The article below by Marta Rojas Rodríguez, a veteran Cuban revolutionary, journalist and writer, was run in Granma July 25. In July 1953, Rojas, then a 25-year-old journalism student, covered the trial of Fidel Castro and other revolutionaries who had attacked the Batista dictatorship’s Moncada army garrison in Santiago de Cuba. She wrote an eyewitness report for Bohemia but the magazine didn’t publish it, for fear of government reprisals, until after the revolution triumphed on Jan. 1, 1959. Rojas’ books and articles on these and other historical events are well known in Cuba. The excerpts give a vivid description of the Cuban revolutionaries who attacked Moncada. Translation is by the Militant.

BY MARTA ROJAS RODRÍGUEZ

The fact that the Cuban people were politically prepared and full of patriotic fervor in 1953 is shown by the social composition of the revolutionary movement that the young attorney, Fidel Castro Ruz, was able to pull together following the military coup of March 10, 1952, carried out by Fulgencio Batista, and promptly recognized by the Yankee government.

The members of what would become a transformative, revolutionary movement knew how to size up the critical moment in which they were living. They reflected the conception of the people that Fidel would later define in his defense statement following the Moncada assault known as “History will absolve me.”

It was among the majority of Cubans — peasants, workers, unpretentious professionals, unemployed youth and those with temporary and seasonal jobs — that the spark of the true revolution was lit. The insurgents were not only audacious. They understood and wanted to achieve more than a simple change of government.

The organization’s program was outlined by Fidel. Part was spelled out in the 1940 Constitution, suspended by Batista during the coup. Among other provisions, it abolished large estates or excessively large land holdings, but laws to implement this were never approved. Fidel’s proposal included this as a fundamental point, in addition to rejecting domination by U.S. companies such as the United Fruit Company, and all kinds of companies, including the electric, telephone and gasoline companies.

Also among its fundamental elements were the development of public education, a health care program that would reach the entire people, and many other social demands that were made reality after the Jan. 1, 1959, triumph of the revolution. …

Without a doubt the number of illiterates was growing in the 1950s, and education and health care were of little concern to the governments of the moment. But political culture, in the most advanced sense of the term, finally won out in our society, thanks to the patriotic tradition.

It’s enough to look at the social origins of a number of the July 26 combatants who died, the majority murdered, and some of the survivors. This is a representative list. Fidel was able to recruit more than 1,000, most of whom later joined the July 26th Movement and carried out heroic tasks, joining the list of heroes and martyrs. They represent, as he said, the people of Cuba, if you are talking about struggle.

The brothers Horacio and Wilfredo Matheu Orihuela, and Remberto Abad Alemán Rodríguez, bricklayers, masonry workers; Lázaro Hernández Arroyo, Pedro Véliz Hernández, Armando Mestre Martínez, Tomás Álvarez Breto, and Juan Almeida Bosque, bricklayers; Rafael Freyre and Hugo Camejo, tile workers; Flores Betancourt Rodríguez, worker in gem cutting shop; Pablo Agüero Guedes, bricklayer assistant; Emilio Hernández Cruz and Manuel Saiz Sánchez, carpenters; Armando del Valle López and Juan Domínguez, furniture builders, woodworkers; René Bedia, house painter.

Alfredo Concha Cinta, Manuel Isla Pérez, Marcos Martí Rodríguez, Carmelo Noa Gil, Manuel Rojo, Gerardo Antonio Álvarez, José Labrador, and Ismael Ricondo — all peasants or farmworkers.

José Luís Tasende de las Muñecas (cell leader), and Vicente Vázquez, refrigeration mechanics; Juan Manuel Ameijeiras, Mario Martínez Ararás, drivers; Francisco Costa Velásquez, drivers assistant; Jacinto García Espinosa and Antonio Betancourt Flores, longshoremen; Virginio and Manuel Gómez, cooks (working at the Belén Jesuit School); José Ramón Martínez, leather tanner; José de Jesús Madera, laborer; Félix Rivero Vasallo, bartender; Pablo Cartas Rodríguez, restaurant worker; Andrés Valdés Fuentes, baker; Ángel Guerra García, sheet metal worker; Pedro Marrero worked in a brewery; Víctor Escalona, shoemaker.

Abel Santamaría Cuadrado, employed in a major commercial office and a student, as was Boris Luís Santa Coloma, also a trade union leader; Julio Reyes, bank worker; Oscar Alcalde, owner of a pharmaceutical laboratory; Ramón Méndez Capote and Elpidio Sosa, traveling salesmen; Miguel Oramas, worker and photographer, like Fernando Chenart Piña; Raúl de Aguiar, student; Raúl Gómez García, teacher, poet, and trade union leader; Renato Guitart Rosell, shipping agent at his father’s company; Julio Trigo, student and traveling medicine salesman; Oscar Alberto Ortega, store clerk; Gildo Fleitas student and professor, as well as office worker; Guillermo Granados and Roberto Mederos Rodríguez, commerce workers; Rigoberto Cocho, electrical worker; Gregorio Careaga, funeral home worker; Ciro Redondo, employee, traveling salesman; Ramiro Valdés, employee, like Pepe (José) Suárez, principal cell leader in Artemisa. With a few exceptions, all were members of the Orthodox Party or youth group in their hometowns.

The unemployed, or marginally employed, must also be added, including Osvaldo Socarrás and Humberto Valdés Casañas, who were day workers, earning just enough to eat as car parkers; or Giraldo Córdoba Cardín, who was making a debut as a boxer; Rolando San Román, occasional oyster salesman and José Testa Zaragoza, who sold flowers.

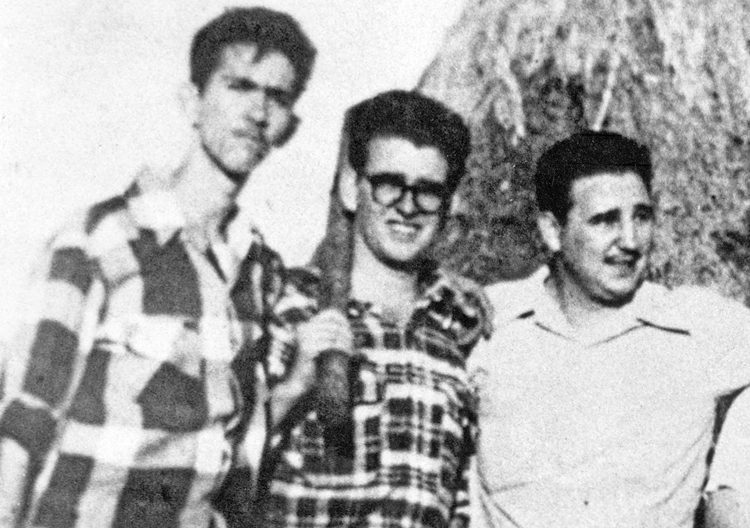

Antonio Ñico López was a vendor in a Havana agricultural market. He survived, went into exile in Guatemala, and was the first of the revolutionaries to meet the young doctor Ernesto Che Guevara, who he later introduced to Fidel and Raúl. It was from Ñico that Che learned the ins and outs of the organization and about the assaults on the Moncada and Bayamo garrisons.

Others who must be mentioned to complete the picture of “the people, when it comes to struggle,” as Fidel said during his trial — Pedro Miret, engineering student; Raúl Castro, student; Mario Muñoz, doctor; Haydée Santamaría, self-taught and a homemaker; Melba Hernández Rodríguez del Rey, practicing lawyer, as was Fidel Castro Ruz.

All — mentioned or not — were imbued with knowledge of history, from the independence heroes to the most contemporary. They knew, and this was shown during the trials, about the value of the sugar workers leader, Jesús Menéndez, who Abel especially admired, since he had worked in the former Constancia mill in Villa Clara, where the Santamaría family lived. Abel, Haydée’s brother, was the second in command of the Movement of the Centennial Generation. He was captured and vilely murdered in the Moncada Garrison.