without the baggage of Ortega, whose growing unpopularity has made him a liability for them.”

Some on the left who defend the government claim that Washington is behind the protests. “While there is no question that U.S. agencies have funneled funds to opposition groups,” Calero said, “that’s not the reason for the massive protests.”

Countless programs organized and financed by Washington to overthrow the Cuban Revolution since its triumph in 1959 have failed, Calero said, because workers and farmers have confidence in what they see as their own revolution and leadership. “The FSLN government has dug its own hole with its anti-working-class policies and course.”

Many of the protesters, Calero said, are workers who were part of the 1979 revolution and their sons and daughters who have heard the stories about the transformation their parents went through. “They reject what the FSLN has become,” Calero said, “but have not drawn the lessons of why the revolution was lost.” There is no party or organization in Nicaragua today that is fighting to get back to the working-class course laid out by Fonseca.

Contra war took tremendous toll

SWP leader Mary-Alice Waters noted during the discussion period that the U.S.-backed counterrevolutionary war took a tremendous toll — some 30,000 dead out of a population of just 3.5 million at the time. The war went on for five years.

The Cuban government did everything it could to aid the Nicaraguan and Grenadian revolutions, Waters said. Against their strong advice, the FSLN-led government instituted the military draft in 1983. “The Cubans explained that you can’t win a revolutionary war with a conscript army,” Waters said.

During his presentation Calero had noted the impact of the FSLN’s retreat from deepening the land reform. “Peasants and rural workers were alienated by the lack of response to their demand for land.”

“After taking power, the Cuban revolutionary leadership immediately implemented the most sweeping land reform. They decisively ‘crossed the Rubicon,’ winning the support of the peasantry,” Waters said. “The FSLN didn’t do that in Nicaragua.” In 1989, 10 years after the insurrection, there were 60,000 landless peasant families, while the best land was still in the hands of big capitalist farmers and ranchers.

Calero encouraged participants to read New International magazine no. 9 on “The Rise and Fall of the Nicaraguan Revolution,” which was written in the midst of the struggle. That is “a good place to start” to get a better understanding of the evolution of the government headed by Ortega and the road forward to advance the interests of working people.

“The worldwide economic and social crisis of capitalism is deepening,” Calero said. Workers and peasants in Nicaragua will be part of struggles through which they can build a revolutionary leadership in the years ahead.